by Sandro D’Amico, ND

A dichotomy in the conception of mind and body has long existed in Western thought and continues to permeate the organization and practice of medicine. For example, many who practice alternative medicine have heard stories from patients about encounters with physicians who told them their somatic symptoms were “psychological” because nothing had been found on lab tests, or the patient’s symptoms did not conform to an accepted diagnosis. Paradoxically, conditions classically seen as psychological, such as depression and anxiety, are now viewed and treated almost exclusively as neurochemical disorders, while stress and trauma histories are largely ignored. It seems to me that the phenomenon of “biography” becoming “biology” is an awkward subject in medicine. There are many reasons for this, including personal, professional, and cultural biases; economic pressures; a lack of awareness of research on the subject; and a lack of awareness of effective therapies for patients suffering from the effects of adverse life experiences. All of this occurs, of course, within a larger societal context in which the impact of traumatic experiences on affect, behavior, and physical health are routinely minimized.

Nonetheless, physicians see patients in their practices daily who have histories of child abuse or neglect, spousal abuse, sexual or physical assault, loss of loved ones, serious automobile accidents and other injuries, active combat experience, and other potentially traumatic experiences. Given this, it may be clinically useful to consider the impact of such experiences on both physiology and pathology and to examine how this knowledge might be used to help our patients heal.

Defining Trauma

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is the most widely recognized trauma-related disorder and, as such, serves as a good model for understanding the underlying processes involved in psychoemotional trauma in general. Symptoms include distressing, intrusive memories of the event; flashbacks in which the individual feels or responds as if the traumatic event were actually occurring again; marked psychological and physiological reactions to internal and external cues that resemble an aspect of the trauma; and negative alterations in cognition and mood.1

The symptoms experienced in PTSD result from the chronic upregulation of innate survival responses within the central nervous system. Neurologically, the evaluation of potential threat is an ongoing and, for the most part, unconscious process involving communication among a number of cortical and subcortical structures. With the exception of olfaction, which projects directly to the amygdala, all sensory information entering the CNS is initially routed simultaneously to the locus coeruleus and the thalamus in the brainstem. These structures share extensive interconnectivity with the amygdala and hippocampus, as well as the orbitofrontal and medial prefrontal cortices.2 The locus coeruleus is a key structure in threat assessment and response, and has extensive noradrenergic projections to the amygdala, hippocampus, and cerebral cortex.3 The amygdala and hippocampus are involved in memory formation and assigning emotional relevance to both memory and novel stimuli.4 The orbitofrontal and medial prefrontal cortices are involved in higher-level assessment of potential threat and mediate either further activation or downregulation of the arousal response.5

When a possible threat is perceived as being relevant, defensive responses are activated. These include social engagement (seeking help), fight, flight, and freezing. Mobilization of these responses occurs via the sympathetic nervous system, somatic nervous system, and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. In the case of freezing, simultaneous activation of sympathetic and parasympathetic resources occurs. In a healthy nervous system, when a threat is successfully negotiated and safety reestablished, defensive responses are downregulated and physiology returns to homeostatic baseline. The central physiopathology of posttraumatic states is a failure of the capacity to downregulate defensive responses.6,7

PTSD and other posttraumatic states occur when the level of threat is perceived as being extreme and successful enactment of defensive responses fails. In other words, trauma tends to occur when a perception of severe threat is combined with a simultaneous perception of powerlessness to self protect. This untenable situation leads to neurological changes involving heightened engagement of survival mechanisms, and downregulation of the modulating functions of the neocortex.8 Studies have shown reduced volume of the orbitofrontal and medial prefrontal cortices in individuals with PTSD, as well as decreased blood flow to the medial prefrontal cortex in veterans with PTSD exposed to non-trauma-related stressful stimuli.9-11 In addition, decreased functional connectivity between the medial prefrontal cortex and amygdala, and increased amygdala activation on exposure to fearful stimuli has been documented.12

Posttraumatic neurophysiological states persist largely due to the ongoing influence of trauma-associated memory on nervous, endocrine, and musculoskeletal function. Memories formed during extreme stress are laid down along alternate neurological pathways and are more procedural in nature. Procedural memory is a largely unconscious form of memory involved in the development of conditioned sensorimotor responses. Narrative elements of traumatic memory are often fragmented, while the procedural elements directly and powerfully influence physiology and behavior. Chronic reactivation of procedural memory causes persistent disruption of homeostasis to the CNS, autonomic nervous system, somatic nervous system, endocrine system, and the organs and tissues that they regulate.13,14 It should be noted that while much of our understanding of trauma comes from research into PTSD, many of the same underlying neurophysiological disruptions occur in traumatized individuals who do not meet the criteria for PTSD.15,16

