by David I. Minkoff, MD, Julie Mayer Hunt, DC, DICCP, FCCJP, and Ron Tribell

For the past 20 years I have worked with patients who have had a chronic illness. From mercury toxicity, to Lyme, autoimmune disease, and cancer, I had a stable model with which to approach them; and about 85% of the time I was successful in helping them toward healing and recovery. This approach boiled down to two basic problems. They had 1) things in their body that should not be there (toxicity/infection), and they had 2) things missing from their body that should be there: deficiency. With my early training in neural therapy, I would also address some of the structural aspects that would impair autonomic function such as scars and ganglion blockage or toxic root canal teeth or cavitations. With the four-component theory of disease 1) structure; 2) biochemical/microbiological; 3) autonomic balance; 4) spiritual, I thought I had things well understood and under control.

I was familiar with the chiropractic model of subluxation impairing nerve function, but it was out of my expertise range; and I would refer when I thought it appropriate, but usually only as an afterthought. As a medical doctor my orientation was on “more important” things that cause body disease and illness. Little did I know that there was a very significant part of the structural aspects of health that I knew nothing about nor had any inkling of how significant it was. But that was not until I met my mentor, Dr. Julie Mayer Hunt, DC, DICCP, FCCJP, a world expert in the subject; and we have partnered in helping hundreds of patients that I have referred to her for care.

How many patients do you see with headaches, head pressure, neck pain, migraine, tinnitus, vertigo, POTS, brain fog, memory loss, multiple sclerosis (MS), Parkinson’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and Alzheimer’s disease? In how many of those have you considered that they had a structural problem at their cranial cervical junction (CCJ) that either contributed to their condition or was the actual cause of it? What is CCJ? More on that shortly.

It was only a couple of years ago that I met Dr. Julie Hunt quite by accident when a patient told me she had seen her and got an amazing change in her condition of constant head pressure of 15 years following a whiplash injury. Dr. Hunt comes from a family of upper cervical chiropractors. Her dad started their practice 60 years ago, and now Julie, her father, and her son all work together as upper cervical specialists. They are only blocks from my office, and little did I know the miracles that they produce. Because of the incredible impact of upper cervical treatment of the CCJ on my practice, I decided to partner with Dr. Hunt in writing this article to bring awareness of how common this problem is. I knew that if I was a medical doctor working with patients who had chronic illness for 20 years and had no idea of how important it was in health, that there were thousands more like me who would appreciate knowing the science so they could help their patients better. That is the purpose of this article.

Anatomy and Physiology of the Craniocervical Junction (CCJ)

To understand what craniocervical junction (CCJ) chiropractic care encompasses, a review of the basic anatomy is the starting point. The CCJ is the most complex joint region in the body. The CCJ, also referred to as the cranio-vertebral junction, is a collective term that refers to the occiput (posterior skull base), atlas, axis, and very importantly, the supporting ligaments.

It is a transitional zone between a relatively rigid cranium and a mobile spinal column enclosing the soft tissue of the brainstem at the cervicomedullary junction (medulla, brainstem and spinal cord). It is critical to fully understand the neurology, biomechanics, and soft tissue integrity, including ligaments,(1) blood flow, and cerebral spinal fluid flow at the junction between the brain and the body.(2) Figure 1a provides details of the CCJ and the associated anterior supporting structures, including the alar ligaments, the apical ligament tectorial membrane, anterior atlanto-occipital and atlantoaxial membranes. The posterior supporting ligaments are comprised of the posterior atlanto-occipital membrane and atlantoaxial ligament. Figure 1b shows possible post trauma disruption of the posterior stabilizing ligaments of the CCJ.

As shown in Figure 2, the vascular parameters of the CCJ include the vertebral arteries which pass through the transverse processes of the atlas and make a total of four ninety degree turns. Additionally, the internal jugular veins pass just anterior to the transverse processes of the atlas vertebrae.(4) The positioning of the segments of the CCJ affect blood flow and cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) fluid flow dynamics to and from the brain.

