By Elizabeth Shirley, RPh CCN

The gastrointestinal (GI) tract encompasses a complex balance of microbes, hormones, neurotransmitters, and enzymes. The health of our gastrointestinal system is dependent upon this balance and is extremely important for longevity and well-being. The GI system not only controls physical wellness, it also is integral to mental health. This is due to the gut-brain connection, the communication between the intestinal tract and the brain, which plays a critical role in our mental as well as physical well-being. Severe gut dysfunction could exacerbate the symptoms of brain disorders, significantly affecting quality of life.

The intestinal microbiome also influences metabolic and immune pathways, as well as genetic and epigenetic factors that shape all aspects of physiology. Disruption of the intestinal microbial ecosystem, known as dysbiosis, has major impacts in health. Dysbiosis has been associated not only with gastrointestinal, but also neurological, cardiovascular, respiratory, metabolic, and oncological diseases. Therefore, a rich, diverse intestinal microbiome is essential to our mental, intestinal, and overall health. Yet, according to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), five out of six individuals in the US receive one antibiotic prescription each year. This leads to alteration of the microbiome and increases dysbiosis.

A nitrate-rich diet, which supports the nitrate to nitrite to nitric oxide pathway, may help prevent dysbiosis and promote gastrointestinal health as well as support the gut-brain axis and maintain homeostasis. The highest nitrate-containing food sources include arugula (aka rocket), spinach, butter lettuce, bok choy, celery, and beets. Dietary nitrates and their metabolites are correlated with healthy oral, gut, and intestinal microbiota. Furthermore, nitrates may modulate inflammatory, immune, and oncological pathways. Nitrates also provide protection against toxicity induced by LPS (lipopolysaccharides), an endotoxin that increases proinflammatory cytokines and which is associated with a more permeable gut lining, leading to leaky gut. This paper will review the strong association of dietary nitrates and balancing nitric oxide levels with a healthy gastrointestinal tract. It will present the science showing that supporting healthy nitric oxide levels is an underutilized means of maintaining GI health.

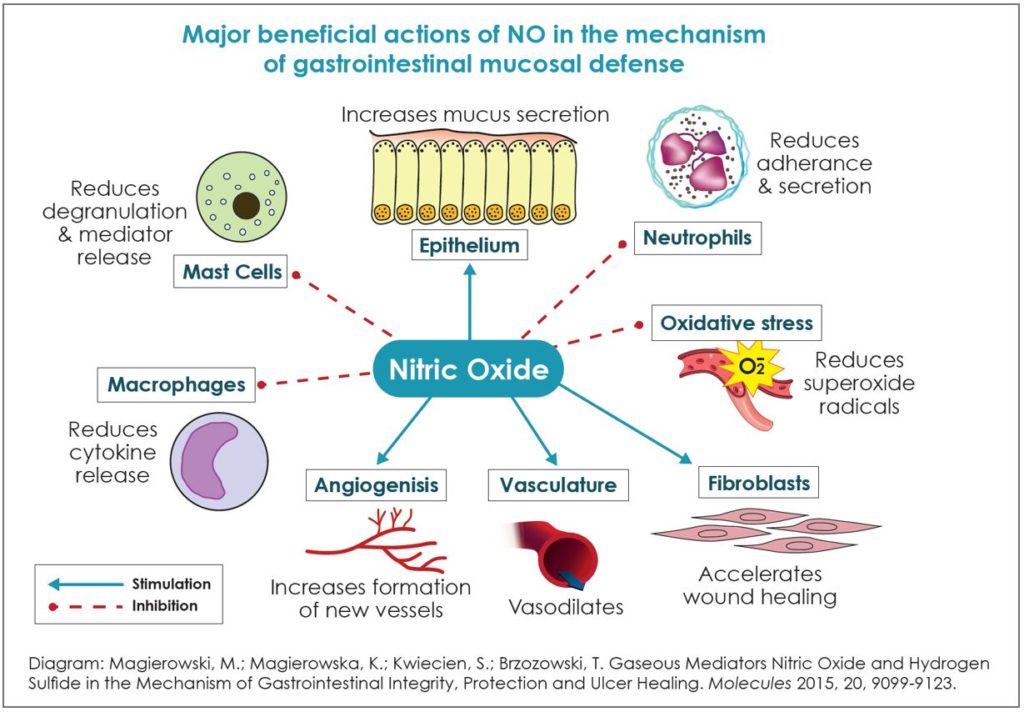

Nitric Oxide Protects the Gastric Mucosa

Having a healthy mucus layer is our first line of defense against pathogenic bacteria in our gut. It is a critical protective layer that balances good and harmful bacteria.1 Mucosa of the GI tract is continuously exposed to potentially damaging substances that can affect the gastric mucosal integrity. Ethanol, nicotine, drugs (e.g. NSAIDs), Helicobacter pylori, hyperosmolar solutions, bile salts, ischemia/reperfusion of gastric tissue, and chronic stress all can be causal factors in mucosal damage and gastric ulcers.2

