By Erica Zelfand, ND

The Psychedelic Renaissance is here, with powerful medicines like psilocybin, lysergic acid diethylamide-25 (LSD), and 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) back en vogue. But how did we get here? (Hold onto your seats, cosmonauts; we’re going on a trip.)

The Debut of Psychedelics in the West

The history of psychedelic medicines is perhaps as old as humanity, with evidence of the shamanic use of mushrooms dating as far back as 5000 BCE in Algeria. The soma drink mentioned in the Indian Rig Veda between 1500 and 1200 BCE was likely a brew of psilocybin-containing mushrooms and honey. Mushroom-shaped statues from 1500 BCE are evidence of the medicine’s sacred use in Central America.1-4

Psychedelic roots have also imbued elements of our modern-day practices, with the red-and-white color scheme of the Amanita muscaria mushroom reflected in Santa Claus’ suit. The early shamans of Siberia were thought to use the mushroom to engender mystical visions and “fly” in the realms of psychedelic insight. Rather than eating the mushrooms directly and risk being poisoned, however, the healers likely collected and drank the urine of reindeer that had consumed the mushroom – hence the Christmas trope of the flying reindeer.5,6

Despite the long, rich history of entheogenic use around the globe, however, the so-called developed world was rather late to the proverbial party. It was not until 1941 that the Harvard-trained ethnobotanist Richard Evans Schultes published his doctoral thesis on the identity of two hallucinogenic plants of Oaxaca, Mexico. His paper on the mushroom teonanácatl (Psilocybe mexicana) and the morning glory species ololiuqui (Turbina corymbosa) was groundbreaking yet largely ignored at the time, perhaps on account of the eruption of World War II in 1939.7

It would not be until at least 1957 that Americans would take an interest in psychedelic mushrooms, when Maria Sabina became the first Mexican modern-day curandera to serve los hongos (mushrooms) to a Westerner. Her client, the American amateur mycologist R. Gordon Wasson, husband of Dr. Valentina Pavlova Wasson, published a photo essay in Life magazine in 1957 describing his experience with the so-called “magic mushrooms” – and the rest, as they say, is history. It is rumored that the Beatles, Bob Dylan, and a host of other gringos (both famous and not) flocked to Sabina’s home village of Huatla de Jimenez, Oaxaca, to consume los hongos (this author being one such adventurer, though decades later than the celebrities).8-11

But back to the late 1930s, when Schultes’ papers were published and the world was rattled by the war, across the ocean, a Swiss chemist by the name of Albert Hofmann was working with various derivatives of ergot in hopes of developing a new cardiovascular drug. In the fall of 1938, Hofmann synthesized the twenty-fifth derivative of ergot, lysergic acid diethylamide-25 (LSD-25, or simply LSD). Initially dismissive of the derivative’s value, Hofmann forgot about it for five years. Inspired perhaps by intuition, Hoffman revisited the molecule in 1943, intentionally ingesting what he believed to be a miniscule amount of the substance. Hofmann then rode his bicycle home in the throes of what is now understood to be the world’s first-known “acid trip,” and which to this day is celebrated annually on April 19th as “Bicycle Day.”12

Although the psychedelic trip Hofmann experienced was more terrifying than glorious, it was clear he had stumbled upon a powerful compound. LSD-25 was branded “Delysid,” and Sandoz Laboratories began an international crowd-sourcing project to research commercial applications for the drug. Between 1949 and 1966, Sandoz Laboratories provided researchers (and clinicians willing to take notes) virtually unlimited quantities of the drug in exchange for their observations and insights.13-15

Between 1953 and 1973, the United States federal government too took interest in LSD-25. Four million dollars were spent funding 116 studies on the drug in research involving 1,700 subjects. Those numbers do not include the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA)’s classified research, done under the code name MK-Ultra. With the country engaged in the Vietnam War (November 1, 1955 – April 30, 1975), MK-Ultra focused on how LSD-25 could be used for mind control or otherwise weaponized. Some of the MK-Ultra studies were illegal; others downright unethical.16-18

One MK-Ultra research subject was Ken Kesey, who in 1960 was paid to take LSD-25 in a study. Kesey’s novel One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest was published two years later, in 1962. (The novel, Kesey explained, was less a book about mental illness than a story of how society pushes away those who do not conform.) In 1964, Kesey banded together with his friend Neal Cassady and their entourage of “Merry Pranksters” to introduce thousands of people to LSD-25 at “Acid Test” parties, which were often graced by the music of the Grateful Dead. Their Day-Glo painted Furthur bus is to this day an icon of the Hippie Generation.19-21

