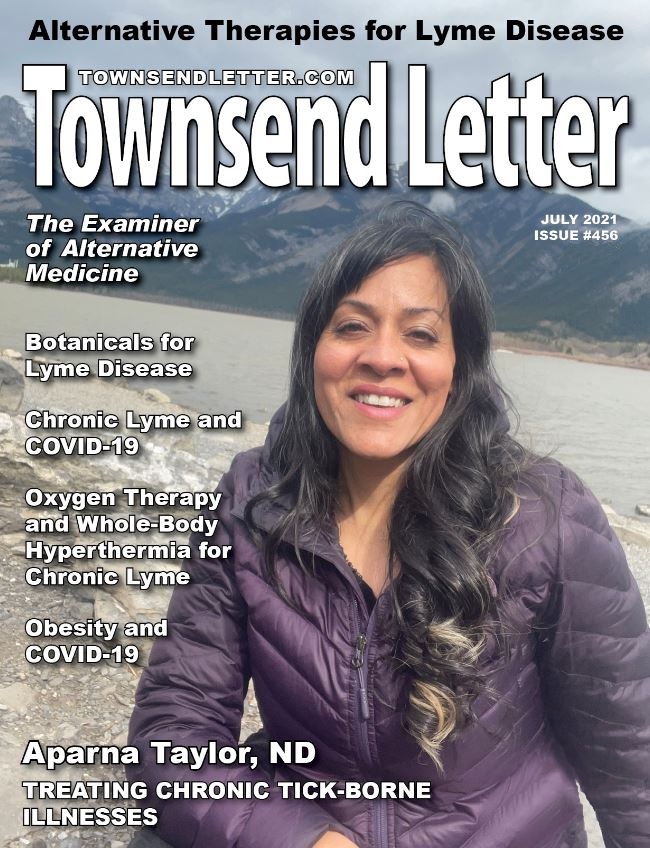

By Aparna Taylor, ND

In Alberta, one of the things I am grateful for is the ability to enjoy the wilderness and Rocky Mountains. Year round, there are many activities to explore—some with minimal planning, such as short, day hikes, or some more involved such as camping. As I start preparing for camping in the backcountry this summer, I go back to the fundamental steps that provide the framework, which will encourage a successful experience for the kids and us as well. Having an organized system ahead of time is a valuable tool—whether planning a family vacation or treating complex medical conditions.

When treating chronic tick-borne illnesses, having fundamental steps to follow can establish a framework and provide a compass to navigate progress.

Each clinician will have a set of tools that feel more familiar (like the Leatherman or Swiss army knife); and with the multitude of diagnostic and treatment options out there, grounding with the fundamentals will direct the use of these tools to what resonates with an individual practitioner and his or her patient.

Following these principles, diagnosing and treating patients can be individualized, while being practical and following your own strengths as a practitioner.

While it may seem the first question should be how to diagnose chronic infection(s), my bias is to place the focus on what concerns the individual first. This takes away the risk of placing all symptoms under the umbrella of an infection as the cause, when this may not be the case. Many symptoms overlap with chronic infection(s); focusing on the patient first will bring attention to how there may be multiple causes for the presentation of symptoms.

We can break the steps into 10 fundamental questions:

- What symptoms affect your patient the most?

- Is there a diagnosis that fits?

- Are there other diagnoses that may contribute to the symptoms? Are they managed appropriately?

- Are your patient’s ailments caused by an infection? Is that infection a chronic tick-borne disease?

- Does your patient have a clear diagnosis, or is it muddled?

- Do you have testing to support or rule out your diagnoses?

- How do you diagnose Lyme and tick-borne diseases?

- How do you treat?

- What if they don’t improve?

- What is important to your patient?

As with planning for a camping trip, reviewing the steps of an organized system before forging into the forest helps to prepare for the journey ahead. The following is a further breakdown of the 10 steps to consider when diagnosing and treating Lyme and tick-borne infections.

What symptoms affect your patient the most? This may seem elementary, and it is. What bothers the patient most will provide a compass to which system may be most affected. In a condition that can have multiple system involvement, while there may be other pressing concerns, identifying this one will also ensure your patient will have their immediate needs brought to the surface. Most patients have complex symptoms and co-morbidities. Identifying these will help understand whether the symptom overlaps, is amplified by, or is consistent with what is on your differential list of diagnoses. This allows for consideration of a root cause that may be different than infection(s).

