By Erik Peper, PhD, Richard Harvey, PhD,

Yanneth Cuellar, and Catalina Membrila

San Francisco State University

This article is reprinted from NeuroRegulation: Peper E, Harvey R, Cuellar Y, Membrila C. (2022). Reduce anxiety. NeuroRegulation, 9(2), 91–97. https://doi.org/10.15540/nr.9.2.91 https://www.neuroregulation.org/article/view/22815/14575

Abstract

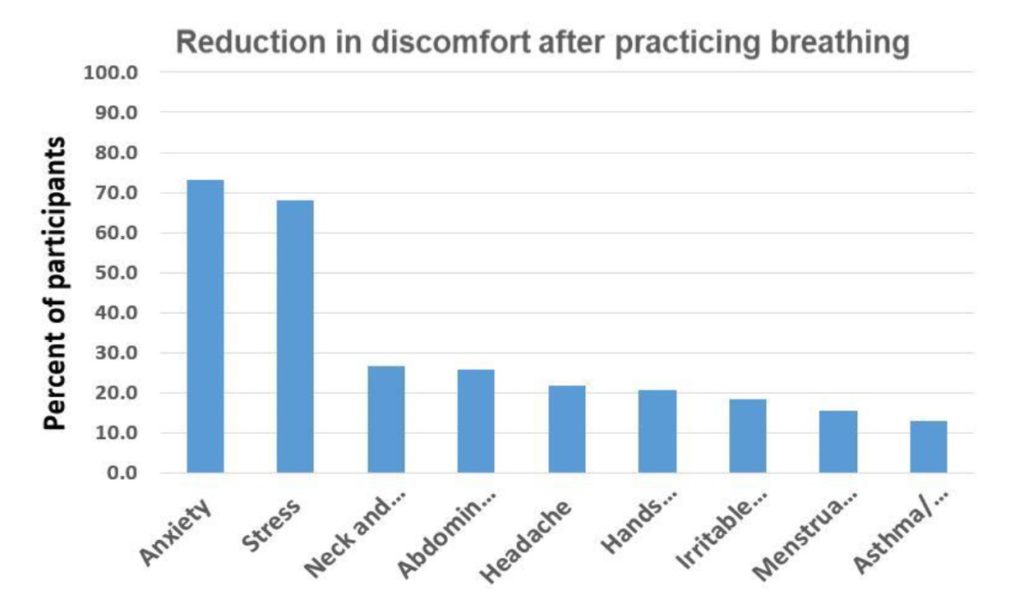

More than half of college students self-report some kind of anxiety and depression. This study reports how a university course that incorporated structured self-experience practices may reduce symptoms of self-reported anxiety associated with college stress and strain. 98 college Junior and Senior students were enrolled in a Holistic Health class that focused on ‘whole-person’ Holistic Health curriculum and included the exploration of psychobiology of stress, the role of posture, and the psychophysiology of respiration. The class included daily self-practices of awareness of stress, muscle relaxation, diaphragmatic breathing and posture awareness. The students were instructed to apply these techniques whenever they become aware of, or experienced, sensations of stress or dysfunctional breathing during the day. After five weeks of practice, the students self-reported a 73% reduction in anxiety, 68% reduction in stress, 27% reduction in neck and shoulder discomfort, 26% reduction in abdominal discomfort; 18% of abdominal discomfort and 16% reduction in menstrual cramps. We recommend that schools incorporated a ‘whole-persons’ self-care approach within their curriculum to teach students skills to prevent and reduce anxiety and stress and therapists teach these skills before beginning bio/neurofeedback.

As a result of my practice, I felt my anxiety decrease as well as it reduced my menstrual cramps. I felt very calm and felt my anxiety at ease especially on the days where my anxiety was eating me alive. –College senior

When I changed back to slower diaphragmatic breathing I was more aware of the negative emotions and I was able to reduce the stress and anxiety I was feeling with the deep diaphragmatic breath. -College junior

More than half of college students now self-report some kind of anxiety (Coakley et al., 2021). Before the COVID-19 pandemic nearly one-third of students had or developed moderate or severe anxiety or depression while being at college (Adams et al., 2021). The pandemic accelerated a trend of increasing anxiety that was already occurring. “The prevalence of major depressive disorder among graduate and professional students is two times higher in 2020 compared to 2019 and the prevalence of generalized anxiety disorder is 1.5 times higher than in 2019” as reported by Chirikov et al (2020) from the UC Berkeley SERU Consortium Reports.

