|

![]()

From the Townsend Letter |

||||

Small Intestine Bacterial Overgrowth: Often-Ignored Cause of Irritable Bowel Syndrome by Allison Siebecker, ND, MSOM, LAc, and Steven Sandberg-Lewis, ND, DHANP |

||||

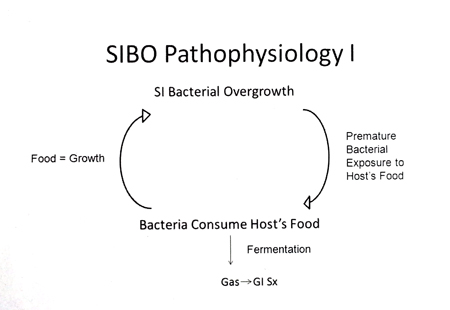

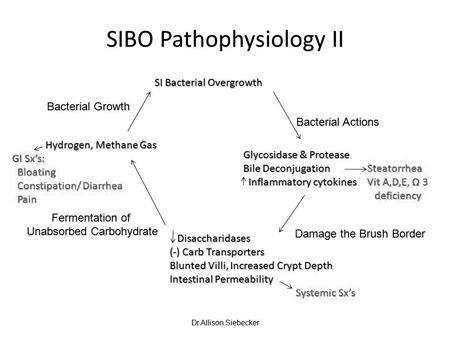

FIRST PLACE WINNER! Our experience has been that naturopathic approaches to irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) tend to be highly successful. Often, uncovering and removing hidden food intolerances, adding mindfulness to a rushed approach to meals, or restoring production of digestive acid or enzymes is the key to resolving IBS. But what about those cases in which bloating, abdominal pain, constipation, or diarrhea remain unchanged? After more life-threatening diagnoses are ruled out, where do you turn? Small intestine bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) is a condition in which abnormally large numbers of commensal bacteria are present in the small intestine. SIBO is a common cause of IBS – in fact it is involved in over half the cases of IBS and as high as 84% in one study using breath testing as the diagnostic marker.1,2 It accounts for 37% of cases wherein endoscopic cultures of aerobic bacteria are used for diagnosis.3 Eradication of this overgrowth leads to a 75% reduction in IBS symptoms.4 Bacterial overgrowth leads to impairment of digestion and absorption and produces excess quantities of hydrogen and/or methane gas. These gases are not produced by human cells but are the metabolic product of fermentation of carbohydrates by intestinal bacteria. When commensal bacteria (oral, small intestine or large intestine) multiply in the small intestine to the point of overgrowth, IBS is likely. Hydrogen/methane breath testing is the most widely used method of testing for this overgrowth. Stool testing has no value in diagnosing SIBO.

Other diseases associated with SIBO include hypothyroidism, lactose intolerance, Crohn's disease, systemic sclerosis, celiac disease, chronic pancreatitis, diabetes with autonomic neuropathy, fibromyalgia and chronic regional pain syndrome, hepatic encephalopathy, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, interstitial cystitis, restless leg syndrome, and acne rosacea.5–17 Other diseases associated with SIBO include hypothyroidism, lactose intolerance, Crohn's disease, systemic sclerosis, celiac disease, chronic pancreatitis, diabetes with autonomic neuropathy, fibromyalgia and chronic regional pain syndrome, hepatic encephalopathy, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, interstitial cystitis, restless leg syndrome, and acne rosacea.5–17

Mechanisms by which Overgrowth is Prevented Definition How SIBO Causes the Symptoms Of IBS Figure 1

Second, bacteria damage the digestive and absorptive structure and function of the small intestine. This occurs because, unlike the large intestine, the small intestine is not designed for large colonization. The damage leads to both gastrointestinal and systemic symptoms (Figure 2). Key damaging factors are: bacterial deconjugation of bile, which creates fat malabsorption (steatorrhea, fat-soluble vitamin deficiency); bacterial digestion of disaccharide enzymes, which furthers carbohydrate malabsorption, fermentation, and gas; and increased intestinal permeability (leaky gut), which leads to systemic symptoms.34–38 Figure 2

Diagnosis of SIBO Preparation for the test varies from lab to lab, but a typical prep diet is limited to white rice, fish/poultry/meat, eggs, clear beef or chicken broth (not bone broth or bouillon), oil, salt, and pepper. The purpose of the prep diet is to get a clear reaction to the test solution by reducing fermentable foods the day before. In some cases, two days of prep diet may be needed to reduce baseline gases to negative. Antibiotics should not be used for at least 2 weeks prior to an initial test; some sources recommend 4 weeks.39

We have found that an absolute level of gases at or above the positive ppm levels provided by Quin Tron, without a rise over baseline, correlates well with clinical SIBO. This is especially true for methane gas, which can have a pattern of elevated baseline (over 12 ppm) which remains elevated for the duration of the test. In cases such as these, methane may only rise 5 ppm over baseline, but the ppm level is consistently above positive. Interpretation of elevated hydrogen or methane on the baseline specimen (pre-lactulose ingestion) is controversial, but we prefer to consider a high baseline to be a positive test.31,40

|

||||

![]()

Consult your doctor before using any of the treatments found within this site.

![]()

Subscriptions are available for Townsend Letter, the Examiner of Alternative Medicine magazine, which is published 10 times each year.

Search our pre-2001 archives for further information. Older issues of the printed magazine are also indexed for your convenience. 1983-2001 indices ; recent indices

Once you find the magazines you'd like to order, please use our convenient form, e-mail subscriptions@townsendletter.com, or call 360.385.6021 (PST).

360.385.6021

Fax: 360.385.0699

info@townsendletter.com

Who are

we? | New articles | Featured

topics | e-Edition |

Tables of contents | Subscriptions | Contact

us | Links | Classifieds | Advertise |

Alternative

Medicine Conference Calendar | Search site | Archives |

EDTA Chelation Therapy | Home

© 1983-2013 Townsend Letter

All rights reserved.

Website by Sandy

Hershelman Designs