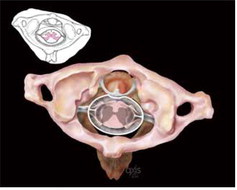

Key biomechanical stabilizers of the brainstem inside the spinal column are the dentate ligaments. These ligaments begin at the atlas level and are responsible for centering the base of the brainstem and spinal cord throughout the spinal canal.  Particularly when the CCJ structures are misaligned, the dentate ligaments can create adverse tension on the lateral aspects of the spinal cord, affecting neurological impulses throughout the body and distorting the spinal cord. MRI axial presentation can be from round (normal) to almost football-shaped (abnormal), observable upon MRI imaging of the CCJ. This is shown in Figure 3 where the picture on the left shows a normal round view of the brainstem while the picture on the right shows the football shape distortion of the brainstem caused by dentate ligament tension.

Particularly when the CCJ structures are misaligned, the dentate ligaments can create adverse tension on the lateral aspects of the spinal cord, affecting neurological impulses throughout the body and distorting the spinal cord. MRI axial presentation can be from round (normal) to almost football-shaped (abnormal), observable upon MRI imaging of the CCJ. This is shown in Figure 3 where the picture on the left shows a normal round view of the brainstem while the picture on the right shows the football shape distortion of the brainstem caused by dentate ligament tension.

The base of the brain has cerebellar tonsils, which in large part are responsible for our balance and coordination. The brain and spinal cord are one unit. Think of the spinal cord as a long-braided ponytail; it is an extension of the brain. When the base of the skull and the atlas/axis become misaligned, the dentate ligaments supporting and protecting the brainstem can potentially produce caudal tension at the skull base, creating a downward tug at the brain base. The CCJ is the main circuit breaker neurologically as well as being the “mouth” to the brain for fluid exchange, including both CSF and blood. The CCJ is best imaged upright to observe true functional positioning of key components such as the cerebellar tonsils. When MRI imaging is done in a supine fashion, the back of the head can act like something of a “bowl” and the brain tissue tends to slide into the bottom of the bowl. When MRI imaging is performed upright, the brain tissue may occupy a different position; also, spinal misalignments can be observed.

Chiari malformation is a serious neurological disorder where the bottom part of the brain (cerebellar tonsils) descend into the foramen magnum, crowding the brainstem/spinal cord and altering CSF flow dynamics, producing many disabling symptoms. Cerebellar tonsil position is commonly measured using the basion-opisthion line (B-OL, also known as the McRae Line), shown in Figure 4.

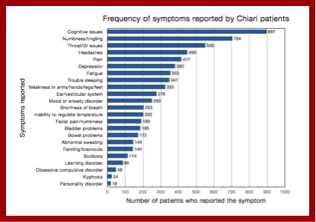

When the cerebellar tonsils descend five (5) mm or less below the basion-opisthion line (skull base) and into the spinal canal, this is referred to as cerebellar tonsular ectopia (CTE) and may be listed as Chiari 0 or borderline Chiari 1 depending on the exact measurement. A Chiari 1 is measured as more than five (5) mm descent of the tonsils into the spinal canal. Symptoms can vary greatly from one person to another, and some patients may be asymptomatic until a trauma occurs.(6) The most common symptoms include cognitive issues, neck pain, headaches, visual abnormalities, poor coordination, difficulty swallowing, nausea, dizziness, anxiety, and depression as shown in Fig. 5.(7)

Anatomical illustrations of the CCJ3 are provided showing normal cerebellar tonsil positioning (Figure 6A) and low-lying cerebellar tonsils (Figure 6B). The low-lying cerebellar tonsils can potentially block cerebral spinal fluid flow and therefore affect brain health and neuroimmune function.

Anatomical illustrations of the CCJ3 are provided showing normal cerebellar tonsil positioning (Figure 6A) and low-lying cerebellar tonsils (Figure 6B). The low-lying cerebellar tonsils can potentially block cerebral spinal fluid flow and therefore affect brain health and neuroimmune function.