In an anonymous survey during the first day of a spring semester class, 59% of the students reported feeling tired, dreading their day, being distracted, lacking mental clarity and had difficulty concentrating. Unsurprisingly, these are some of the same symptoms corresponding with the prevalence of anxiety and depression, other types of stress, and strain observed in college students as reported by Beiter et al. (2015).

The increases in symptoms of stress and strain, such as in anxiety, has both short- and long-term performance and health consequences. Severe anxiety reduces cognitive functioning and is a risk factor for early dementia many years after students leave college (Bierman et al., 2005; Richmond-Rakerd et al, 2022). Chronic severe anxiety also increases the risk of many kinds of co-morbid health issues, listed here alphabetically, such as asthma, arthritis, back/neck problems, chronic headaches, diabetes, heart disease, hypertension, pain, obesity, and ulcers (Bhattacharya et al., 2014; Kang et al, 2017).

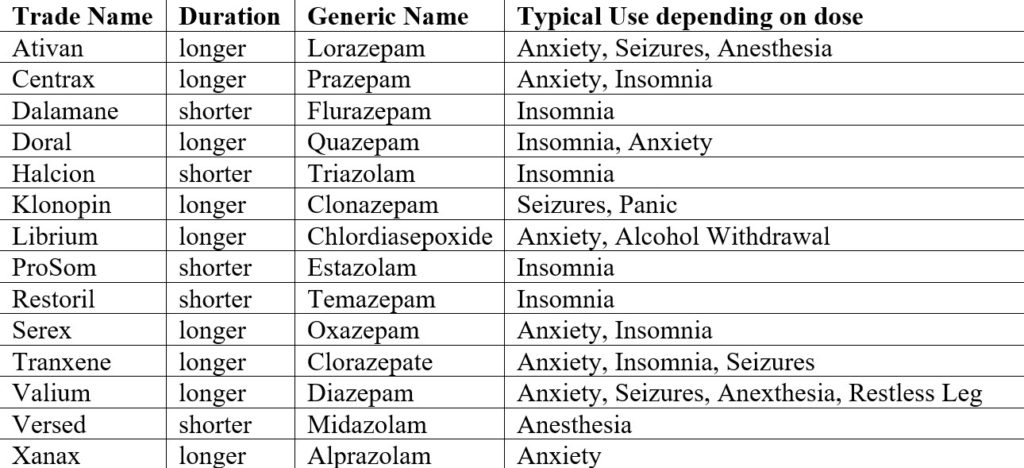

The most used medical treatment approaches for anxiety are various pharmaceutical drugs (Kaczkurkin & Foa, 2015). These anti-anxiety drugs are sedative medications (e.g. benzodiazepines; Bushnell et al., 2017). Unfortunately, side effects of sedating medications like benzodiazepines include drowsiness, irritability, dizziness, memory and attention problems, and physical dependence (Crane, 2013; Peppin et al., 2020; Shader & Greenblatt, 1993; Shri, 2012). Note that the most typical uses for sedating medications (arranged alphabetically by trade name) are for issues relating to anxiety and insomnia (Table 1).

Sedating medications (benzodiazepines) are restricted under the Controlled Substances Act under Schedule IV. The most common prescription medications for anxiety are trade named Valium, Xanax, Halcion (short acting), Ativan and Klonopin. Benzodiazepines may have toxic or fatal interactions when combined with alcohol, barbiturates, and other non-benzodiazepine/non-barbiturate sleeping pills such as Zolpidem (Ambien), Eszopicione (Lunesta), Zopicione (Somnol) and Zaleplon (Sonata).

Because benzodiazepine medications work by enhancing the effects of a neurotransmitter that slows down nervous system excitability and regulation of muscle tone (e.g. Gamma-Amino Butyric Acid or GABA; Toosi et al., 2017), it is plausible that many behavioral techniques that influence anxiety may also influence regulation of neurotransmitters that slow down regulation of muscle tone and nervous system excitability (Bandelow et al., 2015).

