by Kurt Beil, ND, LAc, MPH

Spending time in nature is part of the timeless human experience and something most people appreciate and incorporate into their lives. Recently, empirical research has identified how beneficial this ancient experience is to our health and well-being. Many different nature-based therapies (NBT)* have demonstrated positive effects in a variety of health areas, ranging from mental health conditions like depression, anxiety, and concentration to positive alterations in biomarkers of physical health such as cortisol, blood pressure and heart rate variability.1–3 These exciting findings are being applied across many different areas of health exploration.

One area of interest is the use of NBT for treating and supporting patients with cancer, one of the most common and most impactful diseases in healthcare. Breast cancer, in particular, is of interest as it is the most common form of cancer in women and second highest cause of female cancer mortality.4 NBT is an especially appealing approach to assist women with breast cancer because it simultaneously addresses multiple aspects of health in a supportive, low-cost, low-impact way.5-6

*Note: No standardization or distinct demarcation of terminology has been identified to this author’s knowledge for use in this new area of clinical techniques. Use of terms such as nature-based therapy, nature therapy, forest therapy, natural restorative experiences, ecotherapy, ecological medicine, environmental therapy, nature cure, biophilic medicine/therapy, etc… are often used interchangeably at the current time. The use of “nature-based therapy” in this article is not meant to connote preference for this term over any other, conceptually or otherwise.

Forest Therapy

The currently most talked about form of NBT is forest bathing (originated in Japan as shinrin-yoku) which has been written about in many academic and public media sources.7,8 This full-sensory immersion in the forest environment has years of research demonstrating its physical and mental health benefits. Some studies of healthy female participants have investigated how forest bathing (aka forest therapy or FT) can provide women with psychological improvements in mood, anxiety, and quality of life (QOL), as well as physiological improvements in salivary cortisol, heart rate, heart rate variability (HRV), and lung capacity in exposures ranging from only 15 minutes to three full days.9–12 And a few studies have provided evidence of FT’s potential for specifically benefitting women with breast cancer.

Possibly the most famous FT study, published less than a decade ago, is one of these. It involved healthy participants and the impact that just a few hours in a forest environment, but not a “control” urban one, had on increases in their serum natural killer (NK) cells. These immune system cells are well-known for their ability to identify and reduce the size of cancerous tumors.13 Elevated blood concentration of NK cells and their “cytotoxic arsenal” of perforin and granzyme enzymes14 remained for more than 30 days after a single forest exposure, leading to much interest in FT as a complementary addition to cancer treatment and prevention.

Other studies have followed up these findings. In a Korean study published in 2015, eleven women with diagnosed stage I-III breast cancer participated in a two-week forest therapy immersion program outside of Seoul.15 These women lived in a forest cabin during this experience and participated in daily two-hour forest walks every morning. Their afternoons were spent with free-time activities and group sessions discussing their experience of breast cancer treatments as well as other personal topics. Meals were standardized according to Korean nutritional health guidelines. Blood samples were collected from these women at the beginning (Day 1) and end (Day 14) of the forest therapy experience, as well as one week after returning home to regular life (Day 21), to measure concentrations of NK cells, perforin, and granzyme B.

For the women in this study, the results were substantial. Levels of NK cells increased 39% during the two-week FT experience and were still elevated 13% above baseline on Day 21, one week after returning home. Perhaps more impressively, NK cells’ arsenal of cancer-fighting enzymes increased significantly throughout the study and continued increasing after the completion of the FT. The serum concentrations of perforin and granzyme B rose 59% and 155% (respectively) from Day 1 to Day 14 and continued a very notable rise to levels 114% and 359% (respectively) above baseline when measured after participants had returned home for a week on Day 21.

These findings show an intensive up-regulation of the tumor-fighting capacity of the immune system and suggest substantial benefits of FT to support women coping with breast cancer. These results should be taken with caution, as this was a preliminary feasibility pilot study with only 11 participants that included no control group. However, if these results can be replicated, this has large implications for the inclusion of FT as an adjunctive therapy for breast cancer and many other cancers and other health conditions benefitted by NK cell activity.

