Marianne Marchese, ND

Introduction

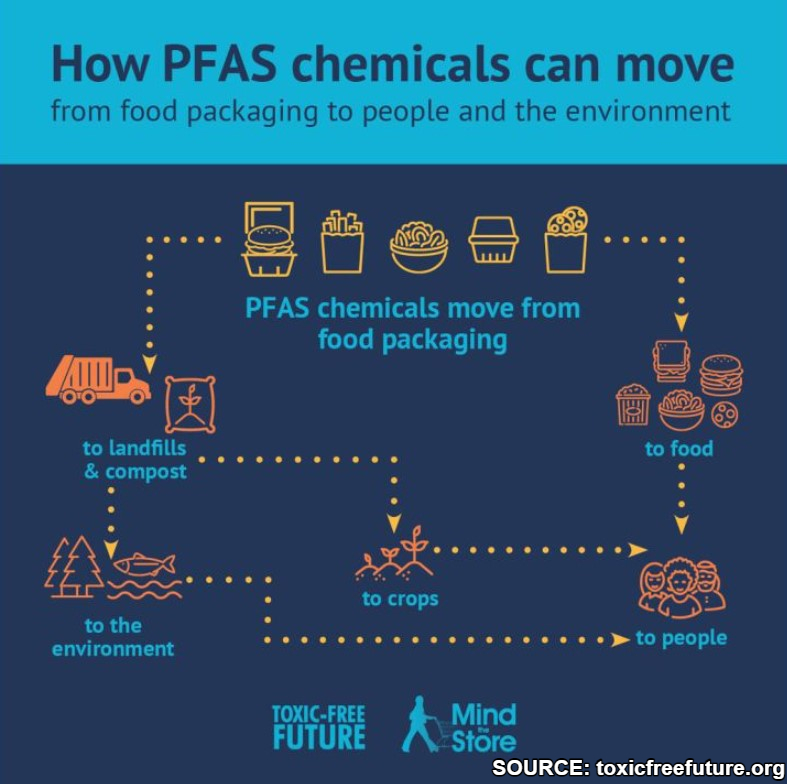

Perfluoroalkyl, perfluorinated chemicals (PFCs), and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are man-made chemicals known as forever chemicals because they don’t break down in the environment. Some chemicals that are in this group include perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS), perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA), perfluorohexane sulfonic acid (PFHxS), and perfluorodecanoic acid (PFDA). For simplicity’s sake we will refer to them in this article as PFAS. They are found in the air, soil, and water. They can accumulate up the food chain and be present in cooking and drinking water. They get into the environment from manufacturing, daily use of consumer products, and disposal of these products in landfills and incinerators. They don’t break down in the environment and can remain present forever.

Everyone is exposed to PFAS throughout the day and may not even realize their presence in food, products, clothing, and cookware. They are found in the blood of people all over the world. These chemicals are linked to adverse health effects, including cancer, reproductive and hormonal effects, cardiovascular disease, elevated liver enzymes, immune disruption, and more. Environmental groups and medical organizations have called for their regulation. The American Chemistry Council states PFAS are necessary and vital and resist regulation. So, is there a problem with PFAS?

PFAS Source of Exposure

PFAS are used in many consumer products to make them resistant to water, oil, heat, and corrosion. The chemicals in these products then contaminate water and the soil and can accumulate up the food chain. Some examples of where PFAS can be found include the following1,2:

- Non-stick pots and pans

- Waterproof and stain-resistant clothing and shoes

- Stain-resistant furniture, carpeting, and clothing

- Grease-resistant food packaging found in grocery stores and takeout food (pizza boxes, paper plates, food wrappers, salad bowls, takeout containers, paper bags, food liners, baking and cooking supplies to name a few)

- Ink used on food containers

- Machines that make packaging

- Paints and sealant

- Dental floss and shampoo

- Make-up and lipstick

- Cleaning products

- Firefighting foam

- Drinking water

- Contaminated fish

- Fertilizer that used industrial sludge

- Vegetables grown in or with contaminated soil, fertilizer, or water

- Contaminated wild game such as deer

Although the amount of exposure from each source may be small, we can be exposed to more than one source at a time and these chemicals build up in our body. We know this from various organizations performing bio-monitoring studies. The Center for Disease Control has been testing for the presence of PFAS in humans since 1999. People in the US participating in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) have their blood tested for the presence of PFAS. Most recently, CDC scientistsfound four PFAS (PFOS, PFOA, PFHxS, and PFNA) in the serum of nearly all the people tested.3

Everyone is exposed to PFAS to some degree, but some more than others. It appears that lower income communities have higher amounts of PFAS in their drinking water than other communities. A recent investigation in California discovered that disadvantaged areas have increased levels of PFAS in their drinking water compared to high income communities.4 In early 2019, California tested public water systems near PFAS sources of exposure to see if the water was contaminated. 1,300 drinking water sources in California were tested for 18 different PFAS, accounting for 3% of the state’s public water sources. 65% of the public water systems, serving over 16 million people, had high levels of PFAS. Disadvantaged communities had the highest levels in the state. California identified environmentally disadvantaged communities as those with higher rates of poverty and unemployment, higher pesticide uses in the area, and higher air pollution than the rest of the state.4 People most at risk for having PFAS in their drinking water are those living near chemical and product manufacturing sites, airports, military bases, landfills, wastewater treatment plants, incinerators, and areas where PFAS-contaminated sludge is spread on the soil.

