by Jonathan E. Prousky, ND, MSc

THIRD PLACE WINNER!

Best of Naturopathic Medicine 2013

Abstract: The author’s private clinical practice focuses on the evaluation and treatment of mental disorders. One of the most common requests from patients involves their desire to reduce or discontinue one or more psychotropic medications. It is entirely appropriate for patients to request this. Their psychotropic drugs might be doing more harm than good by creating objectionable side effects, which may limit rather than enhance their quality of life. Issues related to pharmacological dependence and discontinuation reactions are described. Since there is a scarcity of clinical research pertaining to tapering patients off psychotropic drugs, there are no clearly defined standards to inform clinicians about the most appropriate method of tapering. The author recommends an integrative approach (when possible) involving communication between the prescribing clinician (i.e., the patient’s psychiatrist or family doctor) and the clinician proposing the tapering plan. The tapering plan should involve one drug at a time and reduce the drug with the longest elimination half-life first. Overall, the tapering plan needs to be very slow and gradual in order to reduce the potential for relapse. Diet, lifestyle modifications, and specific natural health products can significantly improve a patient’s chances of successfully tapering psychotropic drugs. Several examples of tapering schedules are described. Each plan was individualized to suit the patient’s needs, and support mental stability. This article should assist and empower clinicians to develop effective tapering strategies on behalf of willing and mentally competent patients.

Introduction

For over a decade I have focused the majority of my clinical practice on the evaluation and treatment of mental disorders. One of the most common requests that I receive from patients stems from their desire to reduce or discontinue psychotropic medications. It is entirely appropriate for patients to request this. Their psychotropic drugs might be doing more harm than good by creating many objectionable side effects, which may limit rather than enhance their quality of life.1 Patients might want to see how they feel and function once their psychotropic drugs are reduced and/or discontinued. They might also wish to be drug free. When this request it made, I usually tell then something along the lines of: “I need to see that you are stable for at least 6 months before there is any consideration of reducing and/or discontinuing your psychotropic medication. By ‘stability,’ I mean getting along well with family and friends; maintaining some type of regular work or employment, such as school, a volunteer position, or a career; and having no more disabling symptoms of your psychiatric disorder.”

This is usually well received, since most patients prefer to work in a slow, methodical fashion, rather than becoming destabilized should this process be rushed.

Difficulties in Overcoming Pharmacological Dependence

Pharmacological dependence is an expected and biological adaptation of the body becoming long habituated to the presence of psychotropic drugs.2 Since psychotropic drugs can induce unpredictable global reactions when used properly, there are no reliable ways to predict how patients will overcome pharmacological dependence once their psychotropic drugs are tapered and eventually withdrawn.3,4 Every patient’s withdrawal process is unique, as is his or her susceptibility to develop withdrawal side effects.5

One helpful barometer of potential success is the length of time of psychotropic drug use. In one report, patients taking psychotropic drugs for less than 6 months were more successful at tapering off (81%), compared with patients on drugs for more than 5 years (44%), and patients on drugs between 6 months and 5 years (a little over 50%).5