Supportive Well-Being and QoL

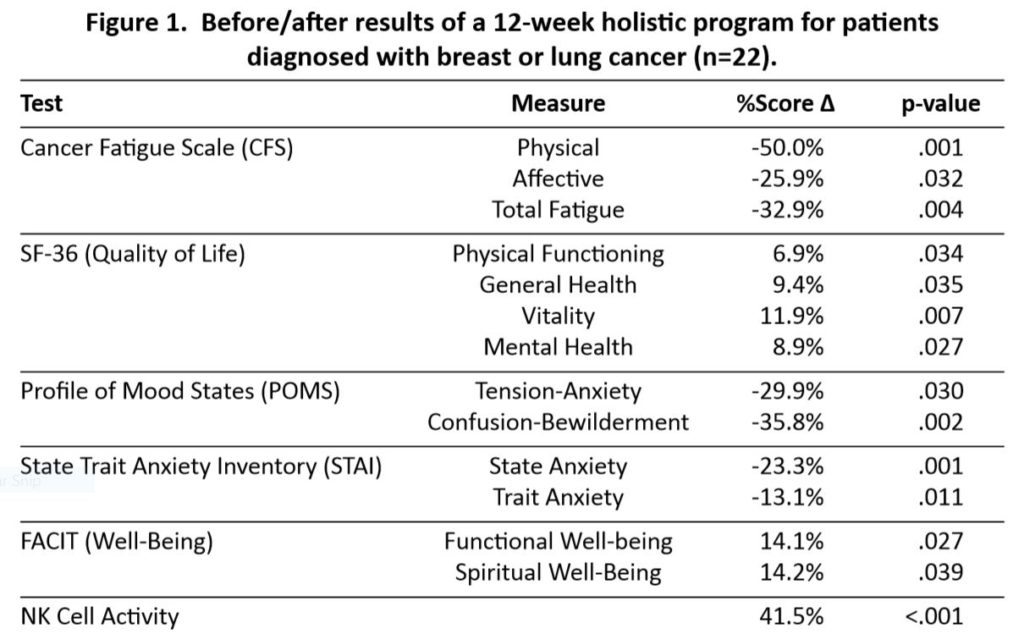

Of course, increasing NK cell activity is just one aspect of addressing cancer. More broadly-reaching studies have investigated FT and other NBTs’ ability to support the whole person. One such study published in 2013 had 22 cancer-diagnosed individuals (Note: Only 18 of the participants were female and diagnoses were a mix of breast and lung cancer) participate in twelve weekly non-residential six-hour sessions of FT as well as horticulture therapy (gardening), yoga, and group counselling.16 NK cell activity was assessed before and after the twelve week session, as were extensive subjective measures of physical and mental well-being. At the end of the twelve-week session, all participants had increased NK cell activity (41.5% above baseline). In addition, pre-post subjective measures showed substantial benefits in areas of cancer-related fatigue, QoL, mood, anxiety, and well-being, all p<0.05 (see Fig 1, below). All participants reported highly positive feedback and indicated they would like to see this type of experience made more commonly available as part of routine cancer care.

These results are valuable because they remind us of the holistic, patient-centered reality of cancer. Fatigue, mood, anxiety, and sense of well-being are all issues that significantly impact the quality of life of individuals experiencing cancer and can be very difficult to address through conventional medical care alone. NBTs such as the ones in this study improve the life and reduce the difficulties of the person with cancer, more than just addressing the tumor.

Focus, Attention, Mental Health, and Stress

One of the most common sequelae of a cancer diagnosis is impairment of cognitive function, particularly mental acuity and the ability to focus attention. In addition to physical symptoms such as pain, other issues like navigating doctor visits, maintaining personal and professional responsibilities, avoiding social stigma, and fear of impending mortality can greatly impair attention. This often leads to distractibility, poor concentration and memory, and increased impatience. And these are all before considering the damaging cognitive effects of chemotherapy recognized as “chemo brain.”17 These all degrade quality of life for women diagnosed with breast cancer, beyond the challenges of the physical disease itself.