The most commonly used non-medical treatment approaches for anxiety are Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) techniques based upon the assumption that anxiety is primarily a disorder in thinking which then influence the symptoms and behaviors associated with anxiety (Marker, et al., 2018; Smits, et al., 2008). In an oversimplification, the primary treatment intervention by CBT practitioners focuses on changing thoughts which co-occur with behaviors and physical measures of psychophysiology .

Prior research (cf. Peper, Harvey & Hamiel, 2019) suggests transforming ‘hopeless, helpless, depressive’ thoughts into ‘empowering’ thoughts, has enhanced efficacy when a person first shifts to an upright posture, and then begins slow diaphragmatic breathing, before finally reframing their hopeless/helpless/negative thoughts into empowering/positive thoughts. Participants were able to reframe stressful memories much more easily when in an upright posture compared to a slouched posture. Those who incorporated posture-plus-reframing reported a relevant reduction in negative thoughts and self-reported anxiety compared to those with no posture change while attempting to reframe their thoughts. Whereas the relationship between postural changes (e.g. ‘power poses’) and hormones associated with dominance or submission (e.g. testosterone levels) is still under investigation (Korner et al., 2020; Metzler et al., 2019), it has been proposed that ‘power poses’, such as those poses practiced in various Yoga traditions, may act on the body by enhancing the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA (Streeter, et al., 2018). As suggested by Peper, Harvey and Lin (2019b) as well as Streeter, et al., (2020), behavioral strategies that enhance attention, influence posture, as well as regulate breathing, all have a positive effect on emotions and behaviors.

Simplifying a complex relationship between mechanisms involving GABA, testosterone and anxiety behaviors can be difficult; however regulation of GABA has been associated with lowered anxiety in humans and animals (e.g. Lowery-Gionta, et al., 2018; Smith, et al., 2017; Thayer, 2006). There are strategies to reduce anxiety that focus on breathing and posture change. At the same time, there are many other factors that may contribute to the onset or maintenance of anxiety such as social isolation, economic insecurity, etc. In addition, low glucose levels can increase irritability and may lower the threshold of experiencing anxiety or impulsive behavior (Barr, Peper, & Swatzyna, 2019; Brad et al, 2014). This is often labeled as being “hangry” (MacCormack & Lindquist, 2019). Thus, changing a high glycemic diet to a low glycemic diet may reduce the somatic discomfort (which can be interpreted as anxiety) triggered by low glucose levels. In addition, people are also sitting more and more in front of screens. In this position, they tend to breathe quicker and more shallowly in their chest.

Shallow, rapid breathing tends to reduce the partial pressure of carbon dioxide (pCO2) which has normal values between 35 to 45 mmHg. Reduced pCO2 contributes to subclinical hyperventilation which could be interpreted as a symptom of anxiety (Lum, 1981; Wilhelm et al., 2001; Du Pasquier et al, 2020). Experimentally, the body sensations that co-occur with experiences of anxiety can be evoked by instructing a person to sequentially exhale about 70% of their inhaled air, continuously for 30 seconds. After 30 seconds, participants report a significant increase in self-reported anxiety (Peper & MacHose, 1993). During the period of the COVID-19 pandemic when college students spent many hours sitting in front of a computer screen with ‘shallow breathing’ and having hopeless, helpless thoughts from the pandemic may all be cofactors that contribute to the self-reported increases in anxiety symptoms.

To reduce symptoms related to anxiety and discomfort in college students, McGrady and Moss (2013) suggested that self-regulation and stress management approaches could be offered as the initial treatment/teaching strategy in health care instead of first offering medication. Another useful approach to reduce sympathetic arousal and optimize health in college students is breathing awareness and retraining as described by Gilbert (2003).

The purpose of this report is to describe how a university course curriculum that incorporated structured self-experience practices may reduce symptoms of self-reported anxiety associated with college stress and strain (Peper, Miceli, & Harvey, 2016). For several decades starting in 1976, up to 180 undergraduates have enrolled in a three-unit Holistic Health class on stress management and self-healing (Klein & Peper, 2013). Students in the class are assigned self-healing projects using techniques that focus on awareness of stress, ‘dynamic regeneration,’ stress reduction imagery for healing, and other behavioral change techniques adapted from the book, Make Health Happen (Peper, Gibney & Holt, 2002). At the end of the semester, 4 out of 5 of students (82%) self-reported that they were ‘mostly successful’ in achieving their self-healing goals. Students have consistently reported achieving positive benefits such as increasing physical fitness; improving diets; and reducing symptoms of anxiety, depression, and pain; eliminating eczema; and, even reducing substance abuse (Peper et al., 2003; Bier et al., 2005; Peper et al., 2014). This survey explores the change in self-reported anxiety, stress and other somatic symptoms after practicing ‘whole-person’ Holistic Health stress management program that included the exploration of psychobiology of stress, the role of posture, psychophysiology of respiration, and daily self-practices.