Prevalence

Lifetime prevalence of PTSD in American adults has been estimated at about 7%, although rates in specific types of traumatic exposure vary considerably.17 Studies of US veterans returning home from active duty in Iraq have reported rates between 4% and 17%.18 Approximately 9% of individuals involved in a motor vehicle accident subsequently develop PTSD.19 A large study of female sexual assault survivors found PTSD rates of 35.3% in those assaulted for the first time before age 18 and 30.2% for those first assaulted after age 18.20

In the course of their life, virtually every human being will experience at least a few events that put them at risk for traumatic stress. Roughly 2.5 million Americans have served in Iraq or Afghanistan, many of them on multiple deployments.21 Every year about 1 in 100 US residents is injured in a motor vehicle accident.22 The US Department of Justice reports that, in 2014 alone, there were over 4,400,000 violent assaults, over 660,000 robberies, and over 280,000 reported incidences of rape in the US.23 It should be kept in mind that sexual assaults are grossly underreported, with the Bureau of Justice estimating that only 36% of rapes are reported to law enforcement.24

with childhood abuse or PTSD compared to non-traumatized controls.

Children, who are both neurologically and circumstantially the most vulnerable, also have a high incidence of exposure to traumatic stressors. The Department of Health and Human Services estimates that 10.5% of children live with at least one parent who has an alcohol use disorder.25 In a recent survey of 4503 children published in JAMA Pediatrics, 41.2% of children reported a physical assault within the last year and 10% reported an assault-related injury.26 19.3% of respondents in Felitti et al.’s Adverse Childhood Experiences study (ACE) reported having been touched or fondled in a sexual way by an adult or other older person. 8.9% reported attempted oral, vaginal, or anal intercourse, and 6.9% reported actual oral, vaginal, or anal intercourse by an older person.27

Trauma in the Clinic

ACE was a landmark study for several reasons. It was a large study with over 8000 participants that not only confirmed previous research on the prevalence of child maltreatment but also found compelling associations between the extent of adverse childhood experiences, later participation in known disease risk factors, and the actual occurrence of disease in adulthood. ACE looked at seven areas of potentially traumatic exposure before age 18: psychological, physical, or sexual abuse; witnessing violence against the mother; or living with household members who were substance abusers, mentally ill, suicidal, or ex-convicts. The study found a dose-response relationship between the number of childhood exposures and the number of disease risk factors in adult participants, including smoking, severe obesity, physical inactivity, depression, alcoholism, illicit drug use, high number of sexual partners, and history of suicide attempt.28

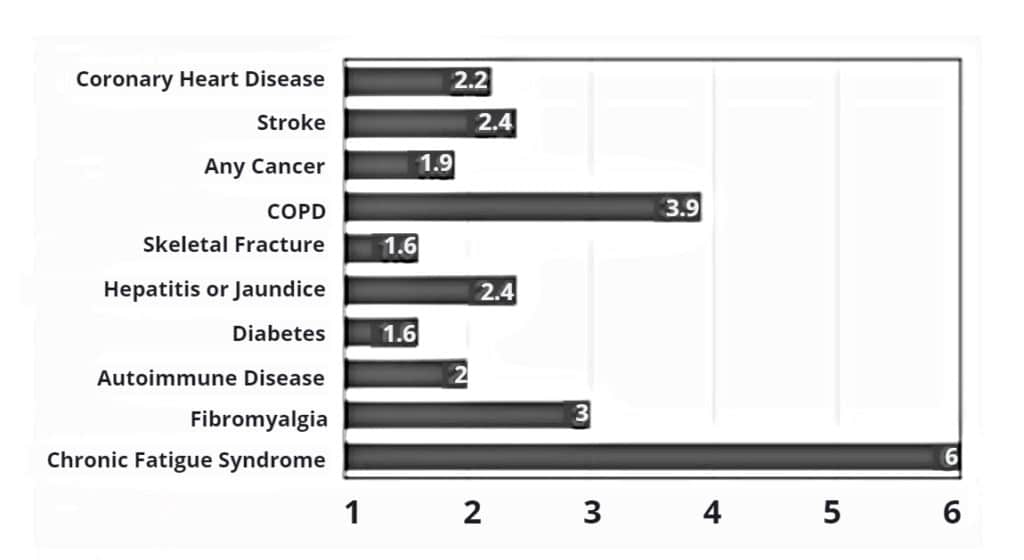

In addition, the study found striking correlations between the number of childhood exposures and the very disease conditions that are responsible for the bulk of morbidity and mortality in developed nations: ischemic heart disease, cancer, chronic bronchitis and emphysema, history of hepatitis or jaundice, skeletal fractures, and poor self-rated health. Dose-response relationships were also found for diabetes and stroke but did not achieve statistical significance. Compared with participants who reported no exposures, participants reporting four or more exposures had the following ratios of increased risk: ischemic heart disease: 2.2, any cancer: 1.9, chronic bronchitis or emphysema: 3.9, skeletal fracture: 1.6, hepatitis or jaundice: 2.4, diabetes: 1.6, and stroke: 2.4.29

The increased rates of disease reported in the ACE study can be attributed, at least in part, to the increased risk-associated behaviors found in participants with abuse histories. There is a growing body of evi-dence, however, that the physiological dysregulation brought on by trauma is, in and of itself, predisposing toward a number of chronic diseases. Perhaps not surprisingly, these conditions tend to involve the immune, endocrine, nervous, and digestive systems.

