Erik Peper, PhD

I quickly gasped twice, and a sharp pain radiated up my head and into my eye. I shifted to slow breathing, and it faded away.

I felt anxious and became aware of my heart palpitations at the end of practicing 70% exhalation for 30 seconds. I was very surprised how quickly my anxiety was triggered when I changed my breathing pattern.

Breathing is the body/mind/emotion/spirit interface which is reflected in our language with phrases such as a sigh of relief, all choked up, breathless, full of hot air, waiting with bated breath, inspired or expired, all puffed up, breathing room, or it takes my breath away. The colloquial phrases reflect that breathing is more than gas exchange and may have the following effects.

- Changes the lymph and venous blood return from the abdomen.1 The downward movement of the diaphragm with the corresponding expansion of the abdomen occurs during inhalation as well as slight relaxation of the pelvic floor. The constriction of the abdomen and slight tightening of the pelvic floor causing the diaphragm to go upward and allows exhalation. This dynamic movement increases and decreases internal abdominal and thoracic pressures and acts a pump to facilitate the venous and lymph return from the abdomen. In many people this dynamic pumping action is reduced because the abdomen does not expand during inhalation as it is constricted by tight clothing (designer jean syndrome), holding the abdomen in to maintain a slim self-image, tightening the abdomen in response to fear, or the result of learned disuse to reduce pain from abdominal surgery, gastrointestinal disorders, or abdominal insults.2

- Increases spinal disk movement. Effortless diaphragmatic breathing is a whole-body process and associated with improved functional movement.3 The spine slightly flexes when we exhale and extends when we inhale, which allows dynamic disk movement unless we sit in a chair.

- Communicates our emotional state as our breathing patterns reflect our emotional state. When we are anxious or fearful the breath usually quickens and becomes shallow while when we relax the breath slows and the movement is more in the abdomen.4

- Evokes, maintains, inhibits symptoms or promotes healing. Breathing changes our physiology, thoughts, and emotions. When breathing slowly to about six breaths a minute, it may enhance heart rate variability and thereby increase sympathetic and parasympathetic balance.5,6

Can Breathing Trigger Symptoms?

A 55-year-old woman asked for suggestions what she could do to prevent the occurrence of episodic prodrome and aura symptoms of visual disturbances and problems in concentration that would signal the onset of a migraine. In the past, she had learned to control her migraines with biofeedback; however, she now experienced these prodromal sensations more and more frequently without experiencing the migraine. As she was talking, I observed that she was slightly gasping before speaking with shallow rapid breathing in her chest.

To explore whether breathing pattern may contribute to evoke, maintain or amplify symptoms, the following two behavioral breathing challenges can suggest whether breathing is a factor: Rapid fearful gasping or 70% exhalation.

Behavioral Breathing Challenge: Rapid, Fearful Gasping

Take a rapid fearful gasp when inhaling as if your feel scared or fearful. Let the air really quickly come in and repeat two or three times. (See March 24, 2019 blog post.) Then describe what you experienced.

If you became aware of the onset of a symptom or that the symptom intensified, then your dysfunctional breathing patterns (e.g., gasping, breath holding or shallow chest breathing) may contribute to development or maintenance of these symptoms. For many people when they gasp–a big rapid inhalation as if they are terrified–it may evoke their specific symptom such as a pain sensation in the back of the eye, slight pain in the neck, blanking out, not being able to think clearly, tightness and stiffness in their back, or even an increase in achiness in their joints.7

To reduce or avoid triggering the symptom, breathe diaphragmatically without effort; namely each time you gasp, hold your breath or breathe shallowly, shift to effortless diaphragmatic breathing.

In the above case of the woman with the prodromal migraine symptoms, she experienced visual disturbances and fuzziness in her head after the gasping. This experience allowed her to realize that her breathing style could be a contributing in triggering her symptoms. When she then practiced slow diaphragmatic breathing for a few breaths, her symptoms disappeared. Hopefully, if she replaces gasping and shallow breathing with effortless diaphragmatic breathing, then there is a possibility that her symptoms may no longer occur.