Is there a diagnosis that fits? Lyme and associated diseases masquerade and travel to multiple areas of the body, changing the pattern of illness or discomfort over time. While most abnormal symptoms end up on lists associated with these conditions, infection may not be the only cause. If the presentation of symptoms fits very clearly with a diagnosis to explain a disease process, that diagnosis then would follow the typical pattern accepted for treatments offered.

In some cases, vague presentations can represent chronic infection, though may not be tick-borne. I met Diane* (*not her real name) for an assessment to rule in or rule out Lyme or related infections. She reported a history of vague exposure risk for tick-borne illness, though had migrating joint pains, headache and neck pains, extreme bouts of fatigue, and general feelings of malaise. We did a thorough exam of her history, onset of symptoms, and interventions that were even mildly effective, along with identifying other contributing factors that may be independent of her symptoms. Testing revealed that she did have a chronic infection, with a low CD 57 count, though her Borrelia Elispot was zero, indicating her T cells were not reactive to proteins on the bacteria. While this test is indirect, (looking for evidence of the bacteria and not the bacteria itself) and the testing is supportive, not solely diagnostic of a clinical diagnosis and history, the onset of significant symptoms began after she had a tooth abscess. She had followed up initially and was reassured this was not the cause, leading her down the path of other causes such as Lyme disease. Upon further investigation (and referral to a different dental specialist), it was determined the abscess was still chronically active; and after a follow up surgery and support, her symptoms resolved.

Most of our complex patients are not this easily treated, though I highlight this intentionally. Upon seeing so many complex patients, there is a risk of developing a bias that complex testing and treatments (which add additional costs to patients out of pocket) will likely be the path towards cure or management. I respectfully disagree. While there are times Occam’s razor may fail, with our increasing effort to understand health and disease, higher physician spending does not equal improved patient outcomes.1 While I do not discourage valuable investigations, there is a risk that unnecessary and costly investigations can complicate identifying the root cause. In the US, despite a higher cost and health care spending, several measures of population health showed far worse outcomes and prevalence of chronic diseases compared to the other international countries studied, compared to other developed countries.2 Spending more does not necessarily lead to better patient outcomes, and asking the question “is there a diagnosis that fits?” can help keep our focus on the possibility of the simplest answer being the correct one.

Are there other diagnoses that may contribute to the symptoms? Are they managed appropriately? With such vague and generalized symptoms, it can be confusing to tease apart which symptoms are related to which root cause, and to evaluate risk-benefit ratios with your patient in order to outline the options. Is fatigue and joint pain caused by a chronic tick-borne disease, or is it possible that hormones and digestive health are the cause?

Amit* (*not his real name) moved to Canada working as an engineer and spent much time outside in grassy areas inspecting equipment. He was concerned about the possibility of Lyme disease causing his symptoms. We evaluated his current work up, diet and lifestyle, previous labs as well as objective findings in physical exam. While his testing did not indicate current infection, he did have a poor diet with processed fast foods, low hydration, and high sugar and caffeinated beverages. His thyroid function was abnormal. We discussed the risk of possible interventions (including antimicrobials), and he agreed to work on his lifestyle. Within three-to-five weeks, his main symptoms decreased; and we reassessed his goals and options. He continued to improve without antimicrobials, particularly with extra support for hormones and his thyroid function and gut health.

I highlight this example to point out that an accurate diagnosis will respond to treatment, with improved symptoms also supported by objective findings. The risk of assuming treatment failure of antimicrobials or a complex plan may be a more aggressive or complex plan, which will not address the root cause(s). For most readers, these fundamentals may appear obvious; gut in practice, some of these patients have failed extensive investigations and treatments, have more harm from aggressive interventions that may be unnecessary, or need adjusting to manage appropriately.

Are your patient’s ailments caused by an infection? Is that infection a chronic tick-borne disease? If your patient has an acute infection, it will respond much more predictably to antimicrobials whether it is a tick-borne illness or other infection. A thorough history will reveal the onset of the symptoms, and factors contributing to this. If the infection is chronic or persistent, the complexity of correlation and causation of multiple factors increases, as well as the host’s own responses. A tool developed by Dr. R. I. Horowitz, MD, the Horowitz Multiple Systemic Infectious Disease Syndrome Questionnaire (HMQ), is a useful first step to differentiate those who may have Lyme disease from healthy individuals.3 Reviewing the results of this tool, which is free, clinicians and patients are able to evaluate how to proceed with further testing, which can be cost prohibitive as an initial step.

