by Steven Sandberg-Lewis, ND, DHANP

The following is one of the key chapters from my soon-to-be published book Let’s Be Real About Reflux: Getting to the Heart of Heartburn. My new book is not another “it’s all about too much acid” rehash of misconceptions about heartburn. It provides a fresh approach to understanding the multiple causes and presents a thorough explanation of evidence-based lifestyle hacks and natural medicine treatments.

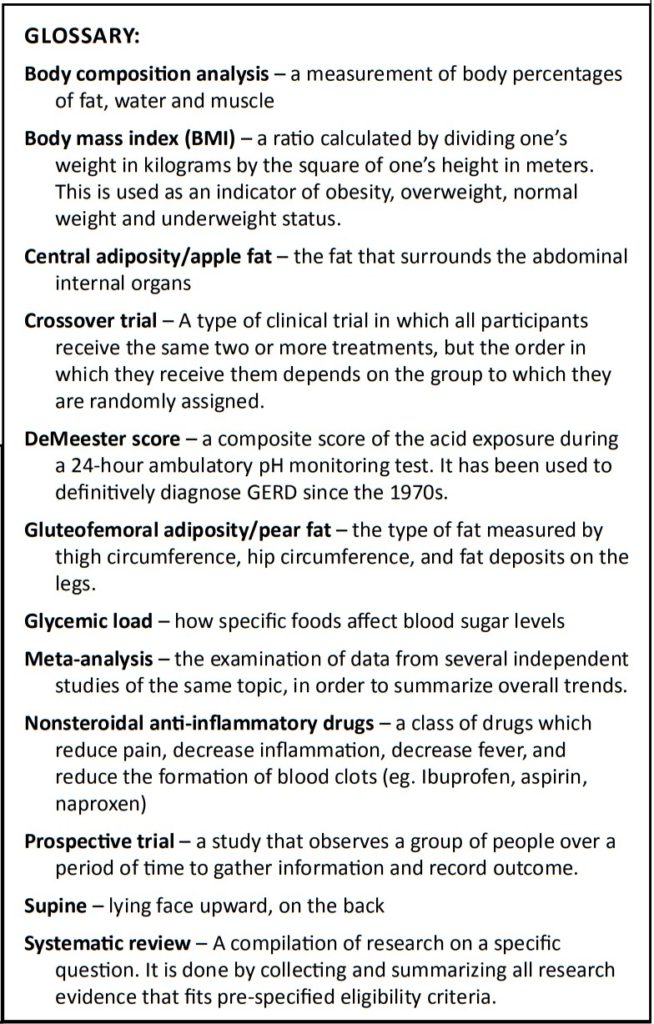

“Reduce CARBs: Relieve Reflux” presents a mnemonic for lifestyle-based approaches any one of which may significantly reduce heartburn depending on an individual’s underlying reflux etiology and personal habits.

Each chapter has a glossary of terms and is written so both those with medical training and those without can benefit from reading.

TABLE OF CONTENTS for

Let’s Be Real About Reflux

- How the Upper Digestive System Should Work

Anatomy & Physiology - Heartburn & GERD are NOT Synonymous

- The Common Symptoms of GERD

- IS IT GERD? Definitive Tests for Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

- How stomach acid is produced and suppressed

- Melatonin – More Than Just a Sleep Hormone

- What determines whether reflux leads to esophagitis?

- Treatment: Reduce CARBS: Relieve Reflux

- Treatment: Diets for Reflux

- Treatment: Natural Remedies for Reflux

- Your Brain May Be Sabotaging Your Digestion

- Hiatal hernia and hiatal hernia syndrome

- Helicobacter pylori may protect against reflux

- Hypochlorhydria and hyperchlorhydria

- Pancreatic Insufficiency

- Small intestine bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) and intestinal methanogen overgrowth (IMO)

- Bile reflux: the next valve down can reflux too!

- Complications of chronic reflux – Barrett’s esophagus

- Reflux in Kids

- Reflux and sex

Chapter 8 –

Common Lifestyle Factors Promoting GERD

Below is a mnemonic device to list the more important lifestyle factors that can trigger or increase heartburn and other reflux symptoms. It is unlikely that they are all significant triggers for any one person, but one or more may be important. People with reflux may choose to avoid these various foods, drinks, drugs (check with your doctor before making any changes to your prescription medications) or activities. Removing one factor at a time while monitoring symptoms has resulted in heartburn relief for many people.

The mnemonic is “Reduce CARBS, Relieve Reflux”

C – cola (soda in general), coffee, chocolate, cigarettes (tobacco in general)

A – alcohol, acidic foods, aspirin (and other over-the-counter pain and inflammation medicines)

R – refined carbohydrates; excess carbohydrate intake, even unrefined such as whole grains or starchy vegetables (see Chapter 9 for more dietary details); rapid eating; Rx (certain prescription medicines discussed in Chapter 1)

B – big meals (eating too much at a meal); bigger waist circumference; bedtime eating/eating within 3 hours of going to bed

S – snacking; sleeping position; shallow chest breathing; saturated fat, (high intake of any type of fat); spicy food; sensitivity to specific foods

The above is your mnemonic. Here is more detail.