One significant health impact of chronic traumatic stress appears to be upregulation of inflammatory mediators. A number of studies have found increased levels of C-reactive protein, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor alpha in individuals with PTSD.30,31 Elevated levels of these cytokines is associated with a wide variety of disease conditions, including cardiovascular disease, peripheral vascular disease, stroke, many cancers, many autoimmune diseases, and depression. While the ACE study demonstrated an association with cardiovascular disease, stroke, and cancer, it did not examine rates of autoimmune diseases. A recent study of over 600,000 Iraq and Afghanistan veterans looked at rates of thyroiditis, inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, and lupus in veterans with PTSD or another psychiatric diagnosis, compared with those with no psychiatric diagnosis. Veterans with a psychiatric diagnosis other than PTSD had a relative risk of 1.51 for one or more of the autoimmune conditions studied. Those with PTSD had a relative risk of 2.0. As might be expected, rates of autoimmune conditions were considerably higher in women than in men. The prevalence of any autoimmune condition in male veterans was 0.9% for those without a psychiatric diagnosis, 1.2% for those with a psychiatric diagnosis other than PTSD, and 1.7% for those with PTSD. For female veterans the prevalence was 2.5%, 3.1%, and 5.4% respectively.32

A number of other disease conditions are also associated with a history of psychological trauma. Increased levels of chronic pain have been reported in individuals with a history of childhood abuse.33 In addition, several studies have found higher rates of fibromyalgia in individuals with PTSD. While study design and results have varied somewhat, in general, fibromyalgia has been found to be at least 3 times more prevalent in those with PTSD than those without.34,35 In one study of 395 fibromyalgia patients, 45.3% met the criteria for PTSD, as compared with 3% of population controls.36 Perhaps not surprisingly, chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) is also more common in those with PTSD or a history of abuse. One recent study found that individuals with PTSD were 8 times more likely to have a history of CFS.37 Another study found that exposure to childhood trauma incurred a 6-fold increased risk of developing CFS. The researchers went so far as to conclude, “Neuroendocrine dysfunction, a hallmark feature of CFS, appears to be associated with childhood trauma. This possibly reflects a biological correlate of vulnerability due to early developmental insults.”38 Other conditions in which an association to psychological trauma has been found include irritable bowel syndrome, premenstrual syndrome, anorexia and bulimia nervosa, substance abuse disorders, depression, and anxiety.39-43

Identifying Trauma in Patients

In my experience, identifying a history of psychological trauma or PTSD in patients is not difficult. Patients often volunteer information about their trauma history if they believe that it is related to their condition. Indeed, many have been trying to get doctors to take their trauma history seriously for years. Others will not volunteer but will answer honestly when asked. I have encountered relatively few patients with strong evidence of autonomic dysregulation who deny having a trauma history. Often a simple question such as, have you had any major stresses or traumatic experiences in your adult life? What about your childhood? is sufficient to start a conversation. In addition, standardized questionnaires, such as the PTSD Checklist can be used.44 There are no laboratory measures that are exclusively associated with posttraumatic stress; however, diurnal cortisol rhythm and heart rate variability studies will often be abnormal.45-47 In my opinion, assessing the possibility of posttraumatic stress is warranted in any patient with strong evidence of autonomic dysregulation, or with any condition or risk-associated behaviors that have a strong correlation with psychological trauma.

Healing Trauma

The dominant psychotherapeutic approaches in use today for PTSD are cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR). CBT is the most common form of “talk therapy” in use by psychotherapists, and while it is generally considered effective, research has shown nonresponse rates of up to 50% in recipients with PTSD. Poor response has been associated with deficits in verbal memory, anxiety, and greater amygdala and ventral anterior cingulate activation.48 All of these are quite common in patients with PTSD.