Method

Participants: 98 college junior and senior students enrolled in a holistic health class for the experimental group. At the same time 12 students in another class served as controls. As a report about an effort to improve the quality of a classroom activity, this report of findings was exempted from Institutional Review Board oversight.

Procedure: Students were enrolled in a Holistic Health class that focused on the psychobiology of stress, the role of posture, and the psychophysiology of respiration. For five weeks, the class included didactic presentations along with guidance for daily self-practice in paced-breathing and posture awareness while sitting or using a computer.

Didactic lecture content. Didactic class presentations on the psychophysiology of stress, how mind emotions impact body, how body affect mind and emotions, and how posture impacts health (Sapolsky, 2004). It included discussions about the physiology of breathing and how a constricted waist tends to cause the person to breathe more in their chest (the cause of neurasthemia) and how the fight/flight response may trigger chest breathing, breath holding and/or shallow breathing.

The lectures include short experiential practices of the body-mind connections such as imagining a lemon to increase salivation, the effect of slouched versus erect posture on evoking positive/empowering or hopeless/helpless/powerless/defeated thoughts, and the effect of sequential 70% exhalation for 30 seconds on increasing anxiety (Peper, Gibney, & Holt, 2002; Tsai, Peper, & Lin, 2016; Peper, Lin, Harvey, & Perez, 2017; Peper & MacHose, 1993).

Daily self-practice. Students were assigned daily self-practices focusing on skill mastery (e.g gradually building to 20 minutes of practices daily) and implementing the skills during their daily life. Students recorded their experiences after their practice. At the end of the week, they reviewed their own log and summarized their observations (benefits, difficulties), then met in small groups to discuss their experiences and extract common themes. These daily practices included the following:

- Awareness of stress by monitoring their reactions to daily stressors.

- Practicing dynamic relaxation for 20 minutes a day and then observe and inhibit bracing pattern during the day.

- Changing ‘energy drain and energy gains.’ Students observed what events reduced or increased their subjective energy and were instructed to implemented changes in their behavior to decrease events that reduced their energy and increased behaviors that increase their energy.

- Creating a ‘memory of wholeness’ which consisted of evoking a past memory when they felt healthy and well. They would relax and then recall and evoke this memory.

- Practicing effortless breathing. Students practiced slow diaphragmatic abdominal breathing at approximately 6 breaths-per-minute pace, for 10-20 minutes per day. Even more importantly, each time they become aware during the day of dysfunctional breathing pattern (e.g., breath-holding, shallow chest breathing or, gasping), they would change to an erect power posture and shift to slower diaphragmatic breathing.

After five weeks students filled out an anonymous survey in which they rated the change in anxiety and other symptoms as compared to the beginning of the semester. The control group filled out the same questionnaire.

integrated stress management and diaphragmatic breathing

Result. It will come as no surprise that the majority of students reported improvement. 73% reported a reduction in anxiety and 68% reported a reduction in stress. In addition, they reported decreases in their symptoms of stress, neck and shoulder, abdominal discomfort, headaches, irritable bowel/acid reflux, menstrual cramps as shown in Figure 1.