Fortunately, exposure to Nature helps with this too! Everyone has experienced the relaxing peace of mind that comes from taking a walk in the woods or stroll through a park. As noted by famed 19th century landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, “The enjoyment of [natural] scenery employs the mind without fatigue and yet exercises it; tranquilizes it and yet enlivens it; and thus, through the influence of the mind over the body gives the effect of refreshing rest and reinvigoration to the whole system”18

One study that effectively demonstrates this refreshing rest was conducted in Michigan with 157 women newly diagnosed with breast cancer.19 These women were participated in a series of home-based natural restorative experiences (NREs) for a minimum of 120 minutes per week for an average of 36 days, from the time just after their diagnosis to a time after surgery but before beginning adjuvant therapy (e.g. chemotherapy, radiation). NRE were defined as any experience in nature fulfilling four criteria as originally defined by University of Michigan professor Stephen Kaplan’s classic Attention Restoration Theory20:

- Fascination: The NRE should easily capture one’s interest.

- Being Away: The NRE should mentally and/or physically remove one from typical daily routines, concerns, and/or locations.

- Extent: The NRE should not be boring or become tedious.

- Compatibility: The NRE should be personally enjoyable and/or pleasant.

Options to experience different NRE were provided and included but were not limited to (in participants’ own words): “tak[ing] care of my garden,” “walk[ing] along the river,” ““watch[ing] a beautiful sunrise,” and “spend[ing] an hour with my plants.” Multiple regression analysis demonstrated that women who engaged in NRE had significant improvements in standard measures of memory, focus, and concentration compared to no changes in the wait-listed control group (b= -0.872 (0.345), β= -0.158, p<0.01).

These benefits can be considered as part of NBT’s ability to ease mental fatigue and reduce the significant impact of stress that a diagnosis of cancer can bring. Such effects are well-recognized in the cancer community, such that the field of “psycho-oncology” has been established to focus specifically on reducing the detrimental mental burden of cancer, including impacts on mood, concentration, and QoL.21–23

Various other NBT may be useful in addressing these issues in ways similar to other healthy and clinically affected populations, as shown by multiple reviews and meta-analyses.3,24,25 The underlying effects are based on humans’ inherent affinity and evolutionarily derived “biophilia” to respond positively to restorative natural settings.26,27 This applies to both the psychological and physiological components of stress that influence mental and physical health.2,28 Substantial evidence supports the concept that nature provides restorative, health-promoting, “salutogenic” experiences for all people,29 and NBTs can be especially effective in providing this type of support to women with breast cancer.

Qualitative Nature Experience

Navigating life with breast cancer is of course more than just a collection of lab values and subjective quality of life scores. It is a daily experience that is challenging, frustrating, difficult, nonsensical, heartbreaking, and so many other mixed emotions. To address each of these, spending time in the “therapeutic landscapes” of the natural world can be incredibly valuable and supportive during this process. Nature is a source of inspiration, a place of refuge, an opportunity for distraction, and so much more. Some of the descriptive research on these topics has explored the common themes of nature exposure for women with cancer,30 and found the most common reported benefit was the ability of nature to provide women with a sense of personal connection to something of value. For some women this was the land and natural features themselves, while in others it was cherished memories of time spent with loved ones or internal reflections on forgotten parts of the self. Other common ways nature has supported women through the challenges of breast cancer are as a place of emotional safety and strength during treatment, or as a place of refuge and escape from mental and physical difficulties.31,32 Additionally, there are many symbolic and aesthetic aspects of being in nature that provide insight and joy to many women, in ways that transcend cultures.33 Other more extensive work from a feminist or eco-feminist lens are beyond this author’s expertise to comment on and are referenced here for the benefit of readers that would like to explore these valuable topics further.34,35

