Deborah, and their beautiful grandbabies.

Coping with the Covid-19 Virus

I spend most of my week living and working within miles of the epicenter of the Covid-19 virus outbreak in the US. This is in Kirkland, WA—yes, the same town where Costco was founded. Also, near the nursing home with the outbreak is the Redmond Microsoft campus. And just across Lake Washington sits Seattle’s Amazon campus. While Covid-19 has not been labelled a pandemic (yet), it is now officially endemic in our community. What that means is that in this first week of March schools have been closed and white-collar workers are being ordered to work from home. (I suppose working from home with pay is a benefit). We had a day where people lined up at 8:00 in the morning to rush into Costco to purchase toilet paper—the thinking was there would be no more shipments of it from China. Rush hour traffic disappeared going in and out of Seattle on a weekday. (Of course, some parents are now being really stressed trying to get their kids to study and stay off the screen.) Meanwhile the death rate from the virus continues to eke up on a daily basis (even though it is fewer than those who die daily worldwide from snake bite). There are those clamoring to impose a more community-wide quarantine; there are those who are despairing, worrying about what they will do when they begin to get cold and flu symptoms. People want to get tested, but there are not enough test kits; people don’t want to get tested so they can charade that they are not ill and don’t have the virus. In Seattle we are preparing to be human guinea pigs for the Covid-19 vaccine testing when it has passed muster with animals. In the meantime, if you have a loved one in that Kirkland nursing home, don’t expect to get visitation anytime soon. Local authorities are holding their breath fearing a sudden spike of critically ill patients that would overwhelm regional critical care units. Staving off that fear is going to take more than just staying home and washing one’s hands.

In the first week of March the Shanghai Clinical Treatment Expert Group published a “Comprehensive Treatment and Management of Corona Virus 2019: Expert Consensus Statement.” (Chin J Infect Dis, 2020, http://rs79.vrx.palo-alto.ca.us/opinions/ideas/pharma/ortho/08_Cov/2019-NCoV/timeline/mar/01/protocol/)

The protocol, authored by infectious disease and critical care physicians, in China offers conventional and traditional medicine treatment interventions for non-severe and critically ill patients. For antiviral treatment it is advised to use oral hydroxychloroquine or nebulized interferon gamma. High-dose intravenous ascorbic acid and heparin anti-coagulation is suggested. Fluid and electrolyte replacement are obligatory to prevent organ failure. To reduce lung interstitial inflammation, broad spectrum protease inhibitors are advised. Parenteral nutrition is recommended through nasal feeding. Oxygen by nasal catheter is needed; mechanical ventilation is obligatory with severe respiratory distress and shock. Corticosteroids should be administered cautiously; cultures should be done to determine need for co-infection treatment with antibiotics and/or antifungals. Given the breadth of therapies, monitoring for nosocomial infection and iatrogenic problems is obligatory. Traditional Chinese medicine with herbals is also advised.

When We Do Harm Prescribing Supplements

One of the truisms that we all believe is that unlike pharmaceuticals supplements pose little risk to the patient and may offer great benefit. Given that they are composed primarily of vitamins, minerals, amino acids, digestive enzymes, and botanicals, there is little likelihood of harm from their consumption. Of course, some supplements are adulterated with drugs and chemicals that do have the same risk profile as pharmaceuticals. Equally insidious are herbs that have been contaminated with toxic metals and harmful chemicals. A protocol of extensive supplementation, requiring the use of 10, 20, 30 or more individual supplements, increases the risk that there may be adulteration with drugs or chemicals and interaction with prescribed medications. It is very difficult to assess such risk given the proprietary nature of most supplement manufacturing and the rarity of disclosure of quality control testing. Consumers and doctors accept on blind faith that the label accurately specifies the supplement’s contents and assume no adulteration. Hence, it is very difficult to determine if a patient’s condition has been negatively impacted by the use of supplementation.