The psychologist Timothy Leary, PhD, was also among those experimenting with psychedelics. After reading Wasson’s Life article, the Harvard University professor traveled to Mexico in 1960 to try the psilocybin-containing mushrooms for himself. With the approval of the psychology department’s chair, Leary and his associate professor Richard Alpert, PhD, founded the Harvard Psilocybin Project. The two professors then administered psilocybin – and later LSD-25 – to hundreds of people in studies that often lacked a control group. Their research was criticized not only for its party-like atmosphere, but also for the researchers’ tendency to take drugs themselves alongside their subjects, some of whom were undergraduate students at Harvard. In 1963, both men were fired from Harvard University, but it was too late: the psychedelic movement had escaped the lab. Leary continued his work with psychedelics; Alpert went to India and returned as the spiritual teacher Ram Dass. In 1971 Ram Dass authored Be Here Now, a book on yoga, meditation, and spirituality that some have described as the Bible of the Hippie Generation.22-24

Unsurprisingly (at least in retrospect), turning thousands of young people on to powerful psycho-active substances did not always yield sunny outcomes. By the mid-1960s American emergency rooms were regularly visited by distressed and bewildered folks complaining of “bad trips” – a phenomenon that turned much of the medical community off of psychedelics altogether.

Nineteen sixty-seven (1967) marked the Summer of Love in the United States, with approximately 100,000 people converging in San Francisco. Two summers later, in 1969, the Woodstock Music Festival took place, at which half a million people gathered for “three days of peace and music” (plus sex and drugs). In November of that same year, growing opposition to the Vietnam War climaxed in the largest antiwar demonstration in United States history.25,26

The War on Drugs

Despite the US government’s initial enthusiasm for researching psychedelic compounds, the merits of the drugs were ultimately dismissed with the Nixon administration’s Controlled Substances Act of 1970. It has been suggested that Nixon’s anti-drug stance had less to do with a legitimate concern for public safety than with a disdain for certain demographics – namely Blacks and anti-war hippies.27>

John Daniel Ehrlichman, counsel and assistant to the President for domestic affairs during the Nixon years, once summarized it like this:

The Nixon White House… had two enemies: the antiwar left and black people. You understand what I’m saying? We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or blacks, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.28

Nixon – who was himself no stranger to alcohol or prescription drugs – once described Leary as “the most dangerous man in America.”29,30

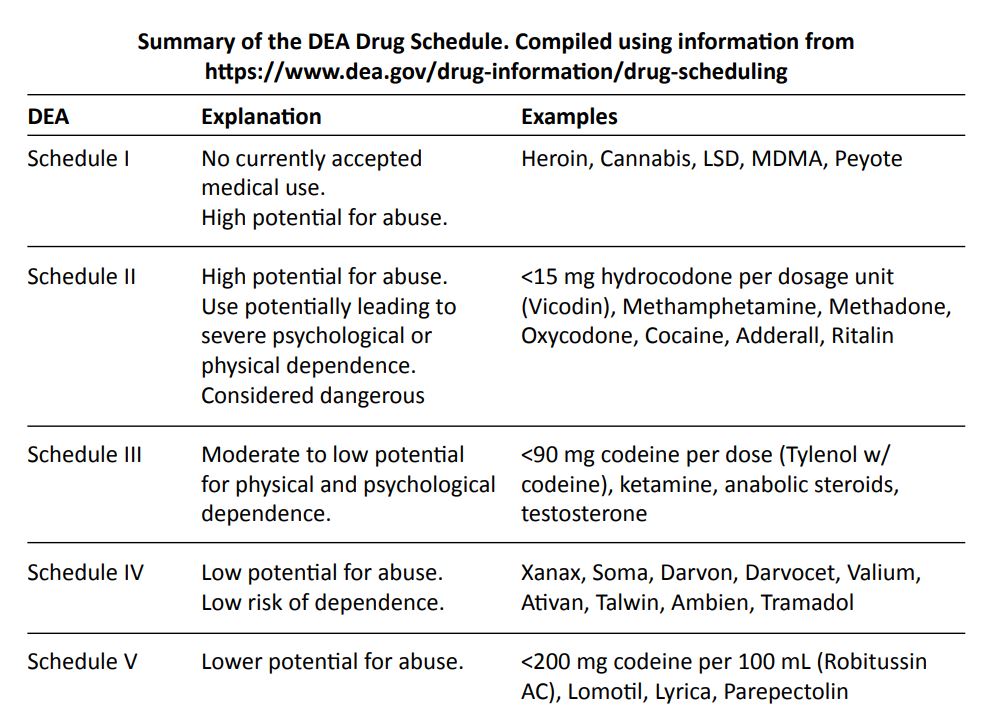

The 1970 Controlled Substances Act created five schedules used to classify drugs based on their abuse potential, accepted medical use in the USA, safety, and potential for addiction.13 Drugs placed in Schedule I became illegal overnight, categorized as having a high potential for abuse and no accepted medical use. Medicines categorized as Schedule I drugs to this day include LSD-25, cannabis, and heroin.32

The term “War on Drugs” was popularized by the media after a press conference on June 18, 1971, in which Nixon referred to drug abuse as “public enemy number one.” In 1973, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) was created.33,34

During the presidency of Ronald Reagan (1980 – 1988) MDMA, the active constituent of the street drugs “Molly” and “Ecstasy,” was added to Schedule I, despite the fact that the drug had shown promise as a powerful adjuvant to psychotherapy.35

Article continues on next page…