Cola and other soda – The Melbourne Collaborative Cohort Study is a large prospective trial that found carbonated beverages increased the risk of GERD in both men and women (Wang SE, 2021). Agrawal, (2005) found carbonated soft drinks were highly acidic and caused almost immediate acid pH in the lower esophagus. Another study found that although extreme acidity lasted only 90 seconds, an acid pH of less than 4.0 could persist as long as 13 minutes after exposure (Shoenut JP, 1998). Others speculate that carbonated drinks cause more distention of the stomach, increasing intragastric pressure which may cause laxity of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES), the anatomical safeguard against reflux. Perhaps the best evidence of a mechanism of carbonated beverages causing reflux comes from Pouderoux et al. Their research found that carbonated rather than distilled water increased the retention of food and liquid in the gastric fundus, where stomach contents would have the most reflux potential.

Coffee – Drinking espresso, filtered coffee or instant coffee all significantly raise serum gastrin levels within 15 minutes of consumption. This effect on gastrin, a potent stimulator of acid production by the parietal cells in the body of the stomach, wears off after about an hour (Papakonstantino E, 2016). A meta-analysis of 15 studies found that the symptom of heartburn did not correlate with coffee consumption, whereas the presence of erosive esophagitis on upper endoscopy did (Kim J, 2014). There are commercial acid-free coffees that taste like regular coffee, which may be less likely to trigger GERD.

Chocolate – According to Surdea-Blaga et al, chocolate induces reflux and increases the lower esophageal exposure to acid. Research published at Stanford University adds that chocolate reduces lower esophageal sphincter pressure (Kaltenbach, 2006).

Lifestyle-based approaches can significantly reduce heartburn.

Cigarettes – A meta-analysis of smoking as a risk of Barrett’s esophagus found a consistent association. The greater number of packs per day over years of smoking increased the risk (Andrici J, 2013). In smokers, laryngopharyngeal reflux symptoms and upper endoscopy findings significantly improved after two months of tobacco cessation (Dinc ASC, 2020). Kahrilas reports that smokers have chronically diminished LES pressure and smoking increases the rate of reflux events. The most important mechanisms are thought to be decreased effectiveness of saliva in clearing refluxed material from the esophagus as well as increased intra-abdominal pressure.

Alcohol – Alcohol consumption can reduce the LES pressure, which facilitates reflux. Alcohol also has a direct toxic effect on the esophageal mucosa, predisposing to acid/pepsin injury (Ness-Jensen E, 2017). German researchers report that alcohol use reduces the strength of contraction of the lower esophagus leading to decreased clearance of refluxed material (Franke A, 2005). These effects also increase the risk of esophageal cancer. A meta-analysis of twenty-nine research studies found that any regular use of alcohol increases the rate of reflux by just under 50% compared to non-drinkers or occasional drinkers. Alcohol use is more of a risk for erosive esophagitis rather than for non-erosive reflux disease (Pan J, 2019).

Acidic foods – The consumption of citrus fruit, vinegar, and tomato can either aggravate or ameliorate GERD. I often ask my reflux patients how they respond if they take a teaspoon of apple cider vinegar in two ounces of water just before a meal. Some get relief and others feel more burning and reflux symptoms. My theory is that patients with erosive esophagitis or gastritis are more sensitive to the acidity of vinegar and feel it as burning or pain. In addition, I theorize that those with hypochlorhydria and NERD often respond positively to the addition of vinegar, lemon juice, bitter herbs or betaine hydrochloride capsules taken with meals. A 2018 Italian study found that daily intake of citrus fruit and tomato along with a sugar-free diet was effective in treating GERD. They suggest that the acids in lemon, orange, and tomato lowered the pH of the stomach which reduced the production of gastrin and therefore hydrochloric acid, relieving heartburn symptoms (Langella C, 2018).

Aspirin and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs – (NSAIDs) – A 2018 meta-analysis of ten research studies from around the world found a significant increase in reflux symptoms in people taking NSAIDs or aspirin (25.5%) compared to non-users (19.6%). These medications can also cause upper GI erosions and ulcerations. Aspirin is sold in both low dose (81 mg tablets) and regular dosage (325 or 500 mg tablets). A Japanese study of over 5500 people undergoing upper endoscopy compared subjects who took low dose aspirin compared to non-users, The incidence of erosive esophagitis was only 3% higher in the aspirin group, but there was a 10% higher risk for developing a peptic ulcer. According to Zographos et al, “aspirin disrupts the normal cytoprotective (cell protective) barrier in the mucosa of the stomach and a similar process has been found to occur in the esophagus… Esophageal emptying is slow in the elderly, resulting in a prolonged exposure of the mucosa to their irritant action. Nonsteroid anti-inflammatory drugs should be prescribed with caution in the presence of symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux.”