On a Fox television series, “The Resident,” an episode featured a leading hospital physician promoting a supplement touting a unique formulation that offered major health prevention benefits. As patients began to use the supplement, there appeared a bizarre incidence of organophosphate poisoning among a few of its users. The TV drama focused on the panicked concern by the surgeon promoting the supplement and a possible connection between the supplement use and the spate of pesticide poisoning. Worried about the serious fallout that would ensue if such a relationship could be confirmed, the company executives were being asked to pull the supplement from the marketplace. At the last minute a physician asked to review the hospital cases of organophosphate poisoning and noted how individuals who had been successfully treated relapsed after putting on their street clothes immediately on being discharged. The astute resident observed that clothing purchased from a mail order house by these patients was the culprit as the garments were contaminated with the pesticide. Consequently, the poisoning was the result of direct skin contact not by consuming an adulterated food supplement.

Television drama oversimplifies medical etiologies. However, the possibility that patients may be incurring harm using supplements is an ever-present risk—one that we need to always consider as our patient’s health changes.

Can We Really Survive to 125?

Our cover story in May featuring Suzanne Somers focuses on anti-aging—how one can extend one’s life not just in chronological years but while manifesting vibrant health physically and mentally. Some in the life extension field have predicted that not only will this be a reasonable goal in the near future but we should anticipate life expectancies of 125 or longer. Of course, once one has begun to incur major illness and degenerative disease, such longevity begins to seem less likely if not unlikely. Nevertheless, Somers would argue having personally survived breast cancer that one can turn one’s life around and embrace a life extension plan that will indeed manifest in good health and vitality. Fortunately for Somers, her cancer never progressed to metastatic disease; indeed, she would also opine that we need to incorporate a vigorous health-building plan before such serious degeneration develops. It is courageous to use one’s own health as an example, a model, for others to emulate and serve as a guidepost to limitless vim and vigor. Yet, Suzanne is willing to stick her neck out and offer herself as such a paragon—and she has written 27 books over her life, interviewing doctors and researchers who confer their expertise on longevity.

Still how does one put their head around the idea of living to 125 when no one lives to that age? Well, yes, no one has lived to that age but there is a single individual, a French woman, Jeanne Calment who lived from 1875 to 1997, documented in the Guinness Book of Records as living to age 122. The Feb. 17/24, 2020 issue of The New Yorker, ran an extended article by Lauren Collins on the evidence that Calment lived as long as she claimed; the article, “Living Proof,” examines reports that have appeared recently attacking the veracity of Calment’s long life. It is a fascinating story well worth reading. Undoubtedly, her hormone levels were definitely higher than most women when she was age 90—she would be able to conduct herself physically, socially, and mentally like a woman 40 years younger. Of course, Calment never used supplemental hormone therapies—she just behaved like a woman who did. Indeed, Calment did not use any life-extending treatments and did not restrict her diet nor did she avoid alcohol. But she was a “tough cookie.” “She maintained a rigid schedule, rising at 6:45 a.m., said her prayers, performed calisthenics, and listened to classical music on her Walkman…She proudly told Paris Match that her breasts remained as firm as ‘two little apples’…Behind her back, the nurses called her la commandante. She only quit smoking at 117, never giving up having a nightly glass of port.”

What are we to make of Calment’s use of tobacco and alcohol? Her physical exercise? Her toughness and demanding nature? Are these the keys to longevity?