After drinking water contamination, food packaging is probably the next largest source of exposure. Many people have no idea that the takeout food containers, food wrapping, and packing contain PFAS. Trying to test for PFAS in food packaging is a challenge since there are thousands of PFAS and testing can only identify a few dozen. One method to test for PFAS in food products and packaging is by measuring organic fluorine; this assesses the material’s total PFAS content. Denmark has recently set the limit at 20 parts per million (ppm). California is restricting the level to 100 ppm in 2023. Consumer Reports published results of the testing they conducted on 118 products. 37 products had fluorine levels above 20 ppm and 22 products were above 100 ppm.5 Paper bags contained 192.2 ppm, single use plates contained 149 ppm, and food wrappers/liners contained 59.2 ppm. Consumer Reports went on to test for organic fluorine, a measure of PFAS, in common fast food and supermarket takeout food packaging. The results are shocking. Here are a few of the findings.5

• Arby’s bag for cookies – 457.5 ppm

• Whole Foods market container for soup – 21 ppm

• Burger King wrapper for Whopper – 249.7 ppm

• McDonalds bag for French fries – 250 ppm

• Panera Bread container for pizza – 82 ppm

• Nathan’s Famous bag for sides – 876 ppm

Source: Toxicfreefuture.org

PFAS Health Effects

Since PFAS are present in the blood of over 90% of the population in the US and found in common consumer products, food, water and even found in the air, we need to understand the effects on human health. Studies show that PFAS affect men, women, and children. They have been linked to cancer, cardiovascular disease, infertility, thyroid disorders, weakened immunity, reproductive and development effects, liver disease and changes in hormones.6 Many argue that the concentration of daily exposure is so low that PFAS present in food, products and the water may not be at a high enough dose to cause health effects. Often, they are not seen as environmentally relevant in terms of health risk. However, even those who make that argument acknowledge that there is very little information on newer PFAS that we are exposed to or their precursors and degradation products. Many studies don’t take into consideration the synergistic effects of various forms and types of PFAS once in the body and the length of time these chemicals stay in the human body. In fact, there are very few studies on the safety of PFAS in small concentrations, or chronic low-dose exposure.7

What we do know does raise concern. PFAS have a very long half-life, are difficult to excrete and tend to accumulate in the body. Hence their presence in body burden studies mentioned above. In fact, PFAS have a half-life in human blood of 3-5 years.8 PFAS bind to blood proteinssuch as albumin and can be detected in blood, urine, breast milk, and plasma. They can accumulate in adipose tissue, liver, kidney, and the lungs.

The adverse health effects of PFAS have been known since the 1980s when PFAS were detected in the blood of workers who had occupational exposure. The female workers had high rates of birth defects in their offspring. Occupational exposure has also been linked to several forms of cancer such as bladder, kidney, and testicular cancer.9 Lower dose exposure has been linked to thyroid disease, altered kidney function, high cholesterol, ulcerative colitis, altered immune systems, and adverse effects on male sperm and female ovarian function.8 The Environmental Protection Agency acknowledges that high cholesterol is the most common adverse health effect from lower dose PFAS exposure. It appears that timing of exposure does matter. PFAS exposure in utero can have a negative impact on both the fetus and mother. In utero exposure is linked to hypertension during pregnancy, preeclampsia, and low birth weight babies.9

Researchers studying the health effects of PFAS are challenged by the numerous forms and mixtures, sources of exposure, geographical differences based on precipitation and wind drift, lack of an unexposed control group in the general population, various timing of exposures having different effects in utero, childhood, and adult years, as well as commercial laboratory testing variations.9 Despite these challenges, there is enough data on human health to warrant concern and for health care providers to start to educate on avoidance and begin testing patients for the present of PFAS. As stated earlier, the CDC NHANES program has been testing for PFAS in the blood of the general population since 1999 and over 90% of those tested had PFAS present. The levels are declining over time most likely based on awareness and avoidance education.