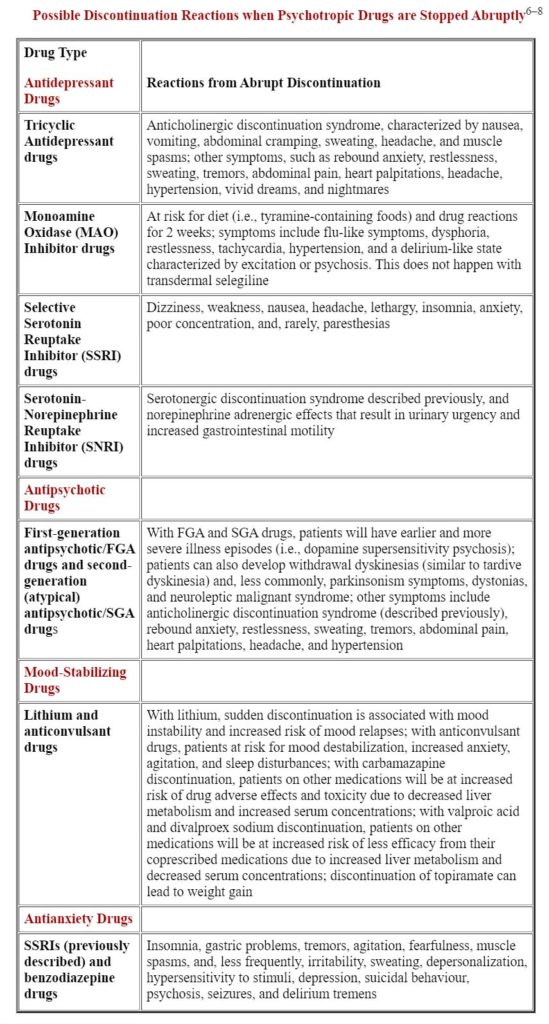

Discontinuation Reactions Following Cessation of Psychotropic Drugs

Some patients do fine and experience little withdrawal, while others have become so habituated to and dependent on their psychotropic drugs that stopping them is paramount to disaster. While no ethical clinician would instruct a patient to abruptly stop taking his/her psychotropic drugs, it is important for clinicians to recognize discontinuation reactions connected with the common classes of psychotropic drugs.

Tapering Patients off their Psychotropic Drugs

When it is appropriate for this to happen, I usually communicate in writing to the patient’s prescribing clinician (i.e., the general/family practitioner or psychiatrist) that our mutual patient is doing well and wants to try discontinuing one of his/her psychotropic drugs. I have made many requests to my patients’ prescribing clinicians (e.g., psychiatrists), particularly about switching from a psychotropic drug with a short elimination half-life to a similar psychotropic drug with a longer elimination half-life prior to tapering.

In the majority of cases, the prescribing clinicians have cooperated with me and agreed to the proposed tapering strategy. However, if the prescribing clinician does not agree to any plan of psychotropic drug tapering, despite the patient’s wishes and noted stability, it is entirely appropriate for the patient and the nonprescribing clinician to proceed with a tapering plan. In such a circumstance, it might be suitable to draft a waiver (i.e., a release) outlining all potential risks and benefits of psychotropic drug tapering and review this with the patient. This waiver would clearly delineate that this is what the patient wants, and that the patient is willing to assume all risks (e.g., destabilization and hospitalization) associated with the tapering process.

Since there is a scarcity of clinical research pertaining to tapering patients off psychotropic drugs, there are no clearly defined standards informing clinicians about the most appropriate method of tapering. Patients are just as likely to succeed in coming off their psychotropic drugs when they have support and endorsement from their prescribing clinicians as when they do not.9 The published data from one organization found that 53% of patients were successful in coming off their psychotropic drugs – even though this was either against their doctors’ advice or occurred without their doctors’ knowledge – compared with 44% who had their doctors’ approval.5

Overall, the tapering plan needs to be very slow and gradual to reduce the potential for relapse.1 The patient should never be made to feel like a failure during this process, since coming off psychotropic drugs is very difficult due to the “physiological and psychological manifestations of the biological effects caused by the withdrawal of a regularly-administered drug.”1 For patients to successfully come off psychotropic drugs they need to: (1) be well prepared and informed about the process; (2) have a positive attitude; (3) keep in mind that they will experience strong emotions throughout tapering and possibly for months after; and (4) receive some type of regular psychological support (e.g., psychotherapy, art therapy, support groups, etc.) during the tapering and perhaps beyond.9,10

A good rule of thumb is for the tapering duration to be for the same length of time of previous psychotropic use.10 For example, if a patient was taking a psychotropic drug for 6 months, the tapering process should last for 6 months. The only exception involves patients who have been on psychotropic drugs for 5 or more years. The tapering process for these patients should be approximately 18 to 24 months.10 However, each patient situation is different, so the time allotment for tapering needs to be individualized to the patient’s needs and to what is possible.

