…article continued:

Patients with chronic insomnia are often prescribed sleep medications, which are needed in many cases when they cannot fall asleep and remain asleep with consistency. Inadequate sleep will add to the burden of allostatic load (AL) and allostatic overload (AO) and result in durable and adverse brain changes that are unlikely to be reversible with treatment. The most commonly prescribed sleep medications include specific benzodiazepines (i.e., estazolam, flurazepam, quazepam, temazepam and triazolam), which typically have half-lives of over eight hours (except for triazolam).109 The problems with this class of medication are numerous and include “next-day (residual) fatigue, psychomotor and neuropsychological dysfunction” (p.2).109 Additional problems involve dependence, withdrawal and rebound symptoms when they are abruptly discontinued, and the potential for abuse especially among vulnerable patients with prior alcoholism and drug abuse.109

There is another class of sleep medication known as the non-benzodiazepines (“but also benzodiazepine receptor agonists”) that “selectively attach to the benzodiazepine recognition site on the GABA-A receptor” at the level of the alpha-1, or alpha-2, and/or alpha-3 subtypes (pp.2-3).109 Sleep medications in this class, known as Z-drugs, include Zaleplon, Zolpidem, and Eszoplicone. Even though they have shorter half-lives compared to benzodiazepines (i.e., 8 hours or less) they still have a spectrum of adverse effects that are similar to benzodiazepines and include “sedation, anterograde amnesia, complex sleep-related behaviors, and impaired balance with subsequent falls” (p.3).109

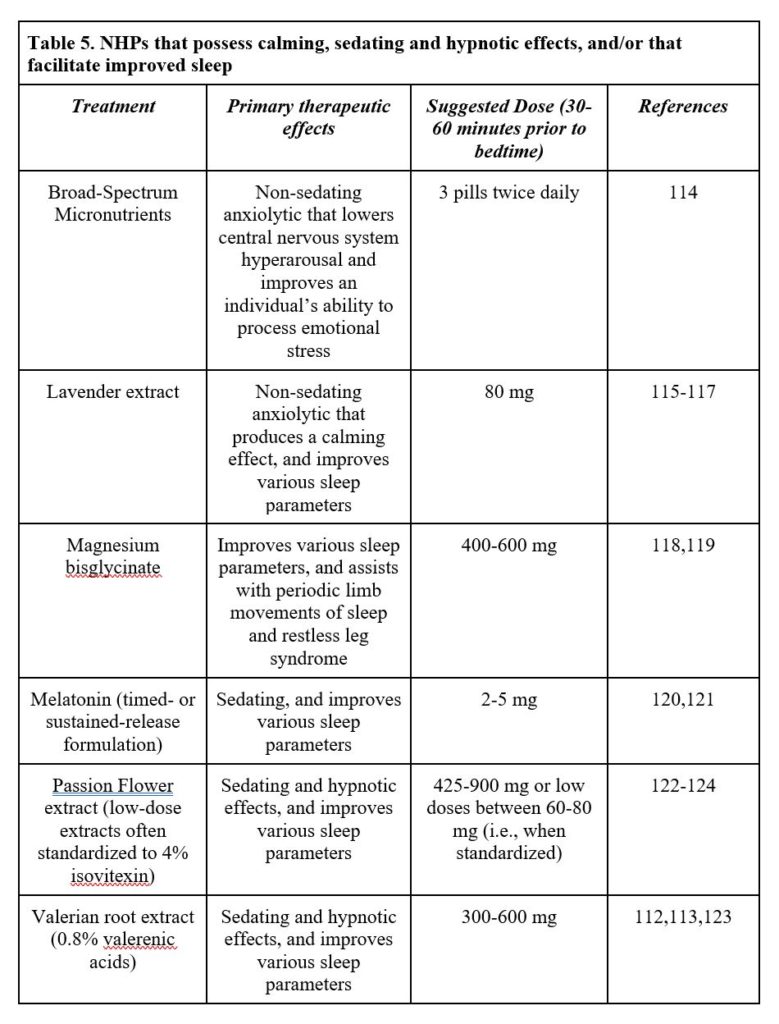

Given how serious these adverse effects are, it is preferable to recommend specific natural health products (NHPs) (Table 5) as first-line treatments since they do not possess similar dependence, withdrawal, and rebound symptoms, and do not appear to be associated with abuse. Among all the NHPs noted, there is data demonstrating that melatonin may assist with benzodiazepine withdrawal110 though this is by no means conclusive.111 There is also data demonstrating that valerian extract may help with benzodiazepine withdrawal,112 but there are equivocal studies that raise concerns about the overall efficacy of valerian extract as an effective sleep treatment.113

Substance abuse (e.g., alcohol, cannabis, and cocaine). Chronic stress is a well-recognized risk factor in the use of substances and addiction vulnerability.125 The etiology is very complex, but early life stress, adverse childhood experiences, and accumulated adversities alter allostasis and associated mechanisms, and are believed to play a significant role in the genesis of addiction. The effects of excessive and repeated substance use result in changes mediated by central catecholamines, particularly norepinephrine and dopamine, both being key players in modulating motivational pathways within the brain. Chronic stress and abuse of substances operate in a feedforward manner to activate the mesolimbic system and beget feelings of reward. This also impairs prefrontal brain circuits, disinhibits executive functioning, activates the amygdala and other brain regions, and causes problems with impulse control, compulsive behaviors, and delaying gratification.