Regulation and Avoidance

It is important that health care providers focused on preventive medicine start to educate patients on how to avoid PFAS. Patient with health conditions linked to PFAS also need to implement avoidance measures at home, work, and school. It begins with testing the water that we drink and that we use for cooking. In 2009, the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) set a guideline for allowable levels of the PFAS chemical PFOA at 400 parts per trillion (ppt). In 2016 the agency reduced that level to 70 ppt. The EPA is currently reviewing the acceptable level of PFAS in the drinking water and will make a new proposal by the end of 2022 that will include both a non-enforceable maximum contaminant level goal and an enforceable standard as well. They will be proposing a PFAS National Drinking Water Regulation. It is important to note that real regulation will require preventing industries from contaminating our food and waterways with PFAS. In 2022 the EPA did begin steps to address PFAS contamination leaching from fluorinated containers and the EPA removed two PFAS from its Safer Chemical Ingredients list. Some states, such as California, are taking matters into their own hands by restricting PFAS in food packaging and creating tight regulating of levels of PFAS in the drinking water.10 These are important steps but, in the meantime, people need to be educated on avoidance measures.

Avoidance Measures

- Avoid non-stick cookware other than ceramic.

- Use stainless steel, cast iron and glass cookware.

- Avoid microwaveable popcorn bags that may be coated with PFAS.

- Cook at home to avoid to-go containers.

- Transfer food out of packaging as soon as you get it home to glass containers.

- Avoid reheating food in takeout containers.

- Avoid products, furniture, carpet, and clothing labeled as no-iron, stain-resistant, waterproof, non-stick, easy clean.

- Test your water and report PFAS to local water regulating agencies.

- Use a reverse osmosis or charcoal water filter for all drinking and cooking water.

- Look for products labeled as PFAS-free.

- Choose restaurants working to phase out PFAS from takeout containers.

- Avoid cosmetics labeled as water-resistant or that contain “fluoro” in the ingredients.

- Use HEPA-type air filter at home and work

- Use a vacuum with HEPA filter

- Continue to stay educated and informed about PFAS source of exposure, health effects and regulation

Summary

Perfluoroalkyl, PFCs, and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are man-made chemicals that include perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS), perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA), perfluorohexane sulfonic acid (PFHxS), and perfluorodecanoic acid (PFDA). They are present in our drinking and cooking water, food packaging and containers, cosmetics, clothing, furniture and home furnishings, indoor and outdoor air, cookware and numerous other places. The majority of people in the US are exposed to low dose PFAS—often without knowing they are exposed. Body burden studies confirm over 90% of the population has detectable levels of PFAS in the blood. These chemicals are harmful to human health even in low doses. It is vital that health care professionals consider PFAS exposure as a link to adverse health conditions, have patient test their home water for PFAS, and educate people on how to avoid PFAS in their daily life.

Dr. Marianne Marchese is the author of the bestselling book 8 Weeks to Women’s Wellness about the environmental links to women’s health and how to mitigate the effects from toxicants. She maintains private practice in Phoenix, Arizona, and is adjunct faculty at SCNM, teaching both environmental medicine and gynecology. She lectures throughout the US and Canada on women’s health, environmental, and integrative medicine topics. Dr. Marchese recently helped develop three supplements for Priority One Vitamins. www.drmarchese.com

References

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR). Per-and polyfluoroalkyl

Substances and Your health. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human

Services, Public Health Services. www.atsdr.cdc.gov/pfas. Accessed May 31, 2022. - O’Brien K. Forever chemicals upended a Maine farm — and point to larger problem.

Washington Post. April 11, 2022. - Center for Disease Control. per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) factsheet. May

2nd, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/biomonitoring/PFAS_FactSheet.html. Accessed June 8,

2022. - Reade A, Lee S. CA PFAS Pollution Widespread in Disadvantaged Communities. NDRC.

Aug 17, 2021. CA PFAS Pollution Widespread in Disadvantaged Communities | NRDC.

Accessed June 6, 2022. - Loria, K. The Dangerous Chemicals in your Fast-Food Wrappers. Consumer Reports. May

- 36-43.

- Our Current Understanding of the Human health and Environmental Risks of PFAS.

Uniter States Environmental Protection Agency. March 16, 2022. https://www.EPA.gov/

pfas/ Accessed June 19, 2022. - Sinclair GM, Long SM, Jones OAH. What are the effects of PFAS exposure at

environmentally relevant concentrations? Chemosphere. Nov 2020;258:127340. - Calvert L, et al. Assessment of the emerging threat posed by perfluoroalkyl and

polyluoroalkyl substances to male reproduction in humans. Front Endocrinol

(Lausanne). March 9, 2022;12:799043. - Blake BE, Fenton SE. Early life exposure to per- and polyfluroalkyl substances (PFAS) and

latent health outcomes. Toxicology. Oct 2020;443:152565. - EPA continues to take actions to address PFAS in Commerce. March 16, 2022. https://

www.epa.gov/newsreleases/ Accessed June 22, 2022