Does your patient have a clear diagnosis, or is it muddled? This is a reminder: In some cases individuals do have an obvious diagnosis, and while it may not be the question they are asking, asking this ourselves will encourage thoughtful and specific assessment when possible. The majority of the time, the diagnosis is more muddled. This distinction is valuable to identify with your patient as well, to relate back to the patient’s main concerns and ailments and help explain that there could be multiple and overlapping causes. Lyme and associated diseases can exhibit symptoms that are vague and muddle the diagnostic picture. Identifying other serious and complex medical conditions will clean the slate to assess which symptoms may be managed with interventions other than antimicrobials, and subsequently change the symptoms and support the patient’s overall health and prognosis, as much of the time, there are concurrent illnesses.

Do you have testing to support or rule out your diagnoses? While there is a division in the medical community regarding testing for Lyme and tick-borne diseases, there are valuable tests that offer objective values for a full clinical work up. Each clinician has a set of tools to work with and can individualize testing either with one lab or multiple labs. In Canada, the conventional testing is limited and out-dated, not considering other species, strains or co-infections, and is under-detected and under-reported.4 The merging of different disciplines with the goal of improving health outcomes (for example One Health5) or offering differing perspectives helps us to understand the variability between individuals and why there are challenges in using testing alone to diagnose these illnesses. While clinical diagnosis of Lyme disease is suggested,6 other objective findings with a comprehensive assessment of each individual is essential.

The diversity and diagnostic complexity of Lyme borreliosis7 requires each individual to be carefully vetted for the possibility of a different root cause, or multiple root causes. With the limitations of conventional labs, and complexity, including the biology of the bacteria and host co-morbidities, private labs offer information to fill some of these gaps; and I have used some from the USA (IGeneX, MDL) for testing—though currently work mainly with Arminlabs in Germany. Since most of these labs are an out-of-pocket expense for patients, when possible, we use conventional testing for other evaluations to provide information to help support or rule out differential diagnoses.

Each practitioner has a relationship with one or multiple labs and companies they use, and I encourage developing these relationships with the labs (there are others as well) to establish an organized system that resonates with your individual practice. Until the medical community can agree upon a universal assessment and collection of tests for diagnosis of Lyme and associated illnesses, and persistence of these infections, the controversy will continue. The biology of the bacteria is such that it is not easily detected in the bloodstream, thus indirect testing must be used. When choosing a lab, think about the science and whether it makes sense, and what the biases may be. While a clinical diagnosis is accepted with a comprehensive assessment,6 there is also a risk of bias and the potential for harm; thus, having a system can help to evaluate risk benefit ratios with patients regardless of the testing outcome.

How do you test and diagnose Lyme and tick-borne diseases? If using conventional testing, a diagnosis of Lyme or tick-borne disease may be missed.7 I suggest this be explored if possible, as in Canada, with a reactive conventional test and a positive diagnosis; further workup and evaluation may expand the medical support available under provincial healthcare, lowering costs to the patient. This unfortunately is not as common so a caution is not to assume a negative test rules out infection(s); it will only rule out what is tested for (either specific species/strains of Borrelia bacteria, or specific tick-borne infections).

If this appears to be an acute illness, then testing conventionally is limited since IgM antibodies will require two-to-four weeks to present in serology. I have used the T cell test (Borrelia Elispot from Arminlabs) within days of a presumed tick bite or new erythema migrans rash to rule out an acute response, which is extremely helpful. T cells are current, and thus while indirect, this test can help evaluate the risk-benefit analysis of treating whether a rash is present or not, after a potential exposure to a tick bite. Another important factor is to consider that geographical areas in Canada identified as endemic or non-endemic are changing8 due to a range of factors, including migrating songbirds9; this is also likely the case in other areas, including the United States. Even with the current T cell and other available tests, a full clinical workup is required to ensure the results are not interpreted in isolation. Another note is to be aware the erythema migrans rash, if present, may not appear as a “typical bull’s eye rash”10, 11