The tapering plan should involve one drug at a time and reduce the drug with the longest elimination half-life first. Psychotropic drugs with longer elimination half-lives (i.e., more than 24 hours) are easier to taper, since their withdrawal reactions tend to be less severe than drugs with shorter elimination half-lives (i.e., less than 24 hours). Psychotropic drugs with short elimination half-lives can produce significant and quick withdrawal reactions. Considerations should be made to switching patients from psychotropic drugs with short elimination half-lives to drugs with longer elimination half-lives prior to tapering, as this will increase the chances of a positive experience and successful outcome. A psychotropic drug such as venlafaxine (which has an elimination half-life of around 5 hours) can cause significant withdrawal and possible destabilization. A psychotropic drug such as fluoxetine, on the other hand, can be used as a substitute for venlafaxine, allowing for a more successful tapering plan, since the elimination half-life of this drug is 4 to 6 days.9

One report suggests that for each unspecified tapering period, there should be a 10% reduction in dose, meaning that the psychotropic drug gets reduced by subsequent 10% reductions until the patient is comfortably off his/her medication.9 Another report suggests that the psychotropic drug is tapered down every 2 weeks, so that after each 2-week tapering period, the dose is further reduced by 10%.10 If a patient, for example, begins the tapering process on a drug that is 400 mg once daily, then the dose to take for 2 weeks would be 360 mg. After two weeks, the dose would be further reduced by another 10% to 320 mg and so on. This process would continue until the psychotropic drug is fully discontinued. If the patient feels that the reduction is too marked or there are troublesome withdrawal reactions such as anxiety and sleep disturbances at any time during the tapering, the patient can remain on the previous tapered dose until he/she feels well enough to proceed.

Improving the Odds of a Successful Outcome

It is common for patients to experience problems even after small reductions in their psychotropic drugs. This is usually misattributed to a reemergence of their underlying psychiatric disorder as opposed to problems related to psychotropic drug withdrawal.1 When this happens, it is common for such patients to be shamed by family members, psychiatrists, and support workers into the notion that they cannot maintain their psychological health without depending on psychotropic drugs for the rest of their lives, thus forcing patients to continue long-term treatment.1 Darton reported that patients with mental health issues are too often denied the chance to come off their medications, take risks, and potentially make their own mistakes.9 If family members are supportive and encouraging, this will reduce risks associated with tapering psychotropic drugs.9

Diet and lifestyle modifications can also significantly improve a patient’s chances of successfully tapering off psychotropic drugs. Factors that have been identified as helpful include: (1) eating regularly; (2) avoiding sugary foods and drinks; (3) abstaining from all recreational drugs, alcohol, and possibly even caffeine; (4) establishing good sleep habits; and (5) drinking plenty of fresh water throughout the day.9,10

Supporting the Tapering Process with Specific Natural Health Products

I have found specific natural health products helpful when used during and after the tapering process to mitigate withdrawal, prevent potential relapses, and improve a patient’s chances of not requiring his/her psychotropic medication any longer.

Melatonin works well for insomnia, which is common during the tapering process. The hormone is being formally studied among schizophrenic patients withdrawing from long-term benzodiazepine use.11 Previous reports have shown some efficacy in reducing benzodiazepine-withdrawal-associated sleep disruption.12,13 Ideally, controlled- or prolonged-release preparations should be used, with doses varying from 1 to 5 mg at bedtime. If taken 1 or 2 hours before bedtime, these forms of melatonin enable a more sustained blood level of the hormone and promote sleep that tends to be deeper and less fragmented. I tend not to prescribe quick-release melatonin preparations, since they rapidly increase blood levels but do not promote a more restful and longer sleep. On occasion, I will combine a small dose (1 mg) of quick-release melatonin with a controlled- or prolonged-release preparation (3–6 mg), to facilitate quick sleep onset with sustained hormone levels to offset a broad array of sleep issues (e.g., racing mind, restlessness, and waking too early) that patients tend to experience during the tapering process.

Niacinamide (nicotinamide) can also be given to reduce withdrawal symptoms from all psychotropic drugs, since it generally “calms” the nervous system and does not possess any concerning drug interactions. It is sometimes very useful among patients withdrawing from benzodiazepines, since it possesses benzodiazepine-like effects.14 One case report demonstrated its clinical effectiveness in allowing a patient to remain clinically stable while tapering off clonazepam.14 The patient weaned himself off clonazepam in 2 weeks while increasing his daily amounts of niacinamide until he was taking 2500 mg each day. When this report was published, the patient had been free of clonazepam for 6 months and had remained stable on only the niacinamide. A written correspondence from the late Dr. William Kaufman (January 10, 1998) noted the following about the vitamin’s mechanism of action:

Niacinamide has ungated access to the brain. When it enters the brain, it has a strong affinity for the benzodiazepine receptors and causes a desirable calmative effect which you have observed. But it also improves other functions of the central nervous system.