Given this reality, I do not believe it is possible for patients to manage chronic stress and be emotionally regulated if they choose to continue abusing substances. Though harm reduction is a viable approach to managing substance abuse,126 I have not had many patients improve their ability to manage chronic stress (and all the accompanying problems) with continued but reduced substance use. The goal should be to eliminate substance use so patients can learn to live and manage their complex lives without feeling the need to consistently alter their mental state through the compulsive use of substances.

Psychotherapy and/or Social Support to Lessen the Impacts of Chronic Stress

Promoting or recommending psychotherapy is another important treatment that reduces the impact of chronic stress and has therapeutic effects that promote positive brain changes. As Nobel laureate, Dr. Eric R. Kandel, MD, noted in his seminal paper “Psychotherapy and the Single Synapse”:

When [capitalization added] I speak with someone and he or she listens to me, we not only make eye contact and voice contact but the action of the neural machinery in his or her brain, and vice versa. Indeed, I would argue that it is only insofar as our words produce changes in each other’s brains that psychotherapeutic interventions produce changes in patients’ minds. From this perspective, the biologic and psychologic approaches are joined (p.1037).127.

Psychotherapy has been articulated as an epigenetic drug by inducing “changes in brain circuits that can enhance the efficiency of information processing in malfunctioning neurons to improve symptoms in psychiatric disorders, just like drugs” (p.249).9 Published studies have shown, for example, that cognitive behavioral therapy for phobias decreases activity in the limbic and paralimbic areas.128 In depression, psychotherapy was shown to increase and decrease prefrontal metabolism.129 The effects of psychotherapy implicate more top down effects compared to psychiatric medication that produce more bottom-up effects.

A systematic review showed an increase in BDNF levels among depressed patients given treatment with psychotherapy and psychiatric medication.130 The same systematic review also demonstrated a rise in BDNF levels among patients with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) that were given both psychotherapy and physical activity, and a rise in BDNF levels among psychotherapy responders diagnosed with bulimia, borderline, and insomnia.130 A study evaluated the effects on the brain after 15 months of long-term psychodynamic psychotherapy.131 Compared to the control patients, the patients that received long-term psychotherapy showed marked reductions in depressive symptoms, and more activity in the medial prefrontal cortex (PFC). The latter therapeutic effect is important to note since this particular area of the PFC is associated with voluntary emotional regulation.131 Based on the data presented above, psychotherapy has established therapeutic effects that alter brain areas implicated in emotional regulation.

In terms of social support, it would seem reasonable to conclude that similar therapeutic changes would result when people are more socially engaged in meaningful ways. One such example is that of the Experience Corps©–a high-intensity program that combines education, physical activity, and social engagement (as well as other factors not easily quantifiable like meaning and purpose in life)—that trains elderly volunteers to be teachers’ assistants for younger children in neighborhood schools focusing on reading achievement, library support, and classroom behavior.132,133 Participation in the program resulted in improvements in both physical and mental health, but also improved executive functioning in the PFC among the elderly volunteers having an elevated risk for cognitive impairment.

The brain also expects social relationships to happen, as described in an extensive review paper by Holt-Lunstad on why social relationships are important.134 A brief section of the review discussed social baseline theory, which posits that the brain needs to have social relationships that include common goals, interdependence, and attention. In fact, when this expectation is not met, the brain will respond as though there are scarce resources, resulting in increased cognitive and physiological effort, often accompanied by acute and chronic distress. All of this presupposes that the brain has been designed for social relationships as its normal state of being. So when socialization has been limited for a variety of reasons, such as social withdrawal from being depressed or alienation due to neighborhood bullying, the individual suffers both emotionally and neurologically from wounds emanating from the outside in, and from the inside out. It is imperative then that the practicing clinician encourage social integration—for example, weekly recreational sports, book clubs, communal organic gardening—as a central goal when helping all patients to assuage the AL and/or AO from being chronically stressed.

An interesting and more widespread example of fostering social integration (as noted by Holt-Lunstad134) includes the Blue Zones Project (https://www.bluezonesproject.com/), which supports communities by promoting the same principles as described in the book (i.e., The Blue Zones Solution by Dan Buettner). Essentially, the Blue Zones Project advocates for nine factors described in the Blue Zones Solution with the aim to “transform environments to drive physical, mental, social, and professional well-being.” Three of the nine factors are social ones (i.e., family first, right tribe, and belong). Multiple cities across the United States are currently engaged in this project.