If the illness is chronic, all of the steps above are even more important to consider as tick-borne illness may be one but not the only cause or may not be the cause of the patient’s symptoms at all. Answering the question of root cause(s) is more difficult as the level of complexity goes up; some may be infectious, and some may not. The division within the medical community of whether or not symptoms are due to persistence of infection or other causes (eg, “Post-Treatment Lyme Disease Syndrome or PTLDS; auto-immune triggers similar to other sequelae post infection, such as campylobacter; Guillain-Barré syndrome; or other root causes) runs deep. This puts the clinician in a difficult position of trusting clinical findings and the patient’s history or providing recommendations that may restrict a diagnosis, leaving patients with only symptom management options. Humbly, I do not accept that individuals need to “live with it.” There is an answer to be sought, if questions are asked, based on the patient’s goals. A primary question to begin with is: could the symptoms be caused by an infection?

If so, how can we test for this? The MSIDS questionnaire helps to direct whether tick-borne disease may be the cause and warrant further testing, typically from more specific and sensitive private labs. There are other infections that can also contribute to chronic conditions, however, that may masquerade as one or another cause. If we remove the controversy and division in the medical community regarding chronic tick-borne diseases for a minute and evaluate this question, the investigation will focus on whether a chronic infection of any kind (bacterial, fungal, viral or other) could contribute to the patient’s presentation and trajectory of illness. While there are other testing methods (cerebral spinal fluid or synovial fluid from joints, brain imaging such as MRI to assess structure, and SPECT or PET images to evaluate function),12 there is not consensus of what the abnormalities observed are caused by; and it is unclear as with other testing, whether it is a correlation or causation. More importantly, these assessments are invasive and cost prohibitive for most individuals. Other investigations such as nerve conduction testing or skin biopsy may evaluate tissue level abnormalities but are not easily accessible to all and are not diagnostic.12

So how do we best answer the question? If other conditions have been ruled out, assessing first whether any infection may potentially cause some of the symptoms is valuable. While there is no one specific test to do this, each specialty lab will have panels to help differentiate the different organisms.

Tests that are available through provincial or state labs that are not out of pocket for patients will still provide some information, though may not be diagnostic for a specific condition. There is no one test that will identify every microbe; thus, it is up to each clinician to assess individually how to proceed. Since Borrelia have developed mechanisms, by way of tick’s salivary proteins, to evade host immune responses and induce anti-inflammatory cytokines,13 there are likely unique host immune responses to infection that conventional tests are not likely to detect, such as white blood cell counts or typical inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein, among others.

In many cases of Lyme disease, unlike in other infections, complete blood counts are largely normal.14 One way to evaluate whether a chronic infection such as Lyme disease is present may be to test a subset of natural killer cells, CD 57. While this is not diagnostic nor specific for Lyme disease, it has been observed by Stricker and Winger15 and is a valuable tool to answer the question of whether a chronic infection is present—though it still needs to be interpreted individually as viral infections, often present concurrently with Lyme and other infections, increase CD 57 numbers.16 In short, with the complexity of chronic infection(s) and individual co-morbidities, diagnosis still remains a comprehensive analysis of history, physical findings, and supported laboratory findings that result in a clinical diagnosis.

An invaluable tool is the guideline recommendations, which include assessments of evidence, put together by Cameron, Johnson and Maloney,17 a collective effort from the International Lyme and Associated Diseases Society (ILADS). This provides graded evidence for clinicians to assess each patient individually for Lyme disease, rather than a limited protocol for narrow criteria18 that would be applied to a heterogeneous population.

One area of controversy continues to exist, questioning the idea that symptoms that remain after treatment are not caused by infection; there is evidence to support persistence post treatment,19-30 and it is up to each individual clinician and patient team to evaluate how to proceed together to achieve wellness and address health goals. Testing and diagnosing is complex; thus, using only one step is not sufficient. A stepwise approach, with the questions outlined, will help to provide a guide for the many considerations that need to be individualized for each patient.

How do you treat? With such complexity and contributing factors, a comprehensive treatment plan is beyond the scope of this writing; likely this is understandable given the individuality of each patient’s health goals, co-morbidities, and ultimately which other infections may be involved, (some non-bacterial and not tick-borne). Immune dysregulation and chronic inflammation may influence which interventions are tolerated, as it is not uncommon for individuals to experience a cytokine storm or Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction31 when treating spirochetal infections with antibiotics. The pharmaceutical treatment considerations are outlined in previously mentioned guidelines,17 and some insight is provided to reconcile the conflicting treatment differences between ILADS and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) in the appendix of that document. These differences are not to be taken lightly, as under- or over-treating by length of time, potency, or number of antibiotics and other interventions without monitoring or assessment would have grave consequences. Additional learning that considers some of the complex factors with clinical application is available through ILADS, which is highly recommended.