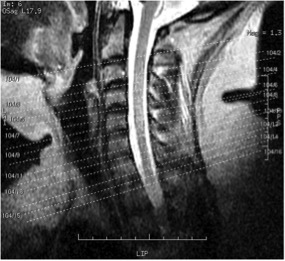

Sagittal MRI imaging depicting normal cerebellar position at the CCJ (Figure 7A) and abnormal cerebellar position affecting CCJ CSF fluid mechanics and brain health potential at the CCJ figure (Figure 7B) are provided as additional real-world depictions of the illustrations in Figure 6.2

With respect to the craniocervical junction (CCJ), most standard MRI imaging does not observe this region sufficiently. Standard axial brain MRI imaging usually terminates a slice or two under the skull base.(8) Standard axial imaging of the cervical spine usually begins at the C2 disc and proceeds caudally to the C7 region as depicted in Figure 8. Sagittal cervical MRI imaging are usually four (4) to five (5) millimeter slices which can miss detailed structures of the CCJ like cerebellar tonsils, which are small peg-like structures at the base of the brain, and CCJ ligaments, which average two (2) mm in diameter. Therefore, the CCJ soft tissue has been routinely overlooked in the mainstream medical community. Keep in mind that the medical acronym WNL, normally meaning “within normal limits,” can also mean “we never looked.” CCJ imaging in the past has utilized computerized tomography (CT) to rule out fracture without soft tissue considerations.(9)

CCJ Imaging Methods

For CCJ MRI imaging, the benefits of upright versus supine imaging were discussed earlier in this article. For the recommended upright imaging, patients are seated; and images are obtained on the coronal, sagittal and axial planes (depicted in Figure 9) using sequences as shown in Figure 10. In these sequences:

The slice thickness in these cases should be a maximum of 2.8 mm.

- The axial slices were obtained in proton density (PD), which is best to see ligaments.

- The sagittal slices were obtained in T1 (longitudinal relaxation time) and T2 (transverse relaxation time).

- Coronal images were obtained in T1.

Upright MRI imaging of the CCJ revealing low cerebellar tonsils in all three planes is shown in the Figure 11. This positioning may obstruct the normal flow of CSF. CFS obstruction may contribute to headaches, head pressure, dizziness, brain fog, and the like.

Atlas Rotation Observations: When the atlas rotates, it is plausible anatomically that the transverse process can abut the internal jugular vein. Figure 12 depicts two examples of atlas rotation misalignment. The red line highlights the rotation. The yellow arrow points to an internal jugular, which appears to have been compressed by the misaligned atlas. This compression can potentially affect venous outflow from the brain, causing backup of venous metabolic waste blood in the brain which is suggested in neurodegenerative brain diseases.(10) Also note the football shape versus a normal, round shape of the spinal cord which plausibly can suggest dentate ligament attachment tension at the brainstem.5,(11)

C2 (Axis) rotation can be observed on CCJ oriented MRIs. Figure 13 provides several examples of axial rotational misalignment. The standard medical community cervical spine MRI misses this segment because the slices start at the C2/C3 disc. When one considers the vertebral artery pathway, illustrated in Figure 2, the axial misalignment can plausibly correlate with vertebral artery insufficiency and also the misalignments can affect dentate ligament tension of the spinal cord.(5,11)

C1 misalignment can be observed in the sagittal view with respect to the occipital condyles and the atlas lateral mass position. Figure 14a suggests anterior misalignment of the atlas lateral mass with respect to the occipital condyle. Figure 14b depicts a normal positioning of the C0/C1 articulation.(13)

Observations that can be made through upright MRI have the potential to clearly objectify spinal misalignment (Subluxation) and clarify patient care needs. The CCJ is a vulnerable region and merits special consideration for care and treatment. There are many parameters for studying the CCJ through MRI which can range from CSF and blood flow impedance, ligamentous laxity and or insufficiency, and cerebellar tonsular ectopia as well as Chiari involvement.(13)

In 2012 the glymphatic system was postulated(14) with regards to lymphatic drainage and brain health. The lymphatic system that was discovered in the brain is dependent on CSF flow. The glymphatic system, as shown in Figure 15, above, is a functional waste clearance pathway for the central nervous system. The CSF flow, when obstructed, appears to have negative plausible effects on brain health. Therefore, having the CCJ aligned contributes to non-obstructed flow of CSF and will plausibly contribute to improved brain health and immune function.