EMDR involves holding a traumatic memory in mind while the therapist provides some form of bilateral sensory stimulation, originally the movement of a finger back and forth in front of the client’s eyes. The client then follows the train of images, thoughts, and emotions that emerge as the therapist continues to apply bilateral stimulation. Although here have been anecdotal reports of rapid improvement of PTSD symptoms in some patients, comparative research has consistently shown EMDR to be no more effective than CBT in the treatment of PTSD.49,50 Bessel van der Kolk, a prominent PTSD researcher and clinician, asserts that EMDR works well for specific, emotionally charged memories, but not for complex forms of childhood maltreatment.51 This may explain the discrepancy between anecdotal reports and research outcomes.

While CBT and EMDR are certainly helpful, it is unclear to what degree they actually alter the physiological dysregulation underlying trauma, a key question from a medical standpoint. The majority of studies examining CBT and EMDR have used psychological measures, such as scores on PTSD rating scales and quality-of-life questionnaires as their endpoints. Having seen many patients who had undergone psychotherapy prior to seeing me, my personal impression is that psychotherapy, as it is generally practiced, results in only modest improvements in physiological self-regulation. For those who do not respond well to conventional psychotherapy, there are, thankfully, a number of alternative therapies that show promise.

Several somatically based therapies have been developed for the treatment of psychoemotional trauma. These include Somatic Experiencing, Sensorimotor Psychotherapy and Self Regulation Therapy. These therapies currently lack validation by clinical trials; however, unlike CBT and EMDR, they are modeled more directly on current scientific understanding of the neurophysiology of trauma. The common goal of these therapies is to assist patients in completing thwarted defensive responses which appear to remain encoded cortically and subcortically as part of the patient’s trauma associated procedural memory.52 Because CNS-autonomic arousal is perceptible as sensations in the body, these therapies use mindful awareness of somatic sensations as a guide to identifying and completing neurological and motor defensive responses.53,54 I use Self Regulation Therapy in my practice and find that it often has a dramatic effect on hyperarousal symptoms such as emotional reactivity to stress, startle response, and sleep disturbances.

Several forms of biofeedback have been used in PTSD. Neurofeedback, also known as EEG biofeedback, uses computer-generated real-time feedback of brain activity to teach self regulation. Several studies have shown positive effects in PTSD, including improved cortical and subcortical connectivity and substantial improvements in PTSD symptoms over time.55-57 Studies have also shown improvements in a number of somatic conditions strongly associated with autonomic dysregulation and traumatic stress, including insomnia, fibromyalgia, and migraine headaches.58-60 Heart rate variability biofeedback has also been shown to improve self-regulation in veterans with PTSD.61

The use of meditation for the treatment of posttraumatic stress has been fairly well studied. A number of types of meditation have been examined, including Sudarshan Kriya Yoga, loving-kindness meditation, mindfulness meditation, and Transcendental Meditation (TM).62,63 All forms of meditation studied have shown positive results. Perhaps the most striking results to date were demonstrated in a two-arm study of TM involving 73 Congolese refugees with PTSD. Scores on the PTSD Checklist (PCL-C) were reduced by over 50% at 30 days in those practicing TM and remained low for the remainder of the study, while scores for those not meditating actually increased slightly.64 Another study of TM showed increased activity in the medial prefrontal cortex, while a study of mindfulness meditation showed decreased activity in the amygdala of adults exposed to stress.65,66 Both of these neuroplastic changes are consistent with improved self-regulation.

Conclusion

Self-regulation is one of the fundamental functions of the central nervous system and is essential for long-term health. Psychoemotional trauma is a common source of chronic dysregulation and plays a significant role in the morbidity seen daily in most medical offices, not to mention its profound contribution to psychological suffering. While the concept of self-regulation and its association to trauma may be new to some alternative physicians, most are already treating dysregulation via such therapies as balancing neurotransmitters, hormones, and the HPA axis. For patients with significant trauma, however, standard alternative therapies may not be enough. Providing or referring patients for therapies that address the physiopathology of trauma more directly may have a substantial impact on their recovery. Furthermore, some therapies that help to restore neurological self-regulation, such as neurofeedback, heart rate variability biofeedback, and meditation training, can be fairly easily integrated into many alternative medical practices. Lastly, for many patients, the simple matter of having a doctor who actually understands what they’ve been through and how it is affecting them will have a healing power in itself.

Sandro D’Amico holds a BA in psychology from the Union Institute & University, where his studies emphasized the influence of psychological factors on health and illness. He received his doctor of naturopathic medicine degree from Southwest College of Naturopathic Medicine in 2002, where he also completed his residency. Dr. D’Amico’s long-held fascination with psychophysiology led him to specialize in the treatment of mental health conditions using alternative therapies. In addition to his standard naturopathic training, his postgraduate studies have included 2 years of study at the Canadian Foundation for Trauma Research and Education and extensive study and research into the use of nutritional therapies in mental health. He currently lives and practices with his wife, Dr. Greta D’Amico, in Auburn, California.