Nitric oxide (NO) appears to be one of the most important signals for mucus secretion as it is the mediator responsible for cholinergic-stimulated mucus release.3 NO increases mucosal blood flow, which acts to dilute toxic substances, neutralize them, and remove them before they accumulate to damaging concentrations.3 Supporting the nitrate to nitrite to NO pathway increases mucosal blood flow and vasodilation, increases mucus production and thickness, modulates mucosal immune response, prevents acute peptic ulceration, and can even repair NSAID damage to the intestinal tract.3

Nitric Oxide and Intestinal Barrier Integrity

Tight junction proteins play a vital role in epithelial transport and are responsible for barrier integrity of the intestinal tract. Loss of tight junction proteins results in the breakdown of the intestinal barrier called leaky gut. There is decreased gastric expression of the tight junction proteins occludin and claudin 5 during dysbiosis. However, following nitrate consumption, both protein levels rebound.4

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) may play a vital role in homeostatic regulation of intestinal barrier integrity by affecting the expression of tight junction proteins.5 For example, decreased BDNF increases irritable bowel syndrome.5 BDNF also plays a role in depression, anxiety, learning and memory. It is important to note that NO is an essential mediator of BDNF activity.6

Antibiotics and Nitric Oxide

Broad spectrum antibiotics decrease microbial richness and diversity. The use of antibiotics has long been linked to intestinal disorders, leaky gut, and even mental health symptoms, including anxiety, depression, brain fog, and severe fatigue. Dietary nitrates have a supportive role to play during antibiotic treatment. Dietary nitrates taken during antibiotic therapy down-regulate gastric mucosal inflammatory pathways and prevent overt inflammation, and the resulting increased intestinal epithelial permeability.4 Nitrates may increase microbial biomass and act as a substrate for the existing microbial communities allowing them to thrive and prevent dysbiosis.

The oral microbiome may modulate the activities of the gut microbiome. Studies have shown that alterations in oral flora can cause an imbalance in the gut flora, which can increase the pathogenesis of gut disorders. It is known that 45% of the bacteria in the oral cavity and large intestine overlap, and we are constantly seeding the intestinal tract every time we swallow or eat.

Nitrates increase nitrate-reducing bacteria on the tongue and decrease levels of bacteria that are associated with poor oral health.7 Nitrate supplementation is able to prevent or reduce bacterial dysbiosis and stimulate eubiosis by increasing the beneficial, healthy bacteria and decreasing levels of disease-associated bacteria.8

Several recent studies have suggested that nitrite can be used as an alternative to standard antibiotic therapies owing to its ability to disrupt the protective biofilm formed by pathogenic bacteria.9 Furthermore, supporting the nitrate to nitrite to NO pathway ameliorates inflammatory cell infiltration, regulates microbial dysbiosis, and restores beneficial bacteria.10 Nitrates protect the gut microbiome under inflammatory conditions and restore local immune and inflammatory responses.

Nitrate, Nitrite, NO, Inflammation, and Immune Cells

A T cell is a type of lymphocyte and a helper T cell (TH) directs the immune response. Nitrates rebalance the ratio of TH cells in the peripheral blood. Nitrates also decrease proinflammatory TH1 and TH17, which are closely associated with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).9 Nitrates decrease IL17 in the colon, thus decreasing inflammation. IBD is a major risk factor for colorectal cancer, and nitrates may help prevent colitis and colorectal cancer.9 Additionally, nitrates increase Treg cells to maintain homeostasis and self-tolerance.

During inflammatory events, there is increased expression of myeloperoxidase, which is involved in the antimicrobial response by increasing reactive oxygen species (ROS). Another way in which nitrates and NO support a healthy inflammatory response in the GI tract is by decreasing myeloperoxidase activity in gastric mucosa.4

Furthermore, nitrite and NO can regulate the activity of mast cells.11 Mast cells are white blood cells that are part of the immune system and function as a bridge between the immune and nervous system. Mast cells modulate the inflammatory processes in depression, anxiety, brain fog, and insomnia.12 Mast cells become activated in the absence of NO production, and increased superoxide production contributes to mast cell activation.11 Conversely, nitrites and NO are an effective inhibitor of mast cell dependent inflammatory events. Nitrites and NO suppress antigen-induced degranulation and mediator release, including histamine and cytokine expression.11 In addition, nitrites and NO inhibit leukocyte endothelial cell attachment and inhibit generation of ROS by mast cells.11

Reducing the Effects of Stress on the GI Tract

Mast cells are important effectors of the gut-brain axis by translating stress signals into release of neurotransmitters and proinflammatory cytokines. Chronic stress causes inflammation and damage to all cells in the body, including in the GI tract. Stress can cause the following:13

- Alter GI motility,

- Change GI secretion,

- Increase intestinal permeability,

- Decrease regenerative capacity of GI mucosa and mucosal blood flow,

- Have negative effects on intestinal microbiota, and

- Inhibit production of NO through the arginine/NOS enzyme.