Behavioral Breathing Challenge: 70% Exhalation

While sitting, breathe normally for a minute. Now change your breathing pattern so that you exhale only 70% or your previous inhaled air. Each time you exhale, exhale only 70% of the inhaled volume. If you need to stop, just stop, and then return to this breathing pattern again by exhaling only 70 percent of the inhaled volume of air. After 30 seconds, let go and breathe normally (as guided by the video clip). Observe what happened?

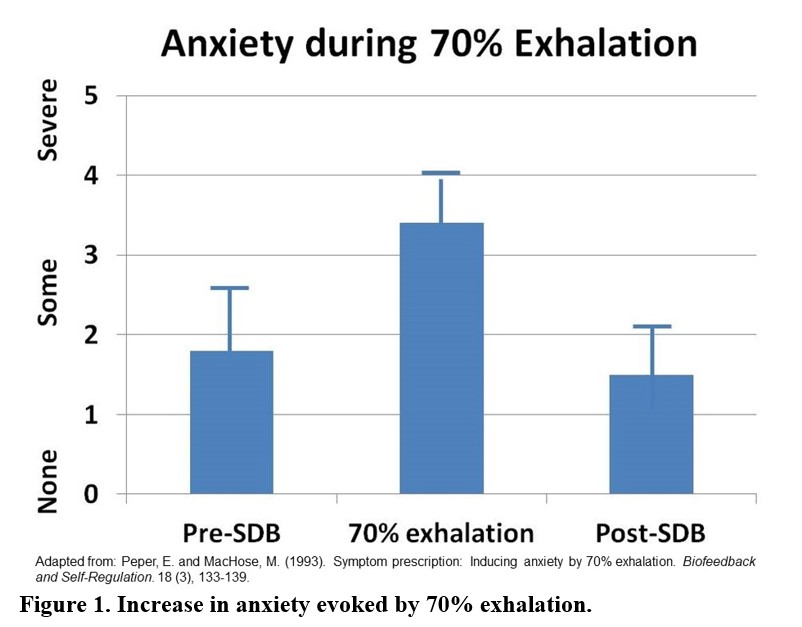

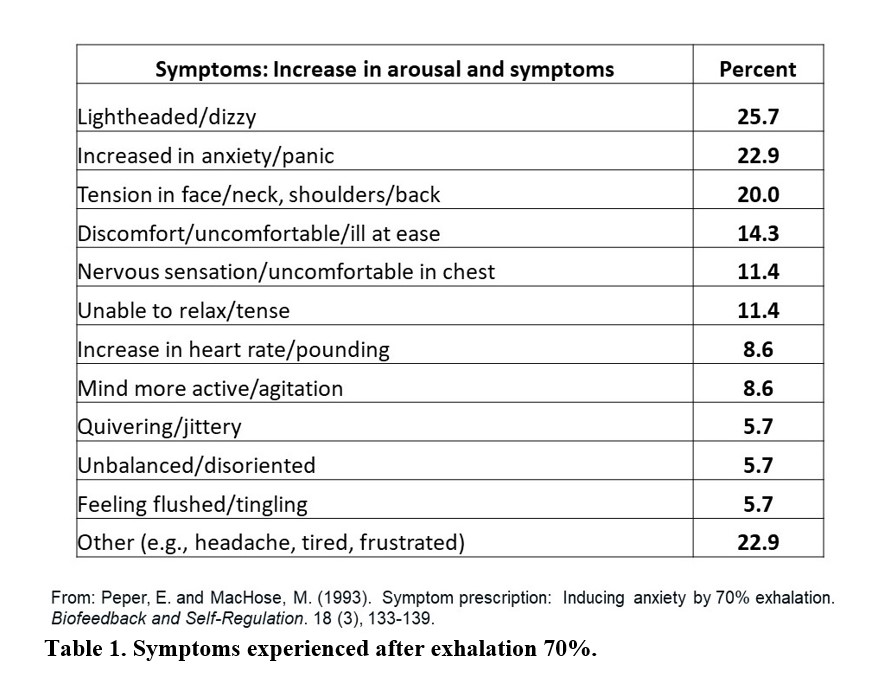

In our research study with 35 volunteers, almost all participants experienced an increase in arousal and symptoms such as lightheadedness, dizziness, anxiety, breathless, neck and shoulder tension after 30 seconds of incomplete exhalation as shown in Figure 1 and Table 1.8

Although these symptoms may be similar to those evoked by hyperventilation and over-breathing, they are probably not caused by the reduction of end-tidal carbon dioxide (CO2). The apparent decrease in end-tidal PCO2 is cause by the room air mixing with the exhaled air and not a measure of end-tidal CO2.9 Most likely the symptoms are associated by the shallow breathing that occurs when we were scared or terrified.

People who have a history of anxiety, panic, nervousness, and tension as compared to those who report low anxiety tend to report more symptoms when exhaling 70% of inhaled air for 30 seconds. If this practice evoked symptoms, then changing the breathing patterns to slower diaphragmatic breathing may be a useful self-regulation strategy to optimize health.

These two behavior breathing challenges are useful demonstrations for students and clients that breathing patterns can influence symptoms. By experiencing ON and OFF control over their symptoms with breathing, the person now knows that breathing can affect their health and wellbeing.

References

- Piller, N., Leduc, A., & Ryan, T. (2006). Does breathing have an influence on lymphatic drainage? Journal of Lymphoedema, 1(1), 86-88.

