Dr. Marianne Marchese

Introduction

Environmental chemicals can alter the immune response and function and increase immune-mediated diseases, such as asthma, allergies, type 1 diabetes, chronic illness, fibromyalgia, and rheumatoid arthritis. The pro-inflammatory immune response induced by exposure to some toxicants contributes to immune dysfunction and is a common factor in many autoimmune diseases. The immune system is composed of multiple organs and cells and an appropriate immune response involves the interaction of multiple cell types, immunoglobulin, and cytokines. These responses are altered by exposure to certain chemicals and/or toxicants.1

The Basics

The way an individual comes into contact with a toxic substance is called the route of exposure and is important in determining the level of toxicity. Different cells and organs often are affected by different routes of exposure. Some chemicals may be highly toxic by one route of exposure but not by others. Two major reasons are differences in absorption and distribution within the body. For example, ingested chemicals, when absorbed from the intestine, distribute first to the liver and may be immediately detoxified. Inhaled toxicants enter the general blood circulation and can distribute throughout the body prior to being detoxified by the liver. Sometimes a person’s genetic make-up determines the effects of chemical exposure on the immune system; this is called epigenetics and is always a factor in determining toxicity. Regardless, it is clear that toxicant exposure does affect the immune system as seen by changes in immune biomarkers and in the development of immune-mediated conditions.

As an example of changes in immune biomarkers induced by chemical exposure, when people with asthma inhale pesticides they not only experience wheezing and inflammation but there are alterations in blood intracellular IFN-γ and IL-4 in T-helper cells. Another example involves high-dose occupational exposure to pesticides, which creates decreased B-lymphocytes, higher serum IgE, and low levels of albumin and serum protein. Lastly, it has been shown that persons with COPD and chronic bronchitis who are exposed to pesticides, dust, gases, fumes, and solvents do worse on pulmonary function tests with lower level of forced expiratory volume and forced vital capacity.2,3,4

Toxicants That Affect the Immune System

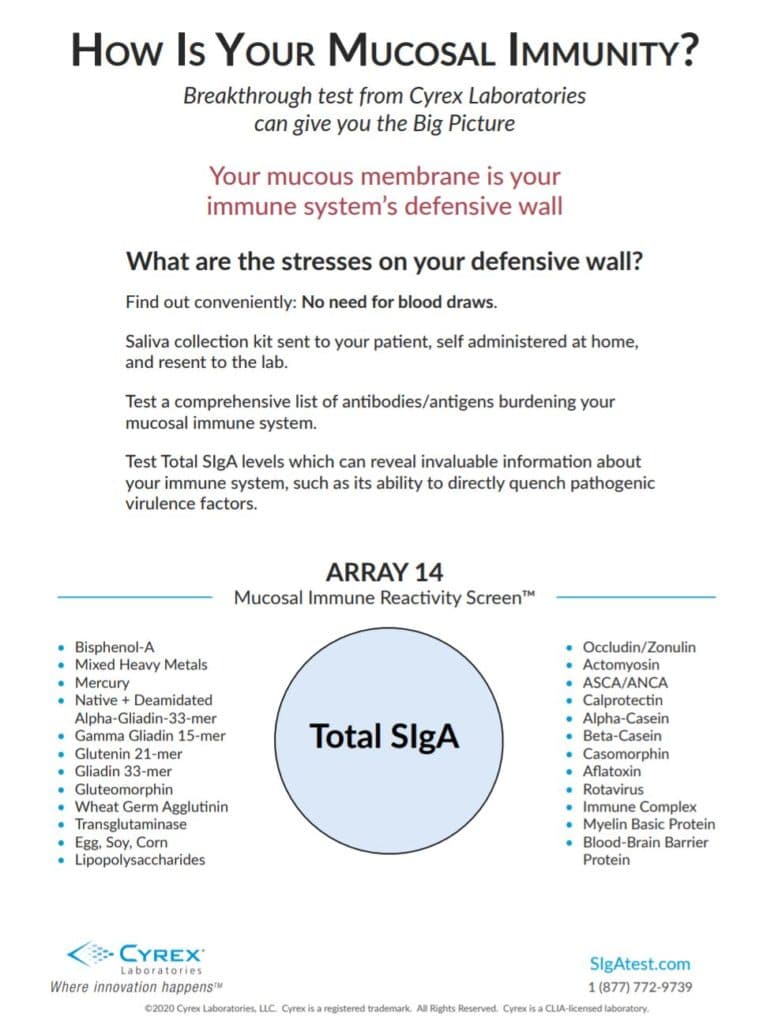

Exposure to mercury, bisphenol-A, and dioxin increases anti-nuclear antibody (ANA), reduces B-cells and T-helper cells, creates mitochondrial damage, depletes glutathione in immune cells, and creates oxidative stress and hypermethylation of leukocytes. These toxicants also trigger conditions such as multiple sclerosis, asthma, allergies, thyroid, lupus, autoimmune hepatitis, scleroderma, and low lymphocyte subsets.5 These toxicants are not uncommon nor are these conditions. People are exposed to methylmercury from eating fish, mercuric acid from skin lightening cream, and mercury vapor from standard dental fillings. Bisphenol-A is present in canned food, paper receipts, hard plastic beverage bottles, and more. Small amounts of dioxin are in food such as meat and dairy, which is the main source of exposure.

Metals such as mercury, cadmium, lead, arsenic from food, water, air and products increase serum immunoglobulin levels and antibody responses to T cell-dependent and T cell-independent antigens and worsening of autoimmune disease. They create increased production of the proinflammatory cytokines, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), IL-1β and IL-6, and production of reactive oxygen intermediates and increased eosinophil degranulation.6 Pesticide exposure in low doses from food can trigger lupus and Hashimoto’s disease.6 Bisphenol-A is also linked to lupus and worsening of other autoimmune conditions.6

These toxicants that alter the immune system are common and exposure is widespread. A person’s genetic make-up can determine how well they process and eliminate these chemicals. Gene and environmental interactions contribute to disease etiology. Because the immune system is immature during development, it’s believed that adult-onset autoimmunity may originate when the immune system is sensitive to exposure such as in-utero. Toxicants impart epigenetic changes (e.g., DNA methylation) that may alter immune function and promote autoreactivity.5

Evaluation of a patient with an altered immune system, chronic illness, or autoimmune condition should include an in-depth environmental exposure history along with general medical history. Laboratory testing may include not only immune and inflammatory markers but also testing for toxicants. Numerous labs now include testing for metals, solvents, pesticides, BPA, parabens, and phthalates. Based on the patients’ symptoms, disease condition, medical and environmental exposure history, and toxicant testing, the treatment may include an environmental medicine approach. Education on avoidance of immune-disrupting compounds is the key to prevention and treatment.