Public Health Evidence

All of the benefits of NBT mentioned above exist for anyone spending time in nature, whether they are participants in a scientific study or not. As evidence of this, there are some large-scale epidemiological investigations that show proximity to nature may be preventive or protective against breast cancer. In one study in Spain, women (n=2,748) were found to have a 35% lower (OR 0.65, 95%CI 0.49–0.86) risk of having breast cancer if they lived in areas of high vs. low residential green space, defined as a forest, park, public garden, etc…within 300 meters of their homes.5 These findings were significant after adjusting for other potential factors such as socio-economic status, menopausal status, number of children, family history of breast cancer, population density, level of physical activity, and amount of air pollution. These results are similar to another large-scale study in Japan using the entire National Health System data set of ~126 million people, which revealed a highly significant inverse correlation between residential proximity to a forest and a woman’s risk of having diagnosed breast cancer (r=-0.530, p<0.0001).6 Clearly, there are many benefits of being close to nature.

Conclusion

People have a timeless connection with the natural world as a source of sanctuary and solace from physical and mental ills and stresses. The challenges presented by breast cancer are significant and frequently difficult to manage, especially in the modern world. This article has detailed how the scientific method provides supportive evidence of the benefit of nature-based experiences (called various names such as nature-based therapy, forest therapy, horticulture therapy, natural restorative experiences, and more) to make these challenges easier and provide healing to mind and body. Many more years and research studies will be needed to establish clinical “best practices” of NBT regarding type of exposure and “dose/frequency prescriptions” for various conditions and personal individualized preferences. Long-term investigations will be needed to evaluate whether regularly visiting a forest affects breast tumor size, or exactly how much improvement in subjective well-being can be anticipated from these visits. However, we know that these ancient experiences of connection with our natural surroundings are well-tolerated, low-cost, low-risk interventions that can be incorporated into holistic breast cancer treatment programs to benefit women’s experiences and lives.

References

1. Mygind L, et al. Immersive nature-experiences as health promotion interventions for healthy, vulnerable, and sick populations? A systematic review and appraisal of controlled studies. Front Psychol. 2019;10(APR).

2. Antonelli M, Barbieri G, Donelli D. Effects of forest bathing (shinrin-yoku) on levels of cortisol as a stress biomarker: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Biometeorol. April 2019:1-18.

3. Kondo MC, Jacoby SF, South EC. Does spending time outdoors reduce stress? A review of real-time stress response to outdoor environments. Health Place. 2018;51:136-150.

4. CDC. Breast Cancer Statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/breast/statistics/index.htm. Published 2019. Accessed December 14, 2019.

5. O’Callaghan-Gordo C, et al. Residential proximity to green spaces and breast cancer risk: The multicase-control study in Spain (MCC-Spain). Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2018;221(8):1097-1106.

6. Li Q, Kobayashi M, Kawada T. Relationships Between Percentage of Forest Coverage and Standardized Mortality Ratios (SMR) of Cancers in all Prefectures in Japan. Open Public Health J. 2008;1:1-7.

7. Hansen MM, Jones R, Tocchini K. Shinrin-yoku (Forest bathing) and nature therapy: A state-of-the-art review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(8).

8. Beil K. Forest Bathing: Immersion in the Healing Power of Nature. Townsend Lett. 2018;(July #420).

9. Song C, et al. Effects of Walking in a Forest on Young Women. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(2).

10. Yu YM, et al. Effects of forest therapy camp on quality of life and stress in postmenopausal women. Forest Sci Technol. 2016;12(3):125-129.

11. Lanki T, et al. Acute effects of visits to urban green environments on cardiovascular physiology in women: A field experiment. Environ Res. 2017;159(June):176-185.

12. Lee JY, Lee DC. Cardiac and pulmonary benefits of forest walking versus city walking in elderly women: A randomised, controlled, open-label trial. Eur J Integr Med. 2014;6(1):5-11.

13. Miller JS, Lanier LL. Natural Killer Cells in Cancer Immunotherapy. Annu Rev Cancer Biol. 2019;3(1):77-103.

14. Backes CS, et al. Natural killer cells induce distinct modes of cancer cell death: Discrimination, quantification, and modulation of apoptosis, necrosis, and mixed forms. J Biol Chem. 2018;293(42):16348-16363.