Supporting the GI tract with nitrates addresses these multiple adverse effects of stress. Furthermore, nitrate and replenishing NO levels can enhance mental health, leading to improved sleep, less anxiety, and less symptoms of depression, thereby affecting factors that can indirectly lead to impaired GI health.14

Can Nitric Oxide Really Damage the GI Tract?

It is controversial whether the increased NO from iNOS, or any other source, causes GI injury, and there are questions about the role of peroxynitrite in the production of tissue injury.3

The use of L-NAME (nitro-l-arginine methyl ester), an iNOS inhibitor, which leads to some decrease of tissue injury and inflammation, may not be due to inhibition of the production of cytotoxic concentrations of NO.3 There are other actions of L-NAME that may be at play here.15 Administration of large amounts of NO does not cause detectible damage to the mucosa or vasculature of the intestine, and the majority of available data point to NO serving a critical role in protecting the GI mucosa from injury induced by ROS and other cytotoxic substances.3,16

Conclusion

Dietary nitrates clearly play an important role in protecting GI health. Nitrate inhibits the inflammatory process and down-regulates and scavenges oxidative stress. Furthermore,

nitrate is a powerful modulator of the microbiome, and microbiome diversity is the foundation for health and longevity.

A nitrate-rich diet, which supports the nitrate to nitrite to nitric oxide pathway, may help prevent dysbiosis, promote a healthy gut-brain axis and therefore support both gastrointestinal and mental health, and maintain homeostasis.

Beth Shirley, RPh, CCN developed an expertise as a pharmacist and board certified clinical nutritionist during a 40+ year career. Her specialities include stress-induced hormonal imbalance, intestinal dysfunction, autoimmune and chronic inflammatory issues, detoxification, nutrigenomics, and super-normal oxidative stress.

Over the last 12 years, Beth has spent time working with some of the leading thought leaders in the world of nitric oxide research and through this has developed an in-depth knowledge on the topic and its potential applications in patient care. She currently is the executive director of the Berkeley Life Scientific Advisory Board.

References

1. Herath M, et al. The Role of the Gastrointestinal Mucus System in Intestinal Homeostasis: Implications for Neurological Disorders. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2020;10:248.

2. Magierowski M, Magierowska K, Kwiecien S, Brzozowski T. Gaseous mediators nitric oxide and hydrogen sulfide in the mechanism of gastrointestinal integrity, protection and ulcer healing. Molecules. 2015;20(5):9099-9123.

3. Kubes P, Wallace JL. Nitric oxide as a mediator of gastrointestinal mucosal injury?-Say it ain’t so. Mediators Inflamm. 1995;4(6):397-405.

4. Rocha BS, et al. Inorganic nitrate prevents the loss of tight junction proteins and modulates inflammatory events induced by broad-spectrum antibiotics: A role for intestinal microbiota? Nitric Oxide. 2019;88:27-34.

5. Yu YB, et al. BDNF modulates intestinal barrier integrity through regulating the expression of tight junction proteins. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;29(3).

6. Cheng A, et al. Nitric oxide acts in a positive feedback loop with BDNF to regulate neural progenitor cell proliferation and differentiation in the mammalian brain. Dev Biol. 2003;258(2):319-333.

7. Walker MY, et al. Role of oral and gut microbiome in nitric oxide-mediated colon motility. Nitric Oxide. 2018;73:81-88.

8. Rosier BT, et al. Nitrate as a potential prebiotic for the oral microbiome. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):12895.

9. Hu L, et al. Nitrate ameliorates dextran sodium sulfate-induced colitis by regulating the homeostasis of the intestinal microbiota. Free Radic Biol Med. 2020;152:609-621.

10. Rocha BS, Laranjinha J. Nitrate from diet might fuel gut microbiota metabolism: Minding the gap between redox signaling and inter-kingdom communication. Free Radic Biol Med. 2020;149:37-43.

11. Coleman JW. Nitric oxide: a regulator of mast cell activation and mast cell-mediated inflammation. Clin Exp Immunol. 2002;129(1):4-10.

12. Graziottin A, Skaper SD, Fusco M. Mast cells in chronic inflammation, pelvic pain and depression in women. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2014;30(7):472-477.

13. Konturek PC, Brzozowski T, Konturek SJ. Stress and the gut: pathophysiology, clinical consequences, diagnostic approach and treatment options. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2011;62(6):591-599.

14. Shirley B, RPh CCN. Nitric Oxide and Mental Health. Berkeley Life. https://lifes2good.box.com/s/hgnwjkuloyztytvz97o0magqrzreihy4. Updated June 2020. Accessed February 3, 2021.

15. Kubes P, et al. Nitric oxide synthesis inhibition induces leukocyte adhesion via superoxide and mast cells. Faseb j. 1993;7(13):1293-1299.

16. Weitzberg E, Hezel M, Lundberg JO. Nitrate-nitrite-nitric oxide pathway: implications for anesthesiology and intensive care. Anesthesiology. 2010;113(6):1460-1475.