Effective daily doses of niacinamide range from 1500 to 2500 mg. It is rarely necessary to go beyond 2500 mg, since higher doses can be associated with nausea and potentially vomiting. The mean elimination half-life in human subjects given 3000 mg of the vitamin was 5.9 ± 0.6 hours.15 Since it has such a short elimination half-life, niacinamide must be administered several times throughout the day; otherwise, its therapeutic effects will be lessened.

To stabilize mood resulting from withdrawal and to ease mood swings during tapering, I use a product called Neurapas Balance. Its therapeutic effects limit anxiety, depression, muscle tension, stress reactions, and other withdrawal reactions resulting from the tapering process. Each film-coated tablet contains 60 mg of the dry extract of Hypericum perforatum, 28 mg of the dry extract of Valerian officinalis, and 32 mg of Passiflora incarnata. There have been approximately 10 company-sponsored clinical studies (i.e., 2 controlled and 8 observational cohort studies) and 2 experience reports, which have shown this herbal combination to be safe and effective for both depression and anxiety.16 Each individual herbal extract possesses well-known postulated mechanisms of action.17 The extract of Hypericum perforatum exhibits monoamine oxidase inhibition, gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) activity, monoamine reuptake, upregulation of 5-hydroxytryptamine 1A (5-HT1A) and 5-HT2A receptors, and modulation of cytokine production. Valerian is known to have GABAergic effects. Passiflora is a partial agonist to benzodiazepine receptors. Generally, my patients start with 1 pill twice daily, and over the course of many weeks, the dose is increased to 3 pills twice daily. Even though the elimination half-life is not known for this preparation, multiple daily dosing appears to yield more optimal therapeutic outcomes.

Clinicians should not be overly concerned about adverse drug interactions, since this specific preparation contains a very low daily dose of Hypericum (i.e., 360 mg from 6 tablets) with a correspondingly low hyperforin content.18 Studies demonstrating significant pharmacokinetic drug interactions with Hypericum extracts typically involve daily dosages of 900 mg or more. At the recommended daily dose of 6 tablets, the mean amounts of hypericin and hyperforin delivered are 0.72 mg and 1.35 mg respectively. This small amount of hyperforin does not induce the major liver drug-metabolizing enzyme cytochrome P(CYP)450 3A4. Hypericum preparations containing much higher amounts of hyperforin do induce this enzyme, and those are believed to be the reason for numerous potential drug interactions. Unfortunately, the low-dose preparation is not available in the US.

Rhodiola rosea extract can also stabilize patients during psychotropic tapering. Clinical trials have shown it to attenuate mild and moderate depression, generalized anxiety, and burnout/fatigue – common withdrawal symptoms that many patients experience during tapering.19–21 It specifically works by inhibiting enzymes involved in the degradation of monoamine neurotransmitters (i.e., serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine), and this prevents the depletion of adrenal catecholamines following acute stress.22 The therapeutic dose range is somewhere between 500 and 680 mg of a standardized extract containing 3% percent total rosavins and 1% salidrosides. I normally recommend that Rhodiola rosea extract to be taken with breakfast, as it can cause considerable nausea and possibly vomiting on an empty stomach. I usually prescribe 500 mg at breakfast to stabilize mood and lessen anxiety, and will increase the daily dose to 650 to 680 mg if the patient’s response is not marked enough. Although a rat study determined the elimination half-life of salidroside in Rhodiola rosea extract to be 39.69 ± 21.02 minutes, I have not found multiple dosing throughout the day necessary.23 I doubt that the elimination half-life from the rat study correlates to the elimination half-life in humans.

There is one published report of an interaction between Rhodiola rosea extract and escitalopram.24 The case involved a 26-year-old Chinese female who presented to the emergency department with a 1-hour history of heart palpitations and light-headedness. The patient was diagnosed with supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) as per electrocardiogram findings. Her pulse rate was 150 beats per minute, and her troponin I was significantly elevated (0.39 mg/L; normal < 0.06). All other investigations were normal. She was treated with 6 mg of intravenous adenosine, which normalized her sinus rhythm. No more SVTs happened at follow-up, and her troponin I normalized in 2 days. While this case points to possible interactions between Rhodiola rosea extract and SSRI medication, I have not observed any untoward interaction when patients take them concomitantly during the tapering process. Therefore, it is important to inform all patients of this possibility and instruct them to contact you immediately should they experience a sudden onset of heart palpitations and increased heart rate.