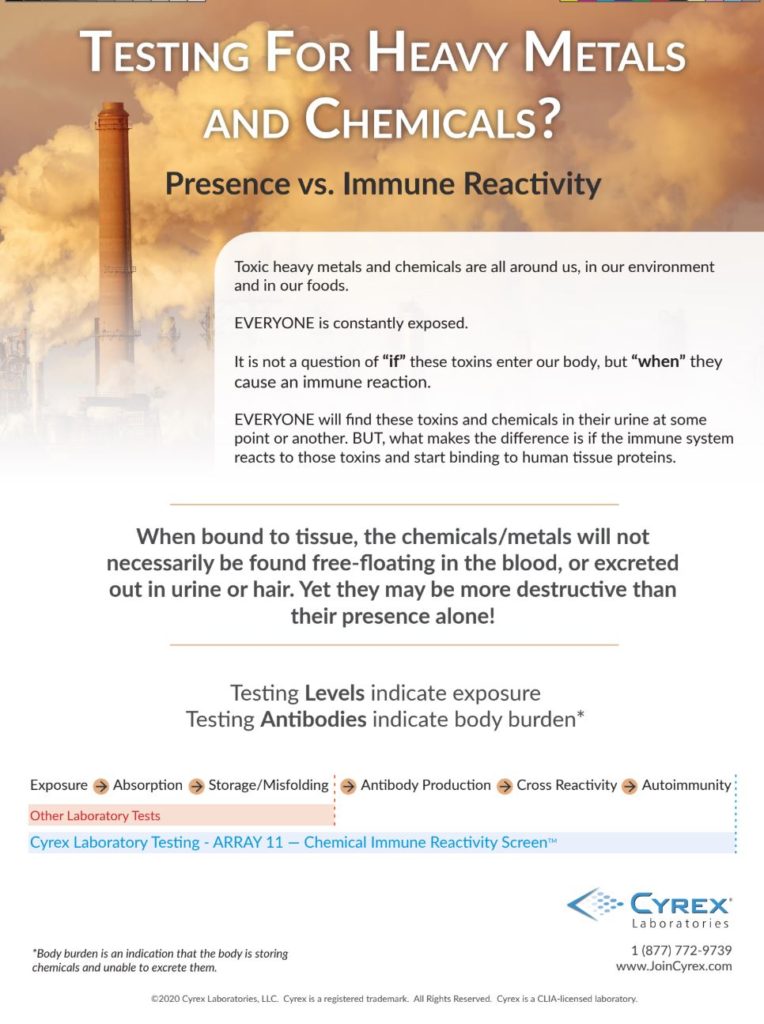

Suzanne Somers: A New Way to Age

For sure, Somers would not tout tobacco or alcohol. Her new book, A New Way to Age: The Most Cutting-Edge Advances in Antiaging, asks us to consider adapting a health plan that is more aggressive than simply eating well, exercising, using some supplements, sleeping adequately, and reducing stress. Such a prudent diet, being active, and having good sleep hygiene will certainly lead us to a good life through our 80s but not longer and will not necessarily fend off terrible degenerative conditions or cancer. The doctors Somers interviews would have us use supplemental bio-identical hormone therapy, even if we are not symptomatic, if our hormone levels are not optimal. Detoxification of toxic metals and chemicals is critical for a longevity plan—not only do we need to eliminate toxins that we consume in our beverages and food but also in our cosmetics and household cleaning agents. An active program to remove these toxins, using the Hubbard protocol with infrared sauna treatment, is necessary. Somers advocates strongly for the use of enhanced external counterpulsation (EECP) as a technique to use in patients who suffer from heart disease.

As expected Somers also advocates for the use of the “latest anti-aging” supports promoted by life-extension advocates. Bill Faloon, founder of Life Extension Foundation, champions the use of NAD+ (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide) supplementation that can be administered intravenously, topically, and as oral supplementation; NAD+ is reported to repair DNA breaks, a common part of the aging process. Another genetic issue, chromosomal shortening referred to as telomere shortening, is also thought to contribute to the aging process; certain supplementation has been established to reverse the shortening of telomeres. No discussion of anti-aging medicine would be complete without examination of stem cell therapy. The orthopedic use of stem cell therapy in combination with platelet rich plasma (PRP) has nearly become mainstream in clinics around the US as treatment for degenerative arthritis and related conditions. Certainly, it would be reasonable to consider such treatment before agreeing to surgical replacement of joints.

Suzanne Somers provides us with her view of “a new way to age” in this issue. The book also serves as a resource for the doctors working in life extension medicine. A good read for the waiting room.

I didn’t get a chance to talk about this issue’s theme—cardiovascular health—and the doctors who penned their thoughts on maximizing one’s heart status. Please spend some time taking a gander at Fraser Smith, ND’s examination of cardiovascular inflammation, Joel Kahn, MD’s approach to treating heart failure, and Jeremy Mikolai, ND’s use of carnitine in circulatory disorders. Don’t forget Jacob Schor, ND’s curmudgeonly comments regarding eggs and cholesterol.