My bias is towards practical and simple lifestyle changes, foundational to naturopathic and herbal medicine, if this resonates with the patient and his or her health goals, in addition to what is reviewed in the best available evidence. I begin with the first question above: what symptoms are affecting the individual the most? We discuss the risks versus benefits of options (pharmaceutical or non-pharmaceutical) that are available, based on the treatment principle we are trying to achieve. This process takes weeks at a minimum, with monitoring and assessment, then can take months with regular interval assessments—since most patients I have the privilege to meet have had complex and chronic health issues. This timeframe is influenced by how long the individual has been unwell, the number of infections and comorbidities, intensity of symptoms, and tolerance to treatment among other factors.

As the climate changes when weathering the elements in the backcountry, each individual adjusts and self regulates the layers covering their body. Multiple considerations also influence how a patient responds to treatment, with some layers being removed or added based on what else may be unpredictable in life. A considerable influence on the immune system is the impact of traumatic stress on the brain. Lasting changes in areas of the brain involved in the stress response have been found to alter structural and functional sequelae.32 It is known that psychological stress dysregulates the immune system,33 and that the interplay between the autonomic nervous and immune system involves complex steps that are integrated and mediated at multiple levels34—which may also influence the presentation of symptoms in patients with Lyme and related diseases. I highlight this, as supporting the parasympathetic nervous system with practical interventions (breath work, mindfulness, music, essential oils among many others) will encourage support of the immune system and may be some of the tools in the patient’s own toolbox to weather the storm (whether from cytokines or other).

How each clinician treats will resonate with the individualized approach based on the patient’s health goals and treatment principles devised together. The guidelines discussed17 are evidence based and focused primarily on pharmaceutical interventions. Other resources come from author’s experiences with conventional and natural approaches, whether from personal or clinical experience. How you treat will encompass your personal experience, training, and patient goals, as patients have chosen to see you for many reasons. How we treat is a continually evolving process based on the multiple factors discussed.

What if they don’t improve? This is a critical question, as the first diagnosis and treatment plan may be the easiest one. How the individual responds depends on multiple factors.

- Was the treatment the right one?

- Is more aggressive or longer treatment required, or less aggressive?

- Is a different treatment principle more fitting for now?

- Was the diagnosis correct?

- Are there other infections?

- Is there an obstacle to cure?

- Are there other confounding factors? (Mold, CIRS or biotoxin illness, trauma or mental health concerns, sleep disturbance, hormone imbalance, digestive disorder, heavy metal toxicity, malabsorption, food or medicine sensitivity, genetic mutations, among many others)

- Was the treatment too difficult to follow/lack of compliance?

Carefully revisiting all interventions and how they were followed, what the expected outcomes were, and what other considerations may be contributing is an often-overlooked missing piece that takes only one-to-three minutes to assess. Two books by Richard Horowitz35,36 offer reference guides that help navigate this overwhelming path.

If the outcome is not as intended, reviewing the above steps again may be tedious, though may also provide insight. While one root cause may be treated, with complex chronic conditions, there may be other aspects to consider, instead of only assuming it is still due to infection(s). Retesting with the lab of your choice is also reasonable, particularly if another infection may be contributing. If there is no improvement, rule out a new or missed condition in your differential diagnosis that may be one of the obstacles to getting better.

What is important to your patient? This question is not necessarily the final one, though it encompasses more than a foundational review of treating Lyme and tick-borne infections. While the primary goal of the clinician is to uncover the root cause(s) and help to achieve each patient’s health goals, what is most important to the individual may be obliquely understood or missed unless this is addressed. This may be different than the first question, “what symptoms bother the patient the most?”

In some cases, the obstacle to cure is obvious to a clinician (i.e., water-damaged home environment/biotoxins), though what is important and troubling to the patient may not be related to physical health specifically. Being able to devise a plan that works this important factor into the program may address not only physical imbalances but will also motivate the patient on deeper emotional, spiritual, as well as physical levels. What brings each patient to our practices may be how to diagnose and treat Lyme and associated diseases; we have an opportunity to create a space of nourishing care, not only with medical-related questions, but also questions about what they deem most important.