GABA is very useful to moderate mood instability while also decreasing anxiety if given during the tapering process. Since GABA can also promote sleep, it may be given several hours before bedtime to decrease sleep fragmentation and sleep-onset problems. For patients tapering from lithium, GABA works particularly well for mood regulation. It functions as an inhibitory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system. The mechanism of GABA’s neuroinhibition is mediated through an increase in the permeability of postsynaptic membranes to chloride ions, leading to hyperpolarization. There continues to be uncertainty whether GABA can traverse the blood–brain barrier when administered orally; it appears to act on the central nervous system without crossing the blood–brain barrier.25 There are 2 forms of GABA available: crystalline GABA and PharmaGABA (produced by a fermentation process that utilizes Lactobacillus hilgardii).26 Both forms have the same molecular structure and mechanism of action, and therefore it is illogical to contend that one form somehow traverses the blood–brain barrier while another does not.25 GABA might have a therapeutic effect comparable to benzodiazepine medications and might be useful for patients addicted to them as well.27 In a case report, a 40-year-old female patient with a history of severe anxiety was able stop her diazepam and replace her lorazepam with 200 mg of GABA four times each day.27 The optimal dose of GABA is normally 2 to 3 grams daily away from meals.27 I do not use PharmaGABA due to its impracticality, for it only comes in 100 mg or 200 mg pills.

Even though side effects from GABA are rare, there is one report of neurologic tingling, flushing, and transient hypertension and tachycardia in a subject taking very high oral doses (10 grams on an empty stomach).27 Smaller oral doses (1–3 grams daily) have been reported to cause neurologic tingling and flushing in several volunteer subjects.27 PharmaGABA has been tested in rats that were administered doses of 5000 mg/kg.26 There were no deaths and the lethal dose that would likely kill at least 50% of the rat population was determined to be greater than 5000 mg/kg of body weight.

I sometimes use the amino acid L-theanine, since it can decrease anxiety and also improve focus and concentration. It is not uncommon for patients to experience disturbances in cognition during the tapering process, making this intervention potentially valuable. L-theanine presumably increases both dopamine and serotonin, although a study in rats showed that it might decrease serotonin. It also increases alpha brain-wave activity, which is associated with relaxation.28 In a study involving schizophrenic and schizoaffective disorder patients, the use of L-theanine as an augmentation strategy was associated with reductions in the following: anxiety (p = 0.015), positive symptoms (p = 0.009), and general psychopathology scores (p < 0.001).29 In another study using the same 40 patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder, the beneficial effects of L-theanine were coupled with circulating levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and the cortisol-to-dehydroepiandrosterone ratio.30 My clinical experience has shown L-theanine to mitigate destabilization while tapering from FGA and SGA drugs. The optimal dose appears to be 200 mg twice daily. There should be no side effects attributed to L-theanine, although caution might be warranted, since one of my patients is certain that it caused her to feel temporarily manic.

Numerous other natural health products could potentially be used alongside psychotropic drugs during the tapering process. Clinicians trained in clinical nutrition and botanical medicine must use discretion during psychotropic drug tapering, monitor patients’ progress carefully, mitigate potential interactions, and use available pharmacokinetic information to guide appropriate dosing.

Sample Tapering Schedules

Here are several tapering schedules that I have used in clinical practice. Each schedule was individualized to suit each patient’s needs and support mental stability. Periodic visits and regular communications (e.g., telephone calls and e-mails) are required during the tapering process so that each patient’s mental stability can be regularly assessed and warning signs of destabilization can be clinically managed to avoid more serious setbacks and/or life-threatening consequences.

Example 1

This patient was taking 25 mg of controlled-release Paxil (paroxetine) for depression. After I corresponded with her family doctor, she was switched to a 20 mg dose of Prozac (fluoxetine). The patient tolerated this switch very well. After 4 weeks on the Prozac, she was switched to a liquid form of the drug. Liquid forms allow for a more successful and gradual tapering process. Even though the tapering schedule as outlined below is much quicker than my usual process, this is what the patient requested. She did well and did not destabilize. She was eventually taken off the Neurapas Balance due to pregnancy. She is currently expecting her first child.