Craniocervical Syndrome Case Studies

Study 1, Pediatric Syrinx: A 14-year-old male presented in the office following ten days of hospitalization at a Johns Hopkins affiliated children’s hospital facility for severe head, neck, and upper extremity pain and sensitivity. On release, it was explained to him and his family that hospital protocol had been exhausted and his pain was hormonal. MRI imaging inclusive of the CCJ was ordered the day after his hospital release, which revealed a large syrinx and cerebellar tonsillar ectopia (CTE) with CCJ misalignment. We postulate that the CCJ misalignment affected the CSF hydrodynamics and the misdirected CSF played a major role in formation of the syrinx. The MRI images in Figure 16 show the location and magnitude of the syrinx as well as showing the CTE. As treatment, CCJ realignment was performed and additional CSF flow imaging was obtained and utilized in the CCJ correction. The patient resolved successfully with this treatment.

Study 2, Chiari: A 19-year-old female presented to the office with eye-popping headaches, dizziness, and brain fog, which had been unremitting for the previous ten years since she had fallen on her head from a gymnastics uneven bar. She had an exhaustive list of neuro-medical consults which had provided no diagnosis or relief. She was told her issues “were all in her head.” An MRI was ordered and revealed a Chiari of 22 millimeters as highlighted by the arrows in Figure 17.

She responded fairly well to CCJ specific care for three years, but ultimately had a decompression procedure that has been successful.

Study 3,

Concussive Headaches: A 14-year-old male presented with constant severe head and neck pain following a concussion. MRI CCJ imaging was ordered, but the parents delayed obtaining the imaging for months. Ultimately, when the imaging was performed, shown in Figure 18, a torn transverse ligament was discerned. The atlanto dental interspace is unequal (note the difference in spacing between the red marked and unmarked sides in the figure) therefore appropriate care inclusive of CCJ facet blocks are considered and possible CCJ stem cell therapy. CCJ instability is a strong consideration for his symptomatology, and the brainstem is football shaped due to dentate ligament traction parameters versus a normal round shape

Study 4, Childhood Constipation: A six-year-old male presented for treatment post-motor-vehicle accident (MVA). He presented with typical neck, head, and back post-traumatic injuries. The clinical findings included unilateral erector spinae marked spasms and spinal imbalance, with a leg length discrepancy of just over ¾”. Figure 19 illustrates the possible effects on the body related to subluxation of the upper cervical spine.

Palpation of the upper cervical spine revealed unilateral articular joint pain. Figure 20 shows CCJ x-rays pre (left) and post (right) adjustment with orthospinology specific analysis of the misalignment. Post upper cervical adjustment, the upper cervical misalignment is reduced and unilateral erector spinae spasm is released and the leg length discrepancy is balanced, resolving the MVA symptomology with upper cervical chiropractic care. In addition to his injuries resolving, his mother reported that his painful constipation, experienced since birth, had also resolved under care. Balancing the central nervous system with upper cervical chiropractic care allows the body to neurologically repair itself.

Conclusion

Trauma continues to be a major player in the disruption of the CCJ integrity. Birth trauma, falls, motor vehicle crashes, sports injuries, and other traumas affecting the head and neck relationship throughout our lives play into the ability of the CCJ to facilitate the brain/body connection. All patients deserve an appropriate evaluation of the CCJ for optimal brain health parameters and brain/body for our health. There is much more that needs to be studied and understood to optimize brain health. The upright MRI imaging is a platform that potentially could allow neurology, neuroradiology and other medical specialties to work together with board-certified chiropractic CCJ procedure specialists to benefit patients and families. Understanding the complexities of the CCJ should compel all health practitioners to study further and understand how to optimize the brain/body communication of the most critical joint region of the body.

Parting Thoughts

I’d like to emphasize guidelines for practitioners who are on the front line to have high index of suspicion when they see patients with history of head or neck trauma, or autonomic symptoms involving the brain stem or cranial nerves, vertigo, brain fog, head pressure or pain of any kind, or anything from chronic constipation to cardiac arrhythmias. Autistic children should all be referred as early as possible.