15. Kim BJ, et al. Forest adjuvant anti-cancer therapy to enhance natural cytotoxicity in urban women with breast cancer: A preliminary prospective interventional study. Eur J Integr Med. 2015;7(5):474-478.

16. Nakau M, et al. Spiritual Care of Cancer Patients by Integrated Medicine in Urban Green Space: A Pilot Study. EXPLORE. 2013;9(2):87-90.

17. Hermelink K. Chemotherapy and Cognitive Function in Breast Cancer Patients: The So-Called Chemo Brain. JNCI Monogr. 2015;2015(51):67-69.

18. Olmsted FL. Nature , Health & Well-being Health & Environment. 1865.

19. Cimprich B, Ronis DL. An Environmental Intervention to Restore Attention in Women With Newly Diagnosed Breast Cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2003;26(4):284-292.

20. Kaplan S. The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. J Environ Psychol. 1995;15(3):169-182.

21. Holland JC. Psycho-oncology: Overview, obstacles and opportunities. Psychooncology. 2018;27(5):1364-1376.

22. Pérez S, et al. Acute stress trajectories 1 year after a breast cancer diagnosis. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(4):1671-1678.

23. Kang D-H, Park N-J, McArdle T. Cancer-Specific Stress and Mood Disturbance: Implications for Symptom Perception, Quality of Life, and Immune Response in Women Shortly after Diagnosis of Breast Cancer. ISRN Nurs. 2012;2012:1-7.

24. Houlden V, et al. The relationship between greenspace and the mental wellbeing of adults: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2018;13(9).

25. McMahan EA, Estes D. The effect of contact with natural environments on positive and negative affect: A meta-analysis. J Posit Psychol. 2015;9760(December):1-13.

26. Ulrich RS. Natural versus urban scenes: Some psychophysiological effects. Environ Behav. 1981;13(5):523-556.

27. Wilson EO. Biophilia. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1984.

28. Twohig-bennett C, Jones A. The health benefits of the great outdoors: A systematic review and meta-analysis of greenspace exposure and health outcomes. Environ Res. 2018;166(June):628-637.

29. Von Lindern E, Lymeus F, Hartig T. The Restorative Environment: A Complementary Concept for Salutogenesis Studies. In: Mittelmark MB, Sagy S, Eriksson M, et al., eds. The Handbook of Salutogenesis. Springer; 2016:1-461.

30. Blaschke S. The role of nature in cancer patients’ lives: A systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis. BMC Cancer. 2017;17(1):1-13.

31. English J, Wilson K, Keller-Olaman S. Health, healing and recovery: therapeutic landscapes and the everyday lives of breast cancer survivors. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(1):68-78.

32. Pascal J. Space, Place, and Psychosocial Well-Being: Women’s Experience of Breast Cancer at an Environmental Retreat. Illness, Cris Loss. 2010;18(3):201-216.

33. Liamputtong P, Suwankhong D. Therapeutic landscapes and living with breast cancer: The lived experiences of Thai women. Soc Sci Med. 2015;128:263-271.

34. Szumacher E. The feminist approach in the decision-making process for treatment of women with breast cancer. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2006;35(9):655-661.

35. Lynch L. Rapture and the Volcano: A Special Issue on Women and the Natural World. Ecopsychology. 2010;2(3):121-123.

Kurt Beil, ND, LAc, MPH is a naturopathic and Chinese medicine practitioner with practices in Sandy, Oregon, and New York’s lower Hudson Valley region. He is a research investigator at NUNM’s Helfgott Research Institute, where he focused on biomarker and psychometric assessment of the restorative and therapeutic effect of natural environments. Dr. Beil is also an editor of the Natural Medicine Journal, the official journal of the American Association of Naturopathic Physicians, and writes a regular column reviewing papers on the healing power of contact with nature. He holds a master’s degree in public health focused on the benefits of green space as a sustainable public health promotion tool, and speaks, writes, and peer-reviews regularly about these topics. Dr. Beil also maintains a regular public blog and Facebook group (“Naturopaths for Nature”) on these topics, and gets out to walk his talk in nature as often as possible. He can be reached at drkurt@earthlink.net or www.drkurtbeil.com.