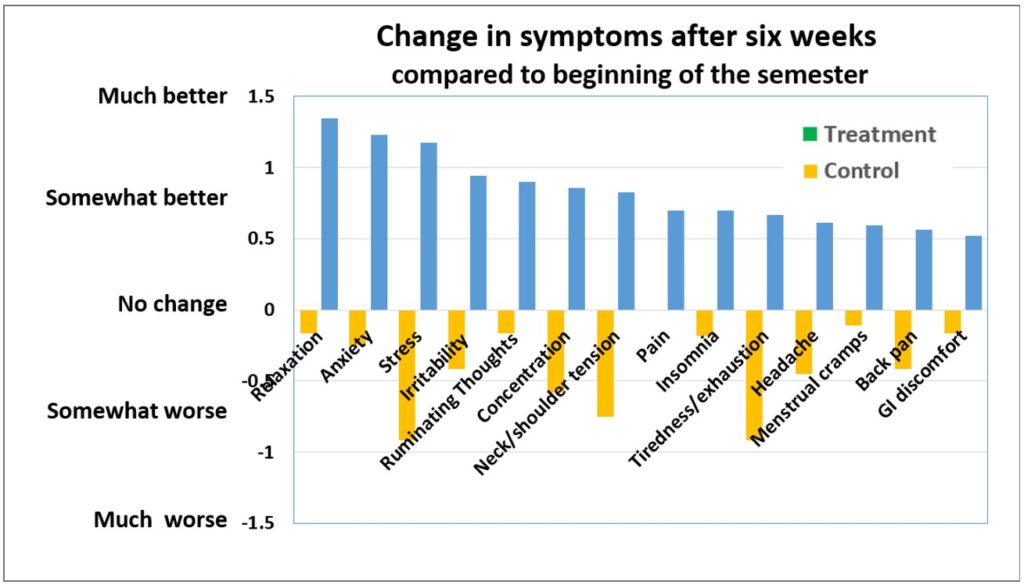

The control group did not report a decrease in symptoms instead they reported a slight increase in anxiety, stress and somatic symptoms as shown in Figure 2. In addition, although not assessed on the symptom questionnaire, most students anecdotally reported an increase in mental clarity and concentration that improved their study habits. As one student noted:“Now that I breathe properly, I have less mental fog and feel less overwhelmed and more relaxed. My shoulders don’t feel tense, and my muscles are not as achy at the end of the day.”

to the beginning of the semester for the treatment and control group.

Discussion

Almost all students were surprised how beneficial these easily learned practices were to reduce their symptoms of anxiety along with other symptoms of depression, stresses and strains while other students not in this class informally reported an increase in anxiety and somatic symptoms. Arguably the most important skill students learned was to interrupt their individual stress responses throughout the day, including shifting to diaphragmatic breathing. The more they practiced during the day, the more benefits they reported in reducing their symptoms. In summary, the major factors that contributed to the students’ improvement were:

- Learning through self-mastery as an education approach versus clinical treatment.

- Generalizing the skill into daily life and activities. Practicing the skill during the day in which, the cue of a stress reaction triggered the person to shift to an upright position and breathe slowly which would reduce their sympathetic activation.

- Interrupting escalating sympathetic arousal. Responding with an intervention reduced the sense of being overwhelmed and unable to cope by the participant performing an active task.

- Redirecting attention and thoughts away from the anxiety trigger to a positive task of diaphragmatic breathing.

- Increasing heart rate variability through slower breathing which enhanced sympathetic parasympathetic balance.

- Reducing subclinical hyperventilation by breathing slower and thereby increasing pC02.

- Increasing social support by meeting in small groups. The class discussion group normalized the anxiety experiences.

- Providing hope. The class lectures and assigned readings and videos provide hope since students read case reports and watched videos of other students who had had reversed their chronic disorders such as irritable bowel disease, acid reflux, psoriasis with behavioral interventions.

Although the study lacked a systematic control group and is only based upon self-report (e.g. correlated), this approach represents an economical non-pharmaceutical approach to reduce anxiety. The stress management strategies referred to may not resolve anxiety for everyone. By practicing and implementing these skills the moment the student comes aware of, or experiences symptoms of stress (sloughing shallow breathing or breath holding, neck and shoulder tension, etc.), they reduce the development of symptoms and enhance health. Nevertheless, we recommend that schools implement this non-pharmacological educational approach into the classroom to reduce anxiety and stress related disorders and therapists teach this approach first before beginning bio/neurofeedback.

To quote another student “I noticed that breathing helped tremendously with my anxiety. I was able to feel okay without having that dreadful feeling stay in my chest and I felt it escape in my exhales. I also felt that I was able to breathe deeper and relax better altogether. It was therapeutic, I felt more present, aware, and energized.”

Author Disclosure

Authors have no grants, financial interests, or conflicts to disclose.