Unfortunately, there is an epidemic of young infants being diagnosed with GERD by pediatricians and pediatric gastroenterologists. These infants are symptomatic, but to put a two-month-old baby, who has just been through a birth process that more than likely affected his CCJ, on Pepcid or similar acid blocking drug is not good medicine, especially if his problem can be cured with a couple of gentle movements to his upper cervical spine.

Once the brain has been decompressed and CSF flow re-established, then detoxification and healing can occur if the required nutrients are supplied. Primary to this are essential amino acids and essential fatty acids with vitamins and minerals. Neurons that have been under stress require optimal nutrition to heal. My standard approach for supplying required nutrients consists of the following:

- Paleo or Ketogenic diet,

- Supplemental amino acids in the form of Perfect Amino,

- Omega 3 supplement,

- Probiotic,

- Complete multivitamin like BodyHealth Complete that contains 5000 u Vitamin D3 and K and activated folate.

- If chemical or heavy metal toxicity is part of the picture, then Metal Free and Body Detox can be added.

In summary, it is the doctor’s obligation to find the actual diagnosis that the patient has if he is to help the patient. All too often in complex cases the workup by the traditional doctor is too superficial to really do this and patients get put on symptomatic medication that has no chance of reversing the process, and a good chance that the medication will further complicate the problem. Meanwhile the actual cause has never been found.

It is my experience now that very few doctors consider that CCJ pathology could be the underlying cause and, without knowing this, never pursue this as a possible diagnosis. Dr. Hunt and her team have trained up an expanding group of doctors who know this technology and who can be consulted to help you out.

Whenever I hear on my initial interview any of the symptoms from the patient listed in Figure 5, I refer them to the upper cervical specialist for proper exam and, if needed, X-rays to confirm if there is a problem at the CCJ. This has been the most significant breakthrough in my education in many years, and it has upgraded my success results with patients tremendously. For me this has meant an upgrade in my listening skills so that when the patient mentions a key symptom(s) or answers one of my questions that my index of suspicion jumps into action and I refer them.

I know if you learn from this to listen for it and pursue it, it will do the same for you.

Good luck,

Drs. Minkoff and Hunt

References

1. Kahn, A.N (Chief Editor), et al. Upper Cervical Spine Trauma Imaging. Medscape; Online Article 397563; 2015

2. Freeman MD, et al.; A case-control study of cerebellar tonsillar ectopia (Chiari) and head/neck trauma (whiplash); Brain Injury; July 2010; 24(7-8): 988-994

3. Illustrations courtesy of Ron Tribell; Medical Illustrator; Axis Arts; Little Rock, AR

4. Bulut MD, et. al. Decreased Vertebral Artery Hemodynamics in Patients with Loss of Cervical Lordosis. Medical Science Monitor. 2016; 22:495-500; e-ISSN 1643-3750, http://www.medscimonit.com/abstract/index/idArt/897500

5. Eriksen K. Upper Cervical Subluxation Complex: A Review of the Chiropractic and Medical Literature. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2003

6. Flanagan MF. The Role of the Craniocervical Junction in Craniospinal Hydrodynamics and Neurodegenerative Conditions. Neurology Research International. 2015;Article ID 794829.

7. Fischbein R, et al. Patient-reported Chiari malformation type I symptoms and diagnostic experiences: a report from the national Conquer Chiari Patient Registry database. Neurological Sciences. 2015;36(9):1617-24.

8. Parizel PM, et al. Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Brain. In: Clinical MR Imaging, P.Reimer et al. (eds.); Springer-Verlag; 2010

9. Riacos R, et al. Imaging of Atlanto-Occipital and Atlantoaxial Traumatic Injuries: What the Radiologist Needs to Know. RadioGraphics. 2015; 35:2121-2134.

10. Flanagan MF. Craniospinal Hydrodynamics in Neurodegenerative and Neurological Disorders; Nova Science Publishers, Inc.; 2016

11. Grostic JD. Dentate Ligament – cord distortion hypothesis. Chiropractic Research Journal. 1988;1(1): 47-55.

12. Rosa S, Baird JW. The Craniocervical Junction: Observations regarding the Relationship between Misalignment, Obstruction of Cerebrospinal Fluid Flow, Cerebellar Tonsillar Ectopia, and Image-Guided Correction. In: The Craniocervical Syndrome, Smith, F.W. and Dworkin, J.S Editors; Karger; 2015; pages 48-66

13. Iliff JF, et al. A Paravascular Pathway Facilitates CSF Flow Through the Brain Parenchyma and the Clearance of Interstitial Solutes, Including Amyloid β. Science Translational Medicine. 15 Aug 2012:4(147): 147.