- Peper, E., Gilbert, C.D., Harvey, R. & Lin, I-M. (2015). Did you ask about abdominal surgery or injury? A learned disuse risk factor for breathing dysfunction. Biofeedback. 34(4), 173-179. DOI: 10.5298/1081-5937-43.4.06

- Bradley, H. & Esformes, J. (2014). Breathing pattern disorders and functional movement. International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy, 9(1), 28-39.

- Homma, I. & Masoka, Y. (2008). Breathing rhythms and emotions. Experimental Physiology, 93(9), 1011-1021.

- Lehrer, P.M. & Gevirtz, R. (2014). Heart rate variability biofeedback: how and why does it work? Frontiers in Psychology, 5

- Moss, D. & Shaffer, F. (2017). The application of heart rate variability biofeedback to medical and mental health disorders. Biofeedback, 45(1), 2-8.

- Peper, E., Lee, S., Harvey, R., & Lin, I-M. (2016). Breathing and math performance: Implication for performance and neurotherapy. NeuroRegulation, 3(4),142–149.

- Peper, E. & MacHose, M. (1993). Symptom prescription: Inducing anxiety by 70% exhalation. Biofeedback and Self-Regulation. 18(3), 133-139.

- Peper, E. & Tibbetts, V. (1992). The effect of 70% exhalation and thoracic breathing upon end-tidal C02. Proceedings of the Twenty-Third Annual Meeting of the Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. Wheat Ridge, CO: AAPB, 126-129. Abstract in: Biofeedback and Self-Regulation. 17(4), 333-334.

Resources for Learning Effortless Diaphragmatic Breathing

About the Author

Erik Peper, PhD, is an international authority on biofeedback and self-regulation. Since 1970 he has been researching factors that promote healing. Peper is Professor of Holistic Health Studies/Department of Health Education at San Francisco State University. He is President of the Biofeedback Foundation of Europe and past President of the Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. He holds Senior Fellow (Biofeedback) certification from the Biofeedback Certification Institute of America. He has a biofeedback practice at Biofeedback Health (www.biofeedbackhealth.org) and posts articles at https://peperperspective.com.