- Week 1: 16 mg daily of liquid Prozac and 1 pill twice daily of Neurapas Balance.

- Week 2: 12 mg daily of liquid Prozac and 1 pill three times daily of Neurapas Balance.

- Week 3: 8 mg daily of liquid Prozac and 2 pills a.m. and 2 pills p.m. of Neurapas Balance.

- Week 4: 4 mg daily of liquid Prozac and 3 pills a.m. and 3 pills p.m. of Neurapas Balance.

- Week 5+: Discontinue the liquid Prozac and remain on 3 pills a.m. and 3 pills p.m. of the Neurapas Balance.

Example 2

This patient was taking 50 mg daily of Seroquel XR (quetiapine fumarate – extended-release for depression and severe anxiety. With the cooperation of her psychiatrist, she was first switched to the non-extended-release form of Seroquel, since the 25 mg tablets can be cut into quarters (6.25 mg per quarter), making it easier to taper. The tapering process was done very gradually to mitigate instability. She is currently doing very well, and has discontinued the Seroquel without any instability or a return of her previous depression and severe anxiety.

- Week 1–3: 43.75 mg of Seroquel, 200 mg of L-theanine, and 500 mg twice daily of niacinamide.

- Weeks 4–6: 37.5 mg of Seroquel, 200 mg of L-theanine, and 500 mg three times daily of niacinamide.

- Weeks 7–9: 31.25 mg of Seroquel, 200 mg of L-theanine a.m. and 100 mg of L-theanine p.m., and 500 mg three times daily of niacinamide.

- Weeks 10–12: 25 mg of Seroquel, 200 mg of L-theanine twice daily, and 1000 mg of niacinamide twice daily. Instructed to add 1.5 mg of prolonged-release melatonin (PRM) 60 minutes before bed.

- Weeks 13–15: 18.75 mg of Seroquel, 200 mg of L-theanine twice daily, 1500 mg of niacinamide at breakfast, and 1000 mg at dinner. Continued with 1.5 mg of PRM 60 minutes before bed.

- Weeks 16–18: 12.5 mg of Seroquel, 200 mg of L-theanine twice daily, 1500 mg of niacinamide breakfast, and 1000 mg dinner. Increase to 3.0 mg of PRM 60 minutes before bed.

- Weeks 19–21: 6.25 mg of Seroquel, 200 mg of L-theanine twice daily, 1500 mg of niacinamide breakfast, and 1000 mg dinner. Continue with 3.0 mg of PRM 60 minutes before bed.

- Week 22+: Discontinue the Seroquel, continue with 200 mg of L-theanine twice daily, and 1500 mg of niacinamide breakfast, and 1000 mg dinner. Continue with 3.0 mg of PRM 60 minutes before bed.

Example 3

This stable schizophrenic patient had been on SGA drugs for 5 years prior to seeing me. She had been on olanzapine for about 1 year and then, due to objectionable side effects, was switched to 5 mg of loxapine daily. Since she had a mild form of schizophrenia, her daily dose of loxapine was well below doses typically used for more severe forms of the disorder (e.g., 30–50 mg twice daily or more). She attributed chronic stomach pain, fatigue, and dizziness to the medication and wanted to stop it. I corresponded with her psychiatrist and we agreed that the patient was stable enough to pursue my tapering plan. In addition to tapering, I further supported her mental health by adding an orthomolecular program providing daily dosages of niacin (3000 mg), vitamin C (3000 mg), omega-3 essential fatty acids (1500 mg of eicosapentaenoic acid and 500 mg of docosahexaenoic acid), and N-acetylcysteine (1000 mg). The patient is now completely off the loxapine and has not had a return of previous psychotic symptoms, which were auditory hallucinations and paranoid ideation. She has agreed to remain on the orthomolecular program for life. All of the physical symptoms that she ascribed to the loxapine ameliorated as well.

- Weeks 1–3: 5 mg loxapine every other day and 1 pill daily of Neurapas Balance.

- Weeks 4–6: 5 mg loxapine every 2 days and 1 pill daily of Neurapas Balance.

- Weeks 7–9: 5 mg loxapine every 3 days and 1 pill twice daily of Neurapas Balance.