Refined and excessive dietary carbohydrates – A very low carbohydrate diet may be effective for reflux (Surdea-Blaga T, 2019). It was found to be significantly effective in eight obese subjects with GERD. 24-hour esophageal pH impedance testing was performed before and after a six-day diet containing less than 20 grams of carbohydrate per day. The DeMeester score for reflux dropped from an average of 34.7 to 14.0 (normal is less than 14.7). The percentage of time the esophageal pH was more acidic than 4.0 dropped by half (Austin GL, 2006). In another study, 33 obese white women and 9 obese black women followed a 16-week diet which was lower in simple and complex carbohydrate and higher in fat (saturated, polyunsaturated, and monounsaturated). The control group was 70 white women and 32 black women with comparable body types but no GERD symptoms (Pointer SD, 2017). Prior to the dietary intervention, the women with GERD ate a diet with a higher glycemic load, which included more total carbohydrate, sucrose, total sugar, and starch. They had higher insulin resistance and inflammation markers. Body composition analysis, blood inflammatory markers, glucose, and insulin as well as GERD symptoms and use of GERD medications were monitored during the study. The overwhelming result was that all the women with reflux had resolution of GERD symptoms within ten weeks and discontinued their reflux medications. The white women had the highest carbohydrate intakes prior to starting the study and had the greatest reduction in insulin resistance by following the 16-week low carbohydrate diet. All the women lost similar amounts of weight.

Certain indigestible forms of carbohydrate, such as psyllium seed powder or fenugreek fiber powder, may reduce reflux (DiSilvestro RA, 2011). A Russian study using a sucrose sweetened psyllium seed powder (five grams three times/day) found a significant increase in LES pressure and significant reduction in acidic and weakly acidic reflux episodes. Reflux time dropped in half (Morozov S, 2018). Some have suggested that the gel that forms when psyllium fiber is mixed with water may create a barrier which prevents reflux. It is interesting that fenugreek is also used in traditional medicine for insulin resistance since this is also a risk factor for GERD (Zhou C, 2020).

Rapid eating – Increased numbers and duration of transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations (TLESRs) are thought to be an important cause of GERD. TLESRs are triggered when the stomach is distended by solids, liquids and/or gas and the LES opens for longer periods of time than needed to allow food to pass. Remaining open permits the venting of pressure and gas. A study of 20 normal adults (13 women and 7 men without reflux) measured the difference in 24-hour pH impedance results between identical meals eaten either in five minutes or eaten in thirty minutes (Wilde SM, 2004). The two test meals were spaced a day apart. A significant increase in the number of reflux events followed the five-minute meal compared to the thirty-minute meal. The increased reflux was predominantly non-acid in the first hour after eating and more acidic in the second hour. Of note: An earlier study showed that subjects with hiatal hernia had twice the number of TLESRs, so a combination of rapid eating, larger meals and a hiatal hernia may be the most significant trigger for reflux (Kahrilas PJ, 2000).

Rx – Prescription Medications Causing or Increasing GERD

Asthma medications: albuterol (Ventolin, Proventil); metaproterenol (Alupent); pirbuterol (Maxair); terbutaline (Brethaire); isoetharine (Bronkosol); levalbuterol (Xopenex); salmeterol (Serevent).

Cardiac and hypertension medications: isosorbide mononitrate (Imdur, Monoket); isosorbide dinitrate (Isordil); propranolol (Inderal); amlodipine (Norvasc); diltiazem (Cardizem); felodipine (Plendil); nicardipine (Cardene); nifedipine (Adalat, Procardia).

Osteoporosis medications: bisphosphonates (Fosomax, Boniva and Actonel).

Additional drugs include the following:

• Tricyclic antidepressants: amitriptyline (Elavil); imipramine (Tofranil); desipramine (Norpramin); nortriptyline (Pamelor, Aventyl).

• Anticholinergics, such as atropine in Lomotil.

• Narcotics, such as morphine, oxycodone, Vicodin, etc. (sources differ on this effect)

• Sedatives, such as diazepam (Valium) and barbiturates.

Big meals (overeating) – Similar to rapid eating, large meals can distend the stomach enough to trigger more TLESRs and increase reflux symptoms.

Big waist circumference – Compared to lower weight adults, the odds of having GERD are three times greater in obese men and four times greater in obese women (Pointer SD, 2016). A study of 743 subjects in Taiwan found increasing waist circumference and body mass index (BMI) is associated with insulin resistance, rising blood sugar levels and GERD. These were most strongly associated in men (Hsu CS, 2011). Two meta-analyses found a positive association among increasing BMI, GERD symptoms and complications such as erosive esophagitis (Corley D, 2006 and Hampel H, 2005).