14. Hunt JM. Observations at the Craniocervical Junction Using Upright MRI. The Chiropractic Choice (ICA digital magazine). April 2017.

Acknowledgements

Parts of this paper ‘borrow’ content from a paper written by Dr. Hunt for the International Chiropractors Association (ICA) digital magazine, The Chiropractic Choice, reference 14. Dr. Hunt thanks the ICA for allowing use of this content. Dr. Hunt also acknowledges the excellent illustration inputs from Ron Tribell of Axis Arts (reference 3) which help visualize the most complex joint region of the body.

Dr. David Minkoff graduated from the University of Wisconsin Medical School in 1974 and was elected to the “Phi Beta Kappa” of medical schools, the prestigious Alpha Omega Alpha Honors Medical Fraternity for very high academic achievement. He then worked for more than 20 years in the area of traditional medicine before making the switch to alternative medicine when he and his wife, Sue, founded LifeWorks Wellness Center in Clearwater, Florida. LifeWorks is now one of this country’s foremost alternative health clinics, offering a wide range of cutting-edge protocols.

Dr. David Minkoff graduated from the University of Wisconsin Medical School in 1974 and was elected to the “Phi Beta Kappa” of medical schools, the prestigious Alpha Omega Alpha Honors Medical Fraternity for very high academic achievement. He then worked for more than 20 years in the area of traditional medicine before making the switch to alternative medicine when he and his wife, Sue, founded LifeWorks Wellness Center in Clearwater, Florida. LifeWorks is now one of this country’s foremost alternative health clinics, offering a wide range of cutting-edge protocols.

In 2000, Dr. Minkoff founded BodyHealth, a nutrition company which offers a unique range of dietary supplements to the public and practitioners. Dr. Minkoff is passionate about fitness and is a 42-time Ironman finisher, including eight appearances at the Ironman World Championships in Hawaii. He also writes two weekly newsletters, The Optimum Health Report and the BodyHealth Fitness Newsletter.

Dr. Julie Mayer Hunt is a second-generation upper cervical care chiropractor in Clearwater, Florida. She graduated from Life University in 1981 and started practicing with her father, Dr. David Mayer, at Mayer Chiropractic, which celebrated its 60th anniversary in February 2018. In 2000, Dr. Hunt completed her Diplomate in Clinical Chiropractic Pediatrics (DICCP), becoming the first board-certified pediatric chiropractor in Florida. In 2013, Dr. Hunt was appointed to the Florida Board of Chiropractic Medicine by the Governor and continues to serve on that board today. In 2016, Dr. Hunt was awarded her Fellow in Craniocervical Junction Procedures (FCCJP). Dr. Hunt has presented at seminars and conferences concerning upper cervical care across North America and in Europe for the ICPA, the ICA, Society of Orthospinology, The Florida Chiropractic Society, Academy of Upper Cervical Chiropractic Organizations, and many other Upper Cervical and State organizations.

In 2000, Dr. Hunt completed her Diplomate in Clinical Chiropractic Pediatrics (DICCP), becoming the first board-certified pediatric chiropractor in Florida. In 2013, Dr. Hunt was appointed to the Florida Board of Chiropractic Medicine by the Governor and continues to serve on that board today. In 2016, Dr. Hunt was awarded her Fellow in Craniocervical Junction Procedures (FCCJP). Dr. Hunt has presented at seminars and conferences concerning upper cervical care across North America and in Europe for the ICPA, the ICA, Society of Orthospinology, The Florida Chiropractic Society, Academy of Upper Cervical Chiropractic Organizations, and many other Upper Cervical and State organizations.

Dr. Hunt has published several papers in a peer-reviewed journals and is a contributor to several chiropractic textbooks.