Fundamental steps and an organized system can be valuable tools that enable individualized care for each person. It can be easy to get lost in the wilderness without a map, so being able to refer back to these questions may support both clinician and patient when navigating these complex conditions. Navigation in the backcountry is an essential skill; and no matter what trail you end up on, tools such as a map and a compass help you get there. This still allows for pause while on the journey, to take in the environment, make adjustments, and as William Bateson said, “treasure your exceptions.” This journey with your patient is a collaborative one; and hopefully with these fundamental steps, the experience will be a successful one.

References

1. Tsugawa Y, et al. Variation in Physician Spending and Association with Patient Outcomes. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(5):675-682.

2. David Squires and Chloe Anderson, U.S. Health Care from a Global Perspective: Spending, Use of Services, Prices, and Health in 13 Countries (Commonwealth Fund, Oct. 2015).

3. Citera M, Freeman PR, Horowitz RI. Empirical validation of the Horowitz Multiple Systemic Infectious Disease Syndrome Questionnaire for suspected Lyme disease. Int J Gen Med. 2017;10:249-273.

4. Lloyd VK, Hawkins RG. Under-Detection of Lyme Disease in Canada. Healthcare (Basel). 2018;6(4):125. Published 2018 Oct 15.

5. One Health Basics. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Page last reviewed: November 5 2018. Accessed March 16 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/onehealth/index.html

6. Controversies & Challenges in Treating Lyme and Other Tick-borne Diseases. International Lyme and Associated Diseases Society. Accessed March 16 2021. https://www.ilads.org/research-literature/controversies-challenges/

7. Janet LH Sperling and Fleix AH Sperling. Lyme Borreliosis in Canada: Biological Diversity and Diagnostic Complexity from an Entomological Perspective. Can Entomol. 2009;141(6):521-549.

8. Ogden NH, et al. The emergence of Lyme disease in Canada [published correction appears in CMAJ. 2009 Sep 1;181(5):291]. CMAJ. 2009;180(12):1221-1224.

9. Scott JD, et al. Far-Reaching Dispersal of Borrelia burgdorferi Sensu Lato-Infected Blacklegged Ticks by Migratory Songbirds in Canada. Healthcare (Basel). 2018;6(3):89.

10. O’Malley M, Brown AG, Sharfstein JM. Looking for a bull’s-eye rash? Look again- erythema migrans can take many forms. Accessed March 29 2021. https://phpa.health.maryland.gov/OIDEOR/CZVBD/Shared%20Documents/Lyme_MD_poster_FINAL.pdf

11. Lyme Disease Basics for Providers. International Lyme and Associated Diseases Society. Accessed March 29 2021. https://www.ilads.org/research-literature/lyme-disease-basics-for-providers/

12. Diagnosis Lyme and Tick-Borne Diseases Research Center.Columbia University Irving Medical Center. Accessed March 29 2021. https://www.columbia-lyme.org/diagnosis

13. Iliopoulou, Bettina Panagiota; Huber, Brigitte T. Infectious arthritis and immune dysregulation: lessons from Lyme disease. Current Opinion in Rheumatology. July 2010;22 (4):451-455.

14. Krause PJ, et al. and the Deer-Associated Infection Study Group. Disease-Specific Diagnosis of Coinfecting Tickborne Zoonoses: Babesiosis, Human Granulocytic Ehrlichiosis, and Lyme Disease, Clinical Infectious Diseases. May 1, 2002;34 (9):1184–1191.

15. Stricker RB, Winger EE. Decreased CD57 lymphocyte subset in patients with chronic Lyme disease. Immunol Lett. 2001;76(1):43-48.

16. Nielsen CM, et al. Functional Significance of CD57 Expression on Human NK Cells and Relevance to Disease. Front Immunol. 2013;4:422.

17. Cameron DJ, Johnson LB, Maloney EI. Evidence assessments and guideline recommendations in Lyme disease: the clinical management of known tick bites, erythema migrans rashes and persistent disease. Expert Review of Anti-Infective Therapy. 2014; 12:9, 1103-1135.

18. Treatment for erythema migrans. Accessed April 10 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/postlds/index.html

19. Hodzic E, et al. Persistence of Borrelia burgdorferi following antibiotic treatment in mice. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008;52:1728–1736.