- Weeks 10–12: 5 mg loxapine every 4 days and 1 pill twice daily of Neurapas Balance.

- Weeks 13–15: 5 mg loxapine every 5 days and 2 pills of Neurapas Balance in the a.m. each day and 1 pill in the p.m. each day.

- Weeks 16–18: 5 mg loxapine every 6 days and 2 pills of Neurapas Balance in the a.m. each day and 2 pills in the p.m. each day.

- Weeks 19–21: 5 mg loxapine every 7 days and 3 pills of Neurapas Balance in the a.m. each day and 2 pills in the p.m. each day.

- Weeks 22+: No more loxapine and 3 pills of Neurapas Balance a.m. each day and 3 pills p.m. each day for a minimum of 3 months.

Clinical Considerations

Some patients may wish to taper; that is, reduce their doses to reduce side effects but retain benefits of particular medications, while other patients may wish to go off their medications altogether. Sometimes a patient needs a very low dose of a particular medication to remain stable. Thus, the tapering strategy should always consider this possibility. Patient expectations must be managed with clinical vigilance and education; otherwise, the stabilizing benefit of a very low-dose medication might be undermined by the patient’s unrealistic wish to be completely free of his medication. The tapering process can teach such patients the value of continuing to take very low doses, and respect the reality that some patients will need low doses of one or more medications for the duration of their lives.

Bipolar patients who successfully go off their medications altogether are potentially at risk for cycling again into hypomania or outright mania. Schizophrenia patients who successfully go off their medications altogether are potentially at risk for a return of psychosis; therefore, in my experience, it is important for patients to understand and accept their diagnosis and know that they will need to continue taking specific combinations of natural medicines (i.e., a supervised plan of botanical medicines, nutrients such as vitamins, minerals, amino acids, and/or hormones) for life to sustain their mental stability.

Given life’s uncertainties and the fact that all patients will experience periods wherein their emotional regulation and mental stability are challenged, clinicians should secure regular reassessments with their patients during the first 1 or 2 years after being off psychotropic medication. Clinicians should inform patients that they can temporarily benefit from resuming medication as needed should their circumstances warrant the immediate relief and stability afforded by medication. Clinicians should routinely check for thyroid, blood sugar, and hormone imbalances; that is, underlying medical or metabolic conditions which may have been root cause(s) or contributed to some of their patients’ anxious, intense moods in the first place. This continuity between clinician and patient affords the best long-term outcome, since these particularly vulnerable patients need to have a trusting ally in their quest for improved physical and mental health.

Above all, none of the strategies outlined in this article are meant to be adopted without consulting a clinician experienced in psychotropic drug tapering. Patients should not attempt to taper from their psychotropic drugs and experience withdrawal without proper guidance and regular clinical supervision; otherwise, it is very possible to deteriorate, destabilize, and in worst cases, commit suicide.

Conclusion

Helping patients taper their psychotropic drugs is complicated by many factors, including their stability, support system, and the length of time they have been on psychotropic drugs. This is also controversial, since family doctors and psychiatrists often oppose tapering due to concerns of ongoing stability, and their beliefs that psychotropic drugs are required over the long term. From my perspective, mentally competent patients have the right to choose what they think is best, even if such beliefs are not held by their prescribing clinicians. This article should assist and empower clinicians to develop effective tapering strategies on behalf of their willing and mentally competent patients.

Acknowledgements

I thank Mr. Bob Sealey for his helpful editing suggestions and input on the contents of this paper. Written consent was obtained from each patient for publication of the tapering schedules in this article.

Competing Interests

Dr. Prousky is a consultant for Pascoe Canada, the distributor of Neurapas Balance. All of the tapering schedules described in this article were developed prior to Dr. Prousky’s consultancy with Pascoe Canada.

Jonathan E. Prousky, ND, MSc

Chief Naturopathic Medical Officer, Professor Canadian College of Naturopathic Medicine

1255 Sheppard Ave. East

Toronto, Ontario, M2K 1E2 Canada

416-498-1255, ext. 235

jprousky@ccnm.edu

Editor, Journal of Orthomolecular Medicine

The contents of this article have been considerably expanded upon since its original publication in: Integrated Healthcare Practitioners. 2012;5(1):56–59.

Permission has been granted from Integrated Healthcare Practitioners for publication of this article.