article continued…

History of MDMA

3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (or MDMA) was first synthesized from an extract of sassafras by Anton Kollisch, a German chemist working for Merck. On December 24, 1912, Merck filed two patents on the molecule under the name “methylsafrylaminc.”36

Although both Merck and the United States Army experimented with the molecule – mainly in the 1950s – it was not until the mid-1970s that MDMA’s psychotherapeutic potential was first glimpsed. In search of an alternative to 3,4-methylenedioxy-amphetamine (MDA), which was made illegal in 1970 by the CSA, the American chemist Alexander T. Shulgin began tinkering in his laboratory. Shulgin re-synthesized MDMA and, in 1978, co-published a paper with David Nichols on the molecule’s psychoactive properties. Appreciative of the benign, heart-opening, and non-hallucinatory properties of MDMA, Shuglin referred to the drug as his “low-cal martini” and passed it on to psychotherapists like Leo Zeff, PhD (AKA “The Secret Chief”), and Shulgin’s own wife, Anne, a Jungian psychologist who is celebrated to this day as the matriarch of the psychedelic movement. The use of MDMA spread to other therapists, who used the substance with their clients as a therapeutic “lubricant,” especially within the context of couples’ therapy.37-39

Like many consciousness-enhancing substances, MDMA held value not only therapeutically, but also recreationally: in the 1980s MDMA (or “Ecstasy”) became popular in the techno dance cultures of the United States and United Kingdom.

At the same time, the crack cocaine epidemic was ravaging inner cities of the USA, and the Reagan Administration was keen to respond. Nancy Reagan launched her Just Say No campaign, and the Drug Abuse Resistance Education (DARE) program was launched.40,41 (Curiously, a meta-analysis from 2004 concluded “that D.A.R.E. is ineffective,” and a 2009 meta-analysis of 20 controlled studies revealed that those who attended the DARE program were just as likely to abuse drugs as those who had no intervention.42,43)

In 1985, MDMA was added to Schedule I, in a move perhaps akin to throwing away the proverbial baby with the bathwater (the baby being MDMA; the bathwater crack cocaine). The American psychotherapist Rick Doblin, PhD, sued the DEA in an attempt to block the total criminalization of MDMA. Many witnesses testified in support of the molecule, including psychiatrists who spoke of the drug’s compelling therapeutic applications. Doblin won: DEA law judge Francis Young ruled that MDMA should be classified as a drug with a moderate to low potential for physical and psychological dependence, available prescription-only – and ergo placed in Schedule III. (Other drugs in Schedule III include acetaminophen with codeine, testosterone, and ketamine.44) Young’s recommendation was rejected by the head of the DEA, however, and MDMA was categorized as a Schedule I drug.45,46

In 1986, Doblin created the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS), an organization that has since fought to encourage more research on MDMA and other psychedelic compounds.47

Nineteen eighty-six (1986) also marks the year in which the Anti-Drug Abuse Act was passed. The law, which was signed by Reagan, substantially increased the number of drug offenses (including those related to cannabis) with mandatory minimum sentencing. This zero-tolerance policy directly contributed to an increase in nonviolent drug arrests and higher rates of incarceration in America. The Act instituted a five-year minimum sentence – without parole – for those convicted of possessing either five grams of crack cocaine (a drug more commonly used by poor Americans, in particular, poor, inner city-dwelling Blacks) or 500 grams of powder cocaine (an expensive preparation more commonly used by affluent Caucasians). This penalty disparity of 100:1 has been criticized as inherently racist. Regardless of the intention, the Anti-Drug Abuse Act certainly affected the Black community more adversely than the White: Prior to the enactment of the Act, African Americans were subject to 11% higher federal sentences for drug possession/sales than Whites; by 1990, that rate swelled to 49%.48

The War on Drugs did not stop the personal and recreational use of psychedelic substances so much as it drove it underground. What the War did do, however, was thwart decades of research – research that the medical community desperately needed, given the alarming rate at which depression and other mental illnesses have been steadily climbing (even pre-pandemic).49 The criminalization of psycho-spiritual medicines like psilocybin, LSD-25, and MDMA did to psychological research what kinking a hose does to the flow of water.50

Water Returns to the Well: The Psychedelic Renaissance

Due to the persistent efforts of groups like MAPS and the Beckley Foundation, the generous donations from private parties like Tim Ferris, the courage of clinicians and researchers willing to risk it all, and a robust awareness-raising campaign (sweeping from the Joe Rogan podcast to Michael Pollan’s two most recent books), we are once again able to research these unique molecules and consider their therapeutic applications.

After a lull of decades, in 1998, researchers led by Franz X. Vollenweider, PhD, at the University of Zurich published the first post-Drug War study on psilocybin,51,52 effectively cracking the seal on a new generation of psychedelic research. Since then, Vollenweider has authored or co-authored over 90 studies on psychedelic compounds.53

In 2000, researchers at Johns Hopkins University obtained regulatory approval to research the effects of psychedelics in healthy volunteers. Psilocybin studies were followed by research focused on LSD-25.54 Research into ayahuasca, MDMA, and other entheogenic substances quickly followed: Scientifically robust studies on psychedelics are now easy to find in PubMed. Most of the current studies are funded by non-profit organizations like Johns Hopkins’ Center for Psychedelic and Consciousness Research (CPCR), the Centre for Psychedelic Research at the Imperial College of London, the Beckley Foundation, and MAPS. A newcomer to the effort is the Center for Neuroscience of Psychedelics at Massachusetts General Hospital, the original teaching hospital of Harvard Medical School.