20. Hodzic E., et al. Resurgence of persisting non-cultivable Borreliaburgdorferi following antibiotic treatment in mice. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e86907.

21. Straubinger RK, et al. Persistence of Borrelia burgdorferi in experimentally infected dogs after antibiotic treatment. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1997;35:111–116.

22. Berndtson K. Review of evidence for immune evasion and persistent infection in Lyme disease. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2013;6:291–306.

23. Embers ME, et al. Persistence of Borrelia burgdorferi in Rhesus Macaques following antibiotic treatment of disseminated infection. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e29914.

24. Embers ME, et al. Variable manifestations, diverse seroreactivity and post-treatment persistence in non-human primates exposed to Borrelia burgdorferi by tick feeding. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0189071.

25. Crossland NA, Alvarez X, Embers ME. Late disseminated Lyme disease: Associated pathology and spirochete persistence posttreatment in Rhesus Macaques. Am. J. Pathol. 2018;188:672–682.

26. Feng J, et al. Biofilm/persister/stationary phase bacteria cause more severe disease than log phase bacteria—Biofilm Borrelia burgdorferi not only display more tolerance to Lyme antibiotics but also cause more severe pathology in a mouse arthritis model: Implications for understanding persistence, PTLDS and treatment failure. Discov. Med. 2019;148:125–138.

27. Schmidli J, et al. Cultivation of Borrelia burgdorferi from joint fluid three months after treatment of facial palsy due to Lyme borreliosis. J. Infect. Dis. 1988;158:905–906.

28. Häupl T, et al. Persistence of Borrelia burgdorferi in ligamentous tissue from a patient with chronic Lyme borreliosis. Arthritis. Rheum. 1993;36:1621–1626.

29. Middelveen MJ, et al. Persistent Borrelia infection in patients with ongoing symptoms of Lyme disease. Healthcare. 2018;6:33.

30. Sapi E, et al. The Long-Term Persistence of Borrelia burgdorferi Antigens and DNA in the Tissues of a Patient with Lyme Disease. Antibiotics (Basel). 2019;8(4):183. Published 2019 Oct 11.

31. Butler T. The Jarisch-Herxheimer Reaction After Antibiotic Treatment of Spirochetal Infections: A Review of Recent Cases and Our Understanding of Pathogenesis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2017;96(1):46-52.

32. Bremner JD. Traumatic stress: effects on the brain. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2006;8(4):445-461.

33. Morey JN, et al. Current Directions in Stress and Human Immune Function. Curr Opin Psychol. 2015;5:13-17.

34. Kenney MJ, Ganta CK. Autonomic nervous system and immune system interactions. Compr Physiol. 2014;4(3):1177-1200.

35. Horowitz, Richard I. Why Can’t I Get Better? Solving the Mystery of Lyme & Chronic Disease. New York: St. Martin’s Publishing Group; 2013.

36. Horowitz, Richard I. How Can I Get Better? An Action Plan for Treating Resistant Lyme and Chronic Disease. New York: St. Martin’s Publishing Group; 2017

Dr. Aparna Taylor has a love of nature and medicine and strives to help patients find a healthy balance on this journey. Growing up in Thunder Bay, Ontario, she received her biology degree from Lakehead University then took some time to volunteer in hospitals in India, travel, and became a yoga teacher. After this gap year, she moved to western Canada where she completed her master’s in muscle physiology and aging at the University of Calgary. While pursuing her PhD in molecular neuroscience, she re-awakened her passion for patient-centered medicine and moved to Toronto to study at the Canadian College of Naturopathic Medicine (CCNM) and become a naturopathic doctor.

One of her first patients in Thunder Bay inspired her to learn more about Lyme disease, and she was introduced to the International Lyme and Associated Diseases Society (ILADS). All of her experiences have provided tools to incorporate the principles of Eastern and Western medicine, yoga, and mindfulness to individualize regimens for each patient, based on health goals and informed decision making. Most of her practice is devoted to guiding patients who have chronic conditions, infections, and tick-borne illnesses. She believes that, fundamentally, a balanced approach that brings calm allows room for patients to heal. She shares her passion for learning, medicine, and community by teaching at seminars, conferences, and participating in research when she isn’t chasing and playing with her two young children and husband—all the while trying not to take herself too seriously.

.