Of note, people with increased girth at the waist have a higher risk of GERD. Singh et al found that central adiposity (“apple fat”) leads to nearly twice the risk of developing GERD with erosive esophagitis than other body types (Singh S, 2013). In contrast, men with increased hip circumference or gluteofemoral (“pear-fat”) girth were protected against developing GERD symptoms, erosive esophagitis, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease as well as Barrett’s esophagus (Rubenstein JH, 2013 and Kendall BJ, 2016). The protective effect was not significant for women.

Bedtime meals – Eating within three hours of bedtime increases the risk of reflux by as much as seven and a half times (Zhang M 2021).

Snacks – A pilot study found that meal spacing for two weeks with no snacking resolved heartburn in 75% of subjects with erosive esophagitis. By eating two meals per day with only liquids between, the subjects were able to discontinue heartburn medication (Randhawa MA, 2015).

Sleep position – During the daytime, the average person produces over a liter of saliva. About every minute, the saliva is swallowed, bathing the esophagus in mildly alkaline fluid. This can help neutralize refluxed material from the stomach. During sleep, we swallow less frequently, and secrete less saliva. Research shows that esophageal acid clearance is significantly slower during sleep, even in studies of people sleeping upright!

In a recent study of 57 subjects, pH impedance testing was used to evaluate clearance of acid from the esophagus in various spontaneous sleep positions. Clearance was twice as fast sleeping on the left side compared to sleeping supine. Sleeping on the right side slowed the clearance even more than supine (Schuitenmaker JM, 2021). There is a reflux smartwatch app that can be used to train people to sleep on the left side. From homeopathic research we know that some sleeping on a wedge pillow or elevating the head end of the bed with blocks. “The four studies that reported on GERD symptoms found an improvement among participants in the head-of-bed elevation; a high-quality crossover trial showed a clinically important reduction in symptom scores at six weeks and less acidic esophageal pH readings. Although the researchers suspected some of the findings less reliable, they determined elevating the head of the bed to be a cheaper and safer alternative to drug interventions (Albarqouni L, 2021)

Shallow chest breathing – Eherer A., 2014 showed that training GERD patients to use diaphragmatic breathing can strengthen the LES. They conducted a randomized trial and used breathing exercises as the intervention. GERD patients using diaphragmatic breathing techniques were found to have fewer GERD symptoms as well as improved quality of life, better pH-impedance findings, and PPI use.

Saturated fat – There is a strong belief that consuming saturated fat increases GERD. While some studies have shown that fat increases perception of reflux and causes more symptoms in patients with gastroparesis (Homko CJ, 2015), a recent study of over 3000 Iranians using questionnaires to assess reflux and dietary fat found no correlation (Ebrahimpour-Koujan S, 2021). Overall, research on dietary fat is less conclusive that research on carbohydrate intake and GERD.

Spicy food – There are many variables in researching the effect of spicy food on reflux symptoms because individuals respond uniquely to the wide variety of spices. An Iranian questionnaire and symptom study of over 4600 men and women found high consumption of spicy foods was associated with a greater risk of heartburn in men, but not in women. The men eating spicy food more than ten times per week had three times more heartburn than men who did not eat spicy food. Occasional ingestion of chili may aggravate abdominal pain and burning symptoms whereas frequent, long-term use of chili in food has been found to improve functional dyspepsia and GERD symptoms (Gonlachanvit S, 2010).

Sensitivity to specific foods – Published case studies have shown that individuals have resolved LPR by removing specific foods to which they are sensitive (Vora A, 2021).

Steven Sandberg-Lewis, ND, DHANP, has been a practicing naturopathic physician since his graduation from the National University of Natural Medicine (NUNM) in 1978. He has been a clinical and didactic professor since 1996, teaching a variety of courses but primarily focusing on gastroenterology and GI physical medicine. His private practice is at Hive Mind Medicine in Portland, Oregon (www.hivemindmedicine.org).

Sandberg-Lewis is a popular international lecturer at functional medicine seminars, presents webinars and is frequently interviewed on issues of digestive health and disease.

In 2010 he co-founded the SIBO Center at NUNM which is one of only four centers in the USA for Small Intestine Bacterial Overgrowth diagnosis, treatment, education, and research.

He is the author of numerous articles and the column entitled “Functional Gastroenterology Bolus” in the Townsend Letter. His medical textbook is Functional Gastroenterology: Assessing and Addressing the Causes of Functional Digestive Disorders, Second edition, 2017. He is currently in the editing phase of Let’s Be Real About Reflux: Getting to the Heart of Heartburn, a book on underlying mechanisms and the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux. Website: functionalgastroenterology.com