What was once a choked garden hose is now a steady stream of science.

Psychedelic compounds have been shown to effectively help with a variety of ailments, including depression,55-57 treatment-resistant PTSD,58 social anxiety in those on the autism spectrum,59 eating disorders,60 obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD),61 anxiety in those with terminal illness,62 and Parkinson’s disease.63 Psychedelics have also shown promise in the treatment of various drug addictions,64 including nicotine,65 opioids,66 alcohol,67 methamphetamine,68 and crack cocaine addictions.69 (Note: the references peppering this paragraph are far from an exhaustive list of indications or studies.)

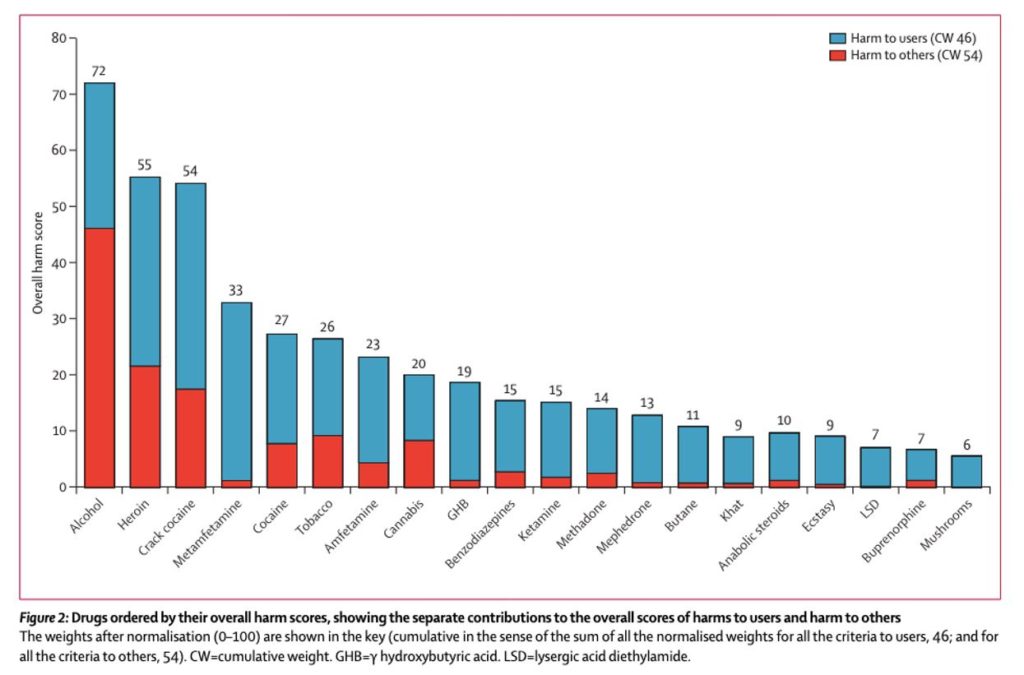

The research has also shown that these once villainized compounds are not nearly as dangerous as once believed. In fact, a 2020 German analysis ranking the risk of harm associated with various drugs ranked methamphetamine, heroin, alcohol, and cocaine as the most harmful drugs. At the opposite end of the graph, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and triptans were found to be the least likely to cause harm. Psychedelics and cannabis fell somewhere in the middle.70

A similar analysis out of the United Kingdom ranked various “recreational” substances in order of most to least harmful, including both risk to the user and risk to others.71 The authors ranked alcohol as the most harmful drug, with heroin and crack cocaine in second and third place, respectively. The least harmful drugs on the ranked scale were ecstasy, LSD, and mushrooms.72

Psilocybin (the active constituent in “magic mushrooms”) has been granted breakthrough therapy status twice by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) – first in 2018 for the treatment of treatment-resistant depression, and again in 2019 for the treatment of major depressive disorder.73 Cities around the country are voting to decriminalize the psychedelics, and in 2021 the state of Oregon not only decriminalized the possession of all “recreational” drugs in small quantities, but also legalized psilocybin-assisted therapy, being the first state in the USA to do so.74

The legalization of MDMA at the federal level is perhaps soon to follow.75 In January 2020, the FDA approved an expanded access program for MDMA-assisted psychotherapy, allowing 50 patients with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) to legally access treatment outside of Phase 3 clinical trials. The purpose of the Expanded Access program (which is also called “Compassionate Use”) is to allow people living with a serious or life-threatening condition to access potentially helpful investigational therapies.76 A similar program was approved in Israel in 2019.77

The secret is out: psychedelic substances are medicines.

The Psychedelic Dark Ages are behind us.

Dr. Erica Zelfand is a licensed family physician specializing in functional medicine and integrative mental health. In addition to supporting patients with their physical wellbeing, Erica facilitates psycho-spiritual experiences for individuals and groups across the globe. She regularly lectures on entheogenic science and trains aspiring psychedelic therapists in person and through her online CME-approved course, ScienceOfPsychedelics.com. When she isn’t trying to save the world, Erica can be found forest bathing, eating chocolate, and initiating group hugs (all of which, she would argue, may also help save the world). To learn more and